For the first time in eight weeks, the price of gasoline in the United States is falling. Not by much -- only half a cent a gallon over the past week -- but any relief at the pump is welcome after this year's seemingly inexorable rise. Not uncoincidentally, the price of oil fell below $97 a barrel on Tuesday, continuing a sustained drop from its most recent high of $115 on May 2.

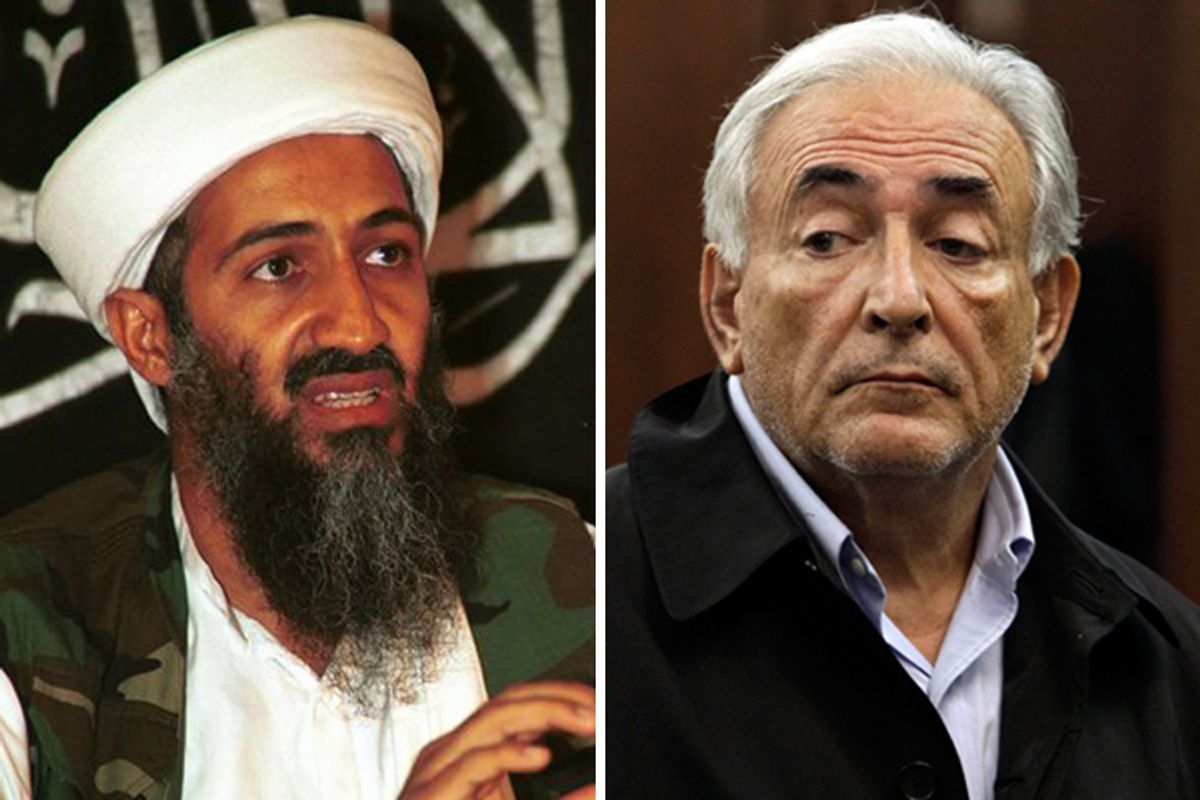

On May 1, President Obama announced to a stunned world that a team of Navy Seals had killed Osama bin Laden. Within 24 hours, market analysts were wondering what effect the death of the world's most famous terrorist would have on the price of oil. Some speculated that reprisal attacks in the MidEast might further destabilize the region and push prices up. Others suggested exactly the opposite -- that the world might take bin Laden's death as a sign that geopolitical tensions could ratchet down -- and in consequence, oil prices would fall.

A week after bin Laden's death, after a sharp, historically unprecedented plummet in the price of oil, the temptation to connect energy prices with the events in Abbottabad became even more irresistible.

The political risk premium built into oil prices also came under scrutiny last week. The unrest sweeping through the Arab world -- home to over half of world oil reserves -- has boosted oil this year....

"We've been in a world thinking there's more risk, more risk, more risk," said Sarah Emerson of Energy Security Analysis Inc. "People took this week, and the news of bin Laden's death, to simply reflect. They stopped and said, maybe there's less risk."

Perception, here, trumps reality. It is far too soon to tell whether the world is actually "safer" in any meaningful way after bin Laden's death. But if traders in oil futures feel that the world might be a little less risky, it doesn't take much to pop the speculative balloon. A little bit of selling can create a lot of momentum in the opposite direction.

Maybe. The drop in oil prices could just as easily be a response to growing fears of an economic slowdown in the U.S. and China. Or it might just be a temporary respite -- demand for oil, worldwide, is still on the upswing, while supply is constrained, and that's a recipe for sustained long-term price hikes. But there is at least a possibility of real causation in this case. Osama bin Laden was killed, oil prices immediately started dropping fast, and now, gas prices are falling as well. And if gas prices continue to drop, President Obama's fortunes are likely to rise. Few things seem to bum Americans out more than getting gouged at the gas pump on a regular basis. By Election Day 2012, voters may have forgotten that Obama killed Osama, but if gas prices keep falling, or at least stop rising, that alone could be enough to reward the incumbent with another term.

Now let's turn to the case of Dominique Strauss-Kahn. Over the past year and a half we've followed endless speculation as to the question of how Europe's ongoing sovereign debt crisis will be resolved. Could the European Union just muddle its way through, keeping everything stitched together with spit and duct tape, or will countries like Greece and Portugal and Ireland ultimately end up defaulting on their debt, potentially destabilizing the European banking system and disrupting global economic growth? Or even worse, might they decide to opt out of the euro altogether? The variables at play are numerous and hard to compute, but until this week, I don't think anyone could have imagined that the arrest of the head of the IMF in New York on sexual assault charges might turn out to be a determining factor in how the future of European economic integration plays out.

But that seems to be exactly the case. Thewringing of hands in Europe over the past 24 hours has been extraordinary. Strauss-Kahn seems to be the only man in Europe trusted by both the leaders of Germany and Greece.

The Financial Times' Martin Wolf:

Mr Strauss-Kahn was among the very few senior European policymakers to whom the German leadership, particularly Angela Merkel, the chancellor, paid attention. At crucial moments, he was able to bring Europeans together. Indeed, he even seemed able to bring a divided German government together. I cannot imagine who could replace him. When there exist so many divisions within Europe and the decisions ahead are so complex and fraught, his absence will be keenly felt.

He supported the view, also held by the European Central Bank, that a eurozone member should not rush into default. The eurozone clearly needed the IMF's technical competences in dealing with its sovereign debt crises -- a set of skills largely absent in the European institutions. It also needed the IMF's co-financing. But the IMF's single most important influence in eurozone crisis resolution has been political. In a situation marked by a lack of political leadership, the IMF filled a vacuum.

At this juncture, the consequences of Strauss-Kahn's fall from grace are impossible to predict; the first preliminary forecasting efforts are already dissolving into contradiction . Just moments ago, two pieces of economic punditry popped up on my blog reader: Time's Roya Wolverson wondered "Will Strauss-Khan's Fall Lead to the Dollar's Demise?" while The Atlantic's Megan McArdle asked "Is the Downfall of Dominique Strauss-Kahn Also the Downfall of the Euro?" One or the other might prove true, but it's hard to imagine a scenario in which both the dollar and the euro are battered by Strauss-Kahn's removal from the scene.

What's undeniable is that there will be some kind of consequence, even if we have no idea what is. The course of European history has already been altered, for reasons that are remarkably surreal. A butterfly flapped its wings in a New York luxury hotel suite, and the fate of entire nations is suddenly in play.

The lesson? We should never underestimate the contingent nature of history. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, we've seen countless heated debates over how the financial sector should be regulated, or what government levers should be pulled to properly manage the economy. What's the right fiscal and monetary policy? More Keynesian stimulus or the tough medicine of austerity? Should Europe's ailing nations be bailed out or forced to suffer? And yet in the middle of all this clamor, all these effort by humans to act with agency upon the world, all too often the catalyst for change turns out to be a random byproduct of some event that was never plugged into any economist's model. The death of Osama bin Laden and the disgrace of Dominique Strauss-Kahn have removed some powerful pieces from the global chessboard, and reminded us, once again, that we're all just winging it, on this planet.

Shares