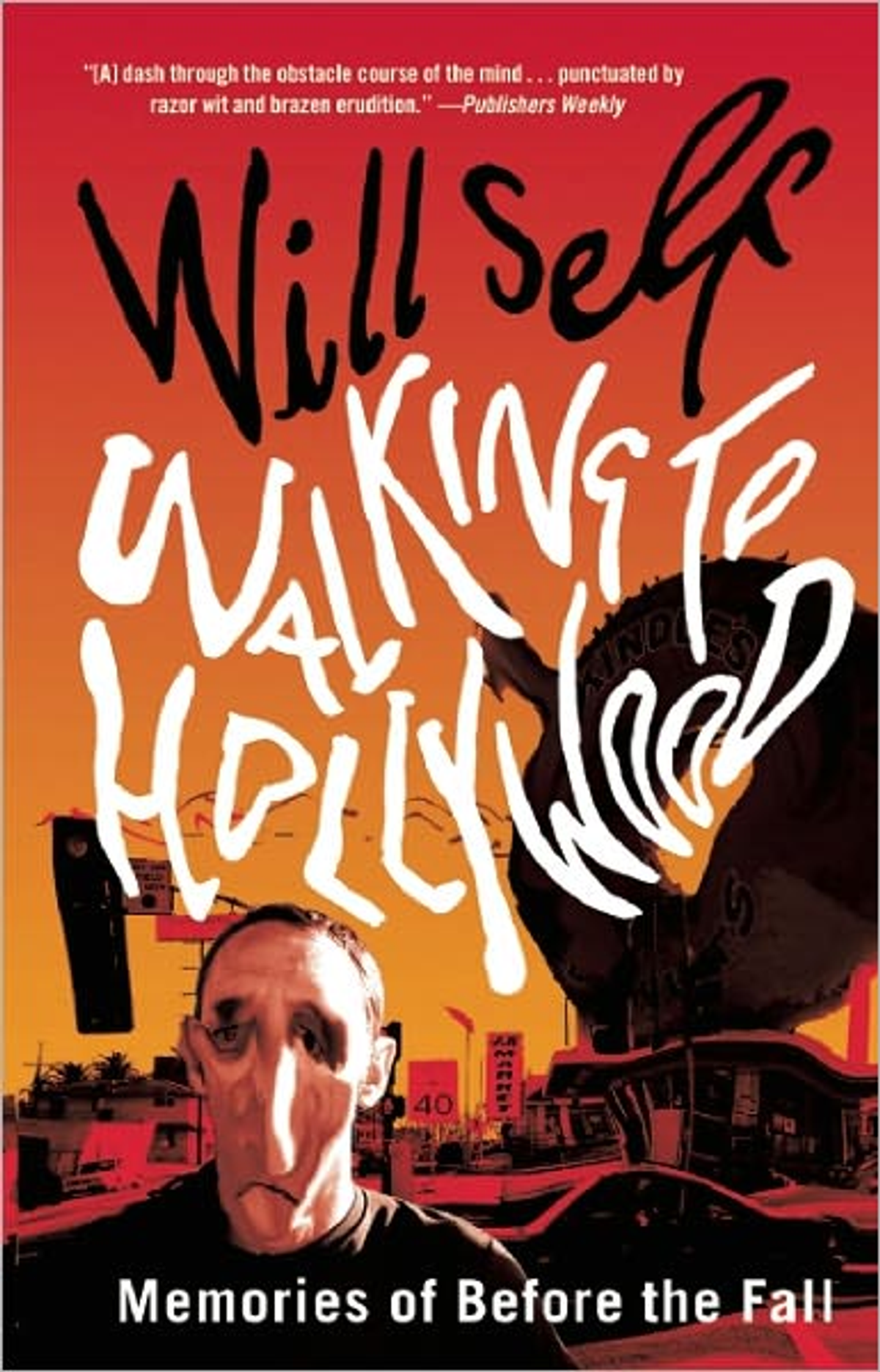

If neorealist gloom-puss Michelangelo Antonioni had directed "Who Framed Roger Rabbit," from a script by J. G. Ballard, S. J. Perelman, and Jean Baudrillard, starring Scooby Doo, the Marx Brothers, Laura Harring, and the ghost of Orson Welles, the result might very well have approximated Will Self's latest offering, "Walking to Hollywood," which the author bills in a footnote as an "implausibly reconstructed memoir." (Readers seeking something similar are well advised to try Rudy Rucker's "Saucer Wisdom.")

Am I committing an outrageous cinematic comparison here? A preposterous, lunatic metaphor strained beyond belief? Excellent, then! My crime proves I am fully in tune with Self's gnomic, gnostic Grand Guignol. Surreal, scurrilous, solipsistic, sarcastic, and sardonic, Self's newest bit of unclassifiable literature continues his career-long carpet-bombing of contemporary culture's most heinous aspects, sparing no one, including the author himself.

Am I committing an outrageous cinematic comparison here? A preposterous, lunatic metaphor strained beyond belief? Excellent, then! My crime proves I am fully in tune with Self's gnomic, gnostic Grand Guignol. Surreal, scurrilous, solipsistic, sarcastic, and sardonic, Self's newest bit of unclassifiable literature continues his career-long carpet-bombing of contemporary culture's most heinous aspects, sparing no one, including the author himself.

I first read Self nearly 20 years ago, with the appearance of his debut, "Cock and Bull." Its two novellas, both centering around aberrant human somatypes, to phrase the matter delicately, displayed a vivid visual imagination; a reckless take-no-prisoners, Seal Team 6 approach to narrative; and a chilly, fleering assessment of the human condition. Imagine a British Michel Houellebecq, yet not frigid and remote: a quintessentially Anglo jester possessed of a rubber chicken filled with bile and a squirting lapel flower charged with cat pee.

Self set out as he meant to continue, and in subsequent novels and stories, whether dealing with simian role reversal ("Great Apes") or the banality of the afterlife ("How the Dead Live") or the allure of drugs ("The Rock of Crack as Big as the Ritz"), the author magnificently expanded his range, plotting, verbal dexterity, and list of targets, while retaining his essential attitude and message. Life is a mug's game, leavened infrequently by small redemptive moments. The mass of mankind are brutish, self-centered trolls, prone to trampling upon the sensitive few. The best of us are self-deluded, the worst self-righteous. A dry, cutting wit and a studied indifference to cruel fate are the best defenses against the malignity of the cosmos.

Needless to say, a receptive reader has to align himself at least partially with this Weltanschauung to relish Self's fiction. You cannot appreciate one of his books if you are going in expecting Toni Morrison, Margaret Atwood, or even Salman Rushdie -- three writers in fact who take a brutal drubbing in "Walking to Hollywood." But assuming you are the sort of reader who thinks that Twain's "Letters From the Earth" and Ben Hecht's "Fantazius Mallare" should be a mandatory part of the curriculum in primary schools across the nation, then you will certainly chortle with pleasure and wince with recognition at the exploits of "Will Self" in "Hollywood."

This tripartite book is, as Self comments in a brief afterword, a magical mystery tour across the psycho-spatial terrain of three pathologies: obsessive-compulsive disorder for "Very Little," psychosis for "Walking to Hollywood," and Alzheimer's for "Spurn Head." The tenuously but provocatively interrelated adventures all revolve around a shape-shifting protagonist who shares much of Self's biography and CV.

"Very Little" chronicles the career of Sherman Oaks, dwarf and world-famous sculptor, whose sole theme is his own distorted body, writ large in massive public monuments. Oaks' obsession with aggrandizement and self-promotion can be seen as emblematic of the megalomaniacal paradigm inflicted upon creators in this postmodern age, where a steady stream of tweets and Facebook posts are necessary to confirm one's worth and inform the world at large of one's irreplaceable genius. Boyhood chums, Oaks and Self have entered middle age as demanding monster and dubious acolyte. But in Los Angeles, as Self begins to undergo mental deterioration, Oaks' unwavering confidence and ego durability serve as a life preserver -- until the artist himself evaporates in a manner reminiscent of Tyrone Slothrop's in "Gravity's Rainbow."

This occurrence triggers the next installment, the generous meat of the narrative sandwich, "Walking to Hollywood." We begin again in London, as Self consults with his loony psychiatrist, Dr. Zack Busner, before voyaging to California, where his various neuroses and delusional behaviors will have free rein to exfoliate in a Lewis Carroll wonderland. Self swaps identities with the actors "playing him" in an imaginary documentary about hiking through the L.A. urban landscape: David Thewlis and Pete Postlethwaite. Layered onto the documentary conceit is another, that Self is secretly conducting a noirish investigation into "who killed film."

This quest manifests itself hallucinatorily as every person Self meets, from clerk to bum, is secretly played by a famous actor. The writer's bizarre peregrinations across the blasted media landscape -- evoking the real-world long walks he has recounted in more sober journalistic essays -- eventually lead to an implosion of primal forces, blasting Self back to London -- where in an interview with his alternate mental health expert, Shiva Mukti, he dissembles and conceals his temporarily quiescent insanity.

Self's targets, especially in the middle section, are manifold and eclectic. With the Hollywood theme of course come many potshots at inane actors, directors, studios, producers, scripters, and moviegoers. To some degree, this is like shooting neon tetra in a martini glass. There remains little fresh to satirize in the already hyperbolic cinematic milieu since, perhaps, the heyday of Nathanael West. As mentioned, Self also works over his fellow pretentious litterateurs pretty savagely. Toni Morrison and Salman Rushdie turn up as filthy, indigent street people, while Margaret Atwood comes in for some ribald off-color fantasies relating to her silly remote-autographing invention, "the Long Pen."

Self's Los Angeles is saturated with science fiction. His reality-tripping echoes Philip K. Dick, of course, and "Blade Runner" is specifically invoked. He reserves his most savage loathing for SF theocratic scammer L. Ron Hubbard and the Scientologists. A scene of Self and L. Ron dancing an aerial pas de deux before a worshipful audience is merely the start of the mockery.

But the object of Self's most savage barbs is always himself. "You were a spotty brat jerking off over Ornella Mutti in the London burbs. Then you grew up and began writing your dismal [expletive deleted] tales -- a depressive's exercise in wish fulfillment." At the seaside in the final chapter, Self confronts the carcass of a dead seal. "All the anger and the nihilism, all the alienation and disgust, all the friendships neglected and lovers abandoned, all the children abused and neglected, all the trans-generational misery of a row that had continued decade upon decade, sustained by senseless bickering, all the oily repulsion that kept me from them was crammed into the gap between my palms and the pup's flanks." It's a moment of sour satori -- Self keeps a Buddhist motif going throughout -- that harks back to William Burroughs' explanation for his phrase "naked lunch": "a frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork."

Only an unflinching and wild-eyed vivisectionist of our dead souls such as Will Self could couch his coroner's report in such precise yet exotic language.

Shares