If the debate in today's Republican Party over how to address the deficit feels a bit one-note, it's because it is. When it comes to members of Congress, John Boehner's oft-repeated line that "We don't have a revenue problem; we have a spending problem" is the rule among Republicans (with a few notable exceptions). And when it comes to the party's presidential candidates, it's a universally held conviction. There is very little disagreement: Deficits are one of the chief threats to America -- but they can never be tackled by raising taxes; in fact, taxes must be lowered.

The prevalence of this contradictory posture in the GOP is a relatively recent phenomenon. And while the story of how it has taken hold is long and involved, it can be argued that there are really two critical turning points in the modern era.

The first came in 1980, when Republicans staged a presidential primary campaign that -- by today's standards -- was remarkable for its ideological diversity. It boiled down to a two-way race between Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush.

The fault lines were clear and well-defined. Reagan represented the rising Goldwater wing of the GOP -- fiercely anti-tax and anti-government, staunchly anti-Communist, and far to the right on cultural issues. In this wing of the GOP, a new economic theory offered by Arthur Laffer was taking hold: that slashing income tax rates would actually lead to higher government revenues, with lower taxes spurring economic growth and increasing Americans' taxable income. In Congress, Sen. William Roth of Delaware and Rep. Jack Kemp of New York proposed radical tax relief legislation in the late '70s, and Reagan embraced the effort in his campaign.

On the other side of the GOP ideological spectrum was Bush, representative of the "town father" wing of the GOP -- pragmatists who saw a meaningful role for government in Americans' daily lives but who were wary of bureaucracy and who saw evil in red ink. Bush separated himself from Reagan on numerous issues (for instance, Bush expressed support for the Equal Rights Amendment and for abortion rights -- both of which Reagan and the New Right fiercely opposed). But the biggest difference between them was on basic economic philosophy. To Bush and his ilk, Laffer's theories were utter nonsense and a recipe for fiscal disaster.

"This program of a tax cut may be good politics in the short run because we are so overtaxed," Bush said of Reagan's plan. "But it would be a disaster in human and economic terms."

In another speech, Bush declared: "It is impossible for Gov. Reagan to balance the budget -- an essential component of bringing down inflation -- if he is to reduce taxes by more than $220 billion over the next three years."

And in a line that haunted him for years to come, Bush told a crowd in Pittsburgh in April 1980, that Reagan was proposing "a voodoo economic policy" that couldn't work.

From today's vantage point, it's somewhat amazing to consider how well Bush did in the '80 primaries. He'd entered the race with virtually no name recognition (a former CIA director, U.N. ambassador, Republican National Committee chairman, and two-term congressman), little money and no organization. Reagan, meanwhile, had come agonizingly close to stealing the 1976 nomination from Gerald Ford -- and entered the '80 contest as the clear favorite. And yet, Bush managed to stun Reagan in the Iowa caucuses and -- very briefly -- appeared poised to repeat the feat in New Hampshire (where Reagan was saved in part by some memorable theatrics). Even after that, Bush still went on to post another upset in Pennsylvania before fading for good. His performance was so strong, in fact, that Reagan -- who had wanted to put a fellow true believer (perhaps Kemp) on the ticket -- was compelled to offer him the No. 2 slot.

But while Bush's showing was impressive, what really mattered was that Reagan and his fellow Laffer adherents had won. Within seven months of taking office, Reagan pushed through Congress and signed into law a massive reduction of tax rates. Supply-side economics was no longer just a theory; it was now the official doctrine of the Republican Party -- and the official policy of the United States. In the nearly 200 years before Reagan took office, the country had racked up a total of about $1 trillion in debt. By the end of his two terms, that number had nearly tripled. It was during the Reagan years that conservatives learned to rationalize massive deficits.

Of course, the old Laffer-resistant wing of the GOP didn't disappear all at once. Party loyalty (and the scope of Reagan's '80 landslide) persuaded most of them to go along with the new president's economic program in 1981, but much of the old skepticism -- and distaste for deficits -- remained. This was true even when it came to Bush.

As vice president, he was unfailingly loyal to Reagan, publicly backing all of his policies, no matter how strenuously he'd opposed them as a candidate. It was for a purpose: If he wanted to win the top job for himself in 1988, Bush realized, he would need at least some of the Reaganites to be with him.

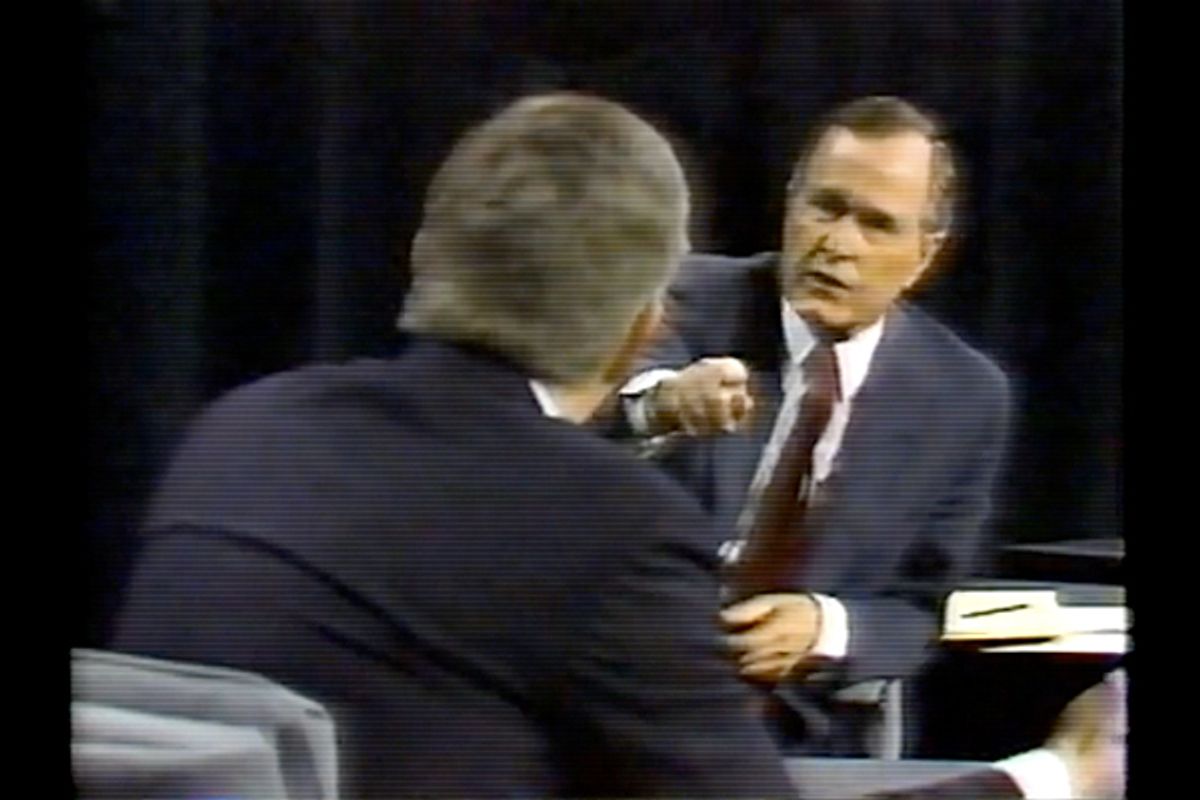

But even then, there were still glimpses of the old "town father." For instance, in the '88 GOP race, Bush was opposed by (among others) Kemp, who touted himself as Reagan's true ideological heir -- and who declared that the Reagan Revolution would be "over, gone, dead" if Bush ever claimed the Oval Office for himself. Bush, for his part, ran on a pledge not to raise taxes, and fended off another rival -- an old Laffer skeptic named Bob Dole -- with charges that he was too soft on taxes. But Bush also resisted Kemp's calls for further dramatic tax cuts, on the grounds that they'd make the country's ballooning deficits even worse. Here, for instance, was their exchange during one of the final '88 GOP debates:

Bush ended up winning the nomination with relative ease (after an early scare in Iowa) -- and further won over the Reagan crowd with his acceptance speech at the GOP convention, in which he promised to fight any effort from Democrats in Congress to raise taxes with words he would live to regret:

It took Bush until the fall of 1990 to go back on that promise. In a way, his decision to strike a tax hike deal with Congress was entirely consistent with his pre-1980 philosophy. The debt was now over $3 trillion (and rising) and revenues were slowing, thanks to a weakening economy. For the man who had shown his true colors when he'd lectured Jack Kemp about the evils of deficits, there was only one responsible choice. The deal Bush cut with leaders in Congress (including Dole, then the Senate's top Republican, and Robert Michel, the House minority leader) created a new 31 percent tax bracket, raised the gas tax, and ended a number of deductions. The goal was deficit reduction.

But Bush faced a revolt from his own party, led by a rising House Republican star -- Newt Gingrich. One hundred and twenty-six of 173 House Republicans ended up voting against the plan, as did 24 of 43 Republicans in the Senate. The roll call tallies revealed how much the Reagan wing had grown -- and how significantly the Bush wing had shrunk -- since 1980.

In many ways, that 1990 budget vote was the last hurrah for the pre-Reagan crowd. When the economy seemed to worsen in 1991 and 1992, the right took it as proof of the poisonous effects of raising taxes. In fact, the early '90s recession actually began before the tax hikes were passed and put into effect and it technically ended in June 1991 (even if unemployment and economic anxiety remained high through 1992). But the right was in no mood to hear this, and the remaining Laffer skeptics in the GOP quickly concluded that it was in their political interest to play along. Thus, when Bill Clinton came to power in 1993 and proposed further tax hikes to fight the deficit, every single Republican in Congress stood against him. And when Dole grabbed the GOP nomination in 1996, he turned for a running mate to Jack Kemp -- and, junking years of resistance to supply-side theory, ran in the fall on a pledge to cut taxes 15 percent across the board. (That the Bush and Clinton tax increases actually produced record surpluses by the end of the decade had no measurable effect on GOP economic philosophy.)

Dole got the message back then, and just about every ambitious Republican since then has, too: Republicans like to talk about how bad deficits are -- but they're not nearly as important as tax cuts.

Shares