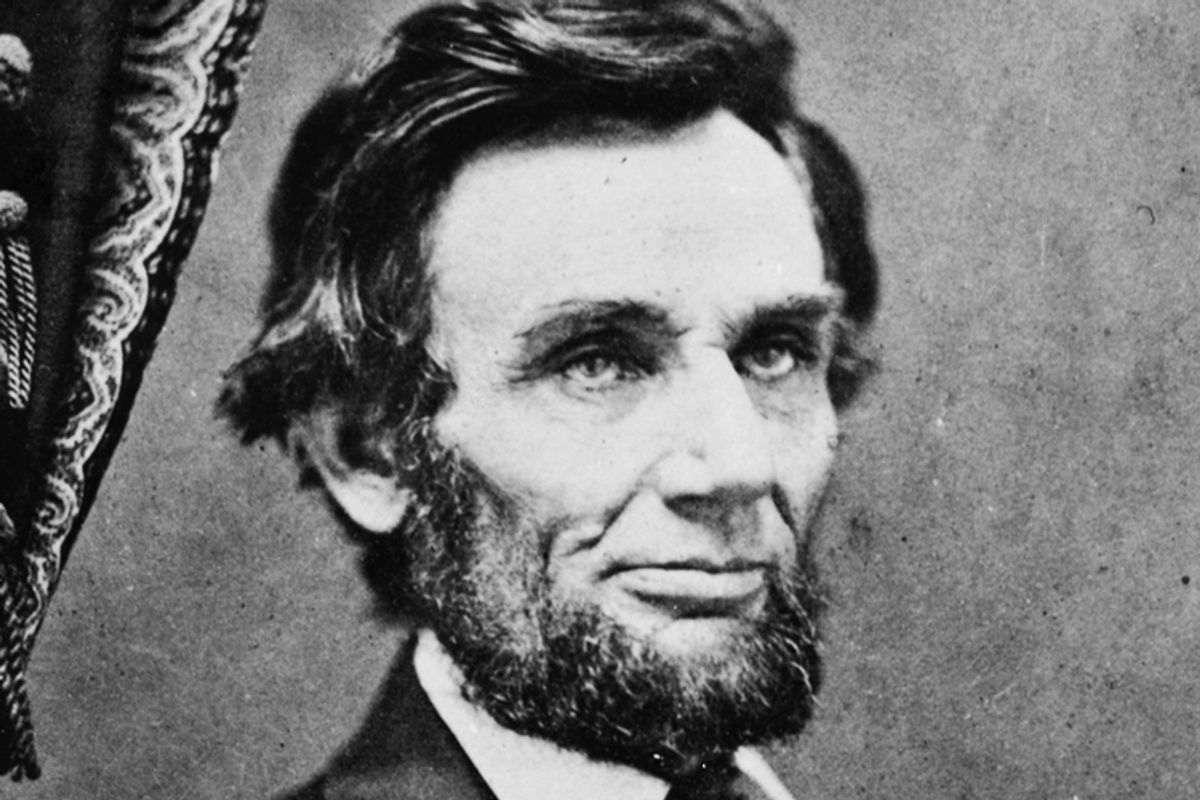

No face in American history is more recognizable than Abraham Lincoln's.

His lean, craggy, hollow appearance -- with tousled hair and scraggly beard (without a mustache) and melancholic eyes -- is known around the world. His profile appears on the penny, and an engraved portrait appears on the $5 bill. His image was included among the four presidents carved out of the cliff face of Mount Rushmore (although sculptor Gutzon Borglum and his work crew never finished all the intended features -- namely, a portion of a hand holding a lapel -- below Lincoln's face; Borglum died in 1941 and the onslaught of World War II diverted project funding elsewhere). The bicentennial in 2009 of Lincoln's birth occasioned the proliferation of Lincoln's face almost everywhere you looked (at least his home states of Kentucky and Illinois), even beyond the expected annual appearance of Lincoln to sell cars and mattresses during Presidents' Day sales every February. And we'll continue seeing a lot of Lincoln over the next four years as the commemoration of the Civil War sesquicentennial rolls along.

Historians have been fascinated by how dramatically Lincoln's face changed during his presidency. Photographs reveal how increasingly careworn he became over the four years during which he waged war against the Confederate States of America and struggled to restore the Union. One of his secretaries, John Hay, remarked that "under this frightful ordeal his demeanor and disposition changed -- so gradually that it would be impossible to say when the change began; but he was in mind, body, and nerves a very different man at the second inauguration [March 1865] from the one who had taken the oath in 1861. He continued always the same kindly, genial, and cordial spirit he had been at first; but the boisterous laughter became less frequent year by year; the eye grew veiled by constant mediation on momentous subjects; the air of reserve and detachment from his surroundings increased. He aged with great rapidity."

After his first inauguration in March 1861, William Howard Russell, an English journalist, described Lincoln's appearance at the start of his presidency. At this first meeting in the White House, Russell was less than impressed:

He entered [the room], with a shambling, loose, irregular, almost unsteady gait, a tall, lank, lean man, considerably over six feet in height, with stooping shoulders, long pendulous arms, terminating in hands of extraordinary dimensions, which, however, were far exceeded in proportion by his feet.

Russell reported that the president's neck was "sinewy muscular and yellow" and that his beard was "a great mass of hair, bristling and compact like a riff of mourning pins." Lincoln's face, he said, was "strange" and "quaint," and his head was topped "with its thatch of wild republican hair." Russell did not neglect to mention the president's "flapping and wide projecting ears" or his "penetrating" eyes, which he identified as "dark, full, and deeply set . . . but full of an expression which almost amounts to tenderness."

Not surprisingly, John Nicolay, another of Lincoln's secretaries, portrayed the 16th president with more sympathy and grandeur, explaining that artists had a particularly difficult time capturing Lincoln's "rugged features." In Nicolay's opinion:

Graphic art was powerless before a face that moved through a thousand delicate gradations of line and contour, light and shade, sparkle of the eye and curve of the lip, in the long gamut of expression from grave to gay, and back again from the rollicking jollity of laughter to that serious, far-away look that with prophetic intuitions beheld the awful panorama of war, and heard the cry of oppression and suffering.

Nicolay believed that "there are many pictures of Lincoln; there is no portrait of him."

Except there are 136 photographic poses or views of Lincoln (not counting long shots of him in the distance, such as those of him about to be seated after delivering the Gettysburg Address or standing at the East Portico of the Capitol as he delivered his second inaugural address), all of which do show us how he looked at various times of his life, from his days as a prosperous attorney in Springfield, Ill., during the 1840s to his last days as president in the spring of 1865.

It's true that even the photographs leave something lacking in our understanding of how Lincoln really looked: there is not a single photograph that shows him laughing (or that reveals his teeth), although some historians think they see the rudiments of a smile in at least one photograph (saying "cheese" for the camera did not become a convention until the early 20th century). Nicolay's comment about the "thousand delicate gradations" of Lincoln's face is probably well worth remembering; the existing photographs show a posed and practically frozen Lincoln, a necessity because photography at the time could not capture subjects in motion without becoming hopelessly blurred.

So we cannot know the animation of Lincoln's living face; the closest example might be Disneyland's Audio-Animatronics Lincoln, which, even with technological improvements that have been made since its debut 47 years ago at the Illinois Pavilion of the New York World's Fair, still remains too robotic to be credible. The numerous life-size silicone and latex mannequins at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Ill., look like Lincoln to a certain extent, but they are not animated, which is probably all for the best. What's more, color photography did not exist in the 1860s, so Lincoln's image -- apart from painted portraits -- survives only in black and white or, in a few instances, sepia tones. As a result, Lincoln remains forever a prisoner in a world of black and white, hidden to a degree by faded light and obtuse shadows. That's not necessarily a bad thing. It just means we have to use our imagination to conjure up the real Lincoln, the one who lived a colorful life in a colorful world.

In the end, we must rely on words combined with pictures to imagine Lincoln as he really was. His physical appearance, even during his youth, impressed nearly everyone he ever met. One neighbor in Indiana remembered the young Lincoln as "a long -- thin -- leggy -- gawky boy dried up & Shriveled." An Illinois man recalled Lincoln during the 1830s, when he lived in New Salem: "His eyes were a bluish brown, his face was long and very angular, when at ease had nothing in his appearance that was marked or Striking, but when enlivened in conversation or engaged in telling, or hearing some mirth-inspiring Story, his countenance would brighten up[,] the expression woul[d] light up not in a flash, but rapidly the muscles of his face would begin to contract. Several wrinkles would diverge from the inner corners of his eyes, and extend down and diagonally across his nose, his eyes would Sparkle, all terminating in an unrestrained Laugh in which every one present willing or unwilling were compelled to take part."

Lincoln often joked about his facial features, even acknowledging that to most people he looked rough and ugly. One story attributed to Lincoln involved him swearing to kill any man uglier than himself. Coming upon such a man one day, Lincoln aimed a gun at him, vowing to keep his promise. At first the man was shocked and frightened, but when Lincoln explained his purpose, the other man calmed down. "Sir," the man said to Lincoln, "you look as if you might put your threat into execution; but sir, all that I have got to say is, If I am any worse looking than you are, for God's sake shoot me and git me out of the way!" Lincoln, of course, held his fire. Another story about his homeliness involved his riding through the woods and encountering a woman, also on horseback, traveling toward him. The women reined in her horse and said: "Well, for land's sake, you are the homeliest man I ever saw." Lincoln agreed with her but said, "I can't help it." The woman replied: "No, I suppose not, but you might stay at home."

As president, though, the weight of the war bore down on him. Noah Brooks, a journalist, claimed that "few persons would recognize the hearty, blithesome, genial, and wiry Abraham Lincoln of earlier days" if they were to meet him again during his presidency. In the White House, Lincoln suffered from a "stooping figure, dull eyes, care-worn face, and languid frame." The president's "old, clear laugh," said Brooks, "never came back; the even temper was sometimes disturbed; and his natural charity for all was often turned into an unwonted suspicion of the motives of men." Visitors to the White House repeatedly reported how sad Lincoln looked. David R. Locke, better known as the humorist Petroleum V. Nasby, described Lincoln's deep and visible gloom: "I never saw a more thoughtful face, I never saw a more dignified face, I never saw so sad a face."

Walt Whitman, who spent part of the war working in the Union hospitals in Washington, saw Lincoln often in the wartime city. After the war, Whitman declared that despite the "hundreds of portraits [that] have been made, by painters and photographers . . . I have never seen one yet that in my opinion deserved to be called a perfectly good likeness; nor do I believe there is really such a one in existence."

Even so, the slide show that accompanies this piece reveals how Lincoln's appearance changed drastically from the time of his election in November 1860 to the spring of 1861, after the surrender of Fort Sumter and the start of the Civil War. As the slides show, the most notable change resulted from Lincoln's decision to grow a beard. No one is exactly sure why he became bearded in time to begin his presidency, although most men of prominence in the early 1860s sported facial hair, sometimes in a great profusion of whiskers down to their breastbones. Some New York Republicans believed that Lincoln would look more dignified, by which they meant less homely, if he wore "whiskers and ... standing collars." He may have added the beard so that he would be taken more seriously -- at age 51, he was one of the youngest presidents to date. Whatever the reason, the beard transformed Lincoln's face into the icon we most readily recognize today, although the slides demonstrate that his facial expressions and the cast of his eye could create subtle differences in his appearance.

How he looks in these slides reflect some of the limitations of photography at the time -- not only are these truly "still" pictures in the most precise meaning of the term, but field of depth and clarity were not hallmarks of Civil War-era photography, an art form that was still in its infancy. The wet-plate process relied on large glass plates immersed in a chemical solution that produced negative images that could be duplicated as positive images on paper. However, photographs could not be printed in newspapers or books because the half-tone, rotogravure technology would not come into being until two decades later. Nevertheless, images on paper, sometimes as stereographs that could be viewed through a stereoscope to create a three-dimensional effect, or sometimes on small cards known as cartes-de-visite, could be cheaply made and sold at modest prices. Many Northerners got to see Lincoln for the first time by seeing portrait photographs of him for sale in a local photographer's gallery; these prints were purchased by the thousands and displayed proudly in parlors throughout the Union. A portrait-size print could be bought for $1.50.

In the North, most people knew what Lincoln looked like by the end of the war. Or, at least, they thought they did. During this early age of photography, nearly everyone believed that the camera could not lie -- a belief now put to rest by Photoshop and other digital editing programs. Seeing is not necessarily believing. It also turns out that Civil War photographers, like the famous Mathew Brady and the less famous Alexander Gardner, regularly manipulated their subjects -- including individuals sitting for studio portraits -- more than anyone knew or understood at the time. These slides of Lincoln tell us a great deal about the man. They reveal, in fact, how his appearance changed over a relatively short span of time, sometimes blatantly (as with the addition of his beard), sometimes delicately (as with the cast of his eye). They show us how he attempted, in subtle ways, to control his public image with similar poses, his carefully chosen clothing, and even the tilt of his head. Here in these slides, in fact, are several different Lincolns, if you look close enough to find them. The man with the most recognizable face in American history turns out to have been a man of many masks.

Shares