Every week, the Peabody Award-winning public radio program "On the Media" takes an essential but maddeningly immaterial subject -- how journalism, entertainment, advertising and other communications work -- and makes it graspable, urgent and wryly amusing. Much of the credit for this remarkable transubstantiation goes to longtime producer and co-host Brooke Gladstone, who consistently strikes the right balance between knowingness and idealism. She's all too aware of how the media really functions, but she never loses sight what the public wishes and imagines it to be.

Because there's such a gap between our dream (or nightmare) of the media and the reality, this gig requires a highly developed sense of irony. Say you're doing a story (as Gladstone did last fall) about the fact that the press will come down harder on a politician who lies about himself than on a candidate who lies about his opponent, and that it's much easier to get away with misrepresenting policy than with fibbing about personal matters. As a result, slandering your opponent's position on healthcare reform causes less of a fuss than claiming you dodged sniper fire on a diplomatic mission to Bosnia when you didn't.

Interviewing the analyst who made these observations (Paul Waldman of the American Prospect), Gladstone summarized one of his explanations thus: "The media have less expertise to evaluate a policy charge, and anyone is an expert when it comes to personal matters." When Waldman argued that reporters should instead pay closer attention to the veracity of claims that directly pertain to what the candidate might do in office, Gladstone remarked, "You're asking them to focus on the relevant" -- in a tone that was tantamount to a raised eyebrow. Then both of them laughed, because there are times when you have to laugh to keep from weeping or screaming.

This isn't a sensibility that translates easily to print, but Gladstone has nailed it by opting for a comic-book format for her first book, "The Influencing Machine"; the images work as a puckish counterpoint to occasionally abstract discussions, as well as sobering reminders of the real-world consequences of the media's misdeeds. Originally announced as a "manifesto," the book is nothing so strident as that label implies. Instead, it's a synthesis of what Gladstone has learned in editing several NPR news shows, covering Russia during the mid-1990s and, above all, working on "On the Media."

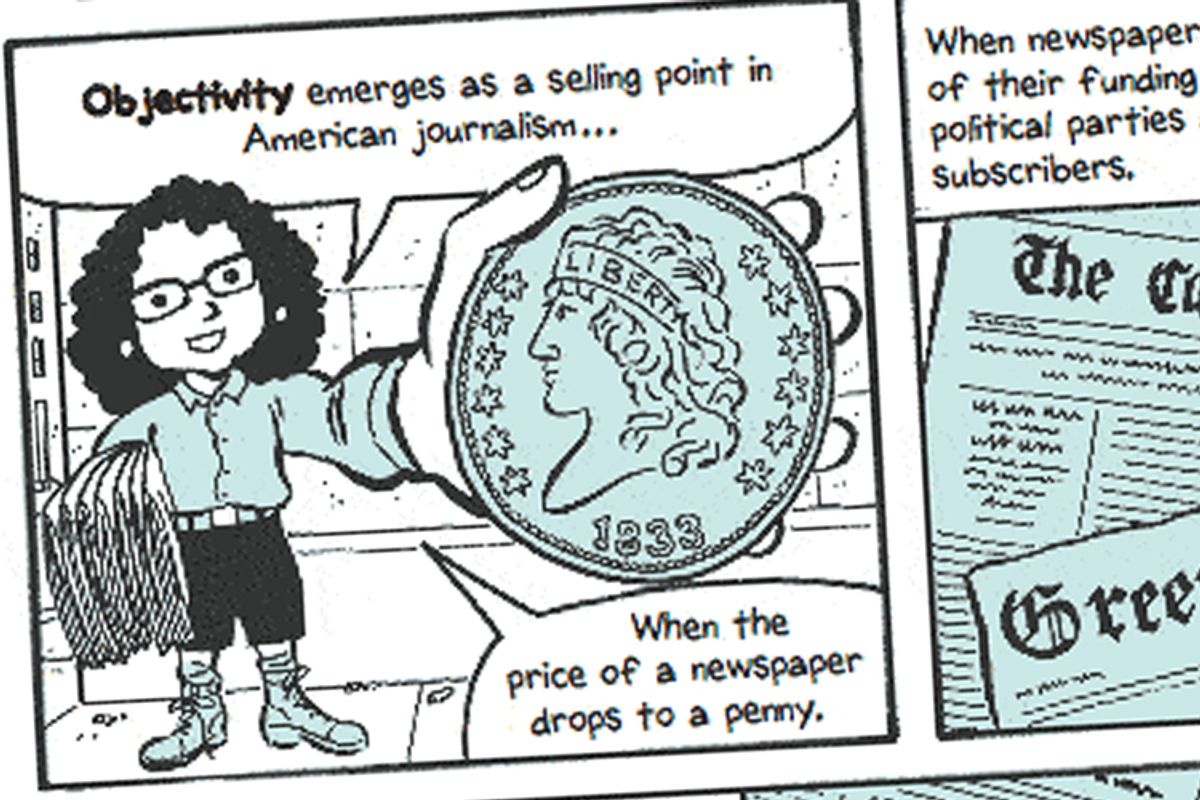

Modeled on Scott McCloud's classic primer "Understanding Comics," "The Influencing Machine" visits such persistent concerns as freedom of speech, sensationalism, groupthink, information overload and, of course, objectivity and bias. In panels drawn by Josh Neufeld, a cartoon version of Gladstone strides through an ever-shifting series of backdrops (the American Revolution, the Red Scare, Vietnam) used to illustrate this or that important point. In her trademark nerd specs and cloud of black hair, she appears among the damned in Dante's Inferno (illustrating the belief that journalistic neutrality is a moral cop-out), as the statue of Saddam Hussein being pulled down in al-Firdos Square (showing how journalists make events appear more dramatic than they really are) and as the Bride of Frankenstein with an "Intel Inside" sticker on her forehead (representing the future of communications technology in -- gulp! -- brain implants).

It's hard for anyone who works in the media to judge how revelatory "The Influencing Machine" will seem to civilians. Journalists take it for granted that there is no piece of reporting so judicious that someone won't accuse it of bias, just as there's no story so slanted that someone else won't commend it for its fairness. The job involves juggling an insanely complex set of internal and external checks and balances and never getting it just right. But every reader will surely benefit from the chapter titled "The Matrix in Me," in which Gladstone reviews the overwhelming evidence that decisions most of us believe to be perfectly rational are primarily governed by unconscious responses and undetected prejudices. The human mind is frighteningly easy to sway, and consumers of media need to be just as vigilant against their own biases as those who produce it.

The fundamental argument of "The Influencing Machine" is that the media and the public are far more intertwined and mutually implicated that the public chooses to acknowledge. The book's title comes from a delusion common in schizophrenics that some terrible outside entity is forcing shameful, unbidden thoughts into their heads when in fact those thoughts originate in their own minds. "The media don't control you," Gladstone writes. "They pander to you." Until we're willing to fess up to our own complicity, and to wrestle with the "neural impulses that animate our lizard brains," we will go on getting nothing better than "the media we deserve."

Shares