Not long ago, nurse Theresa Brown wrote a provocative Op-Ed in the New York Times about the tension between nurses and doctors. "It's a time-honored tradition," one doctor sniped at her, "blame the nurse whenever anything goes wrong!"

Publicly airing this friction opened Brown up to sharp criticism. "Drawing and quartering your coworkers in the Sunday New York Times might be run-of-the-mill for politicians. I'd like to see something better out of doctors and nurses," wrote one physician over at the Atlantic. But don't count me among her detractors. Brown used her story to advocate for civility in medicine. Mutual respect, she correctly argued, would improve teamwork and the care of patients. Her essay raised a question far more important than who was right or wrong: If both nurses and doctors want to make their patients better, why is there so much conflict and controversy between them? And how do we do a better job of working together? To help me answer these questions, I asked Theresa Brown herself.

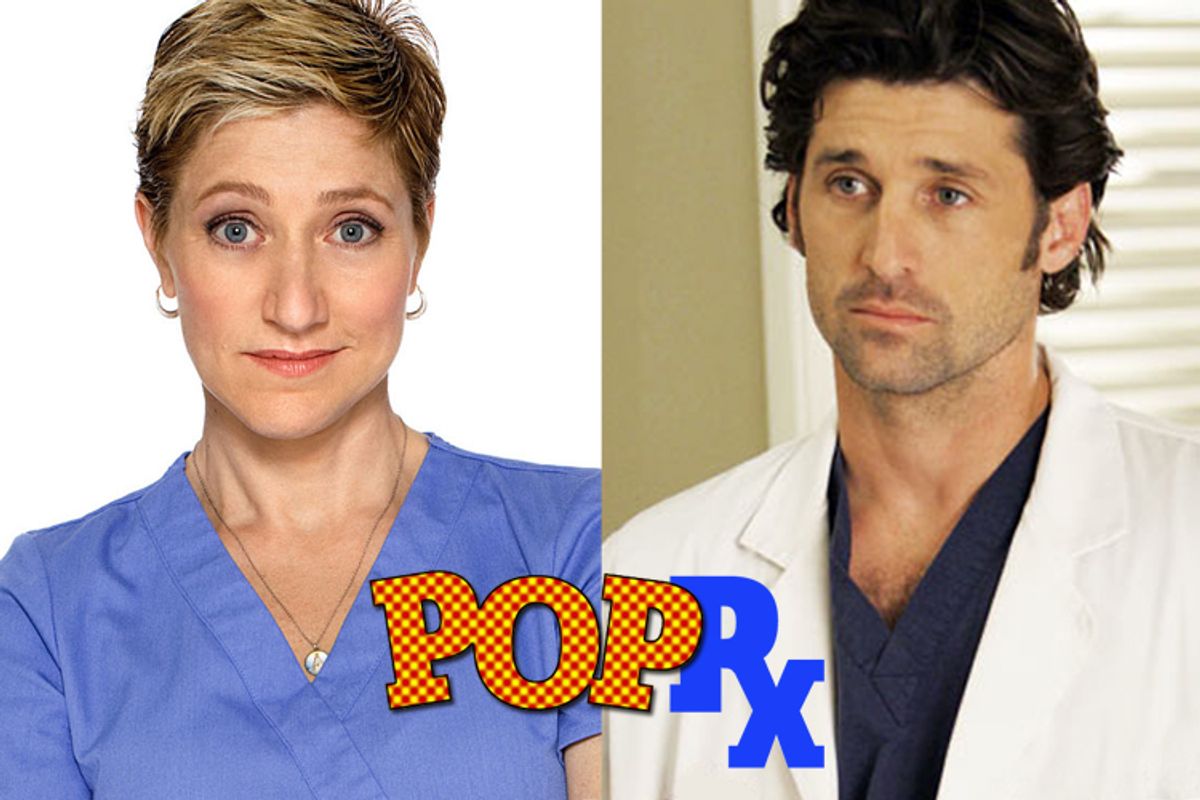

Before I get to that, it's useful to understand the cultural underpinnings of the doctor-nurse relationship. In one sense, nurses have spent the last half-century fighting to overcome the stereotype that they are defanged doctors. It's a division rooted in education, income and gender. Doctors -- men, affluent, with a professional education -- reigned supreme in the hospital. Nurses -- female, working-class, with a trade school-level education -- were their handmaidens. This stereotype is probably something you would expect to see on a vintage TV medical drama, though critics point out that it still is the norm on contemporary shows like "Grey's Anatomy."

Despite the rigidity of that power structure, nurses smartly honed their own skills of influence. This was best described in 1967 when a psychiatrist named Leonard Stein published an essay called "The Doctor-Nurse Game." "The nurse is to be bold, have initiative and be responsible for making significant recommendations, while at the same time be passive. This must be done in such a manner so as to make her recommendations appear to be initiated by a physician," Stein wrote. If a nurse didn't play well, she was "a bitch," or "unconsciously suffering from penis envy."

What changed between then and now? In 1990, Stein published "The Doctor-Nurse Game Revisited" to answer that question. The public lost confidence in doctors and medicine (something I've addressed before in this column). There was a rising demand for nurses, and the profession evolved into one with specialties (pediatric nurses, ICU nurses, etc).

That's the context in which I approached Brown. Why, despite all of these changes, does so much tension fester between doctors and nurses? Brown holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of Chicago and she also wrote the book "Critical Care: A New Nurse Faces Death, Life, and Everything in Between," recently out in paperback. As you might expect, she is articulate and smart. She is also warm and introspective and, despite what her critics say, does not have an ax to grind. She has written just as strongly about bad behavior between nurses.

Brown answered the question by talking about the way nursing education has changed. In the past, nursing schools were based in hospitals, which put students directly under doctors' influence. While that no doubt perpetuated the doctor-nurse game, at least it exposed both groups to each other. But over the past 40 or so years, nursing schools have become university-based. "Nursing school was now independent of doctors," Brown explained. "Yes, we are taught to be patient advocates, but we are also taught to be a check on the doctor. The problem with that is we're only taught to see docs as adversaries," she told me. An essay by a nurse in the British Medical Journal echoes this idea. "Nurses have been indoctrinated with the belief that doctors are capable of exercising only a cold, scientific medical model," she writes. "They treat the disease, not the patient. Nursing literature is full of anecdotal accounts of the distant approach that doctors have towards patients and their careers."

As a result, Brown admitted that nurses "never get a good understanding of the stresses and strains of what it's like to be a physician." I told her that medical school provides next to nothing in terms of how nurses approach patients either.

"If that's the case, how do doctors and nurses learn to behave and negotiate with each other?" she asked. I didn't have an answer, but in reflecting on what she said, I realized that over the years, I hadn't made much of an effort to understand nurses myself. As a resident, for example, I never read a single note in a patient chart penned by an R.N. -- a "care plan" as they're usually called. They seemed extraneous to me, and doctors have argued that they don't impact their care of patients. But had I read them, I may have been able to bridge at least a small divide between me and the nurses who cared, side by side with me, for my pediatric patients.

We compared other notes. What do nurses want from doctors? I asked. "Respect, a willingness to listen even when we're bringing up something stupid, a sense that we're on the same team," Brown replied. Doctors demonstrate a great deal of variability in all of those things. Again, though, we agreed that this variability goes both ways. I've worked with, and continue to work with, amazing, caring and competent nurses. These are the R.N.s who would be my first-round draft picks, even over other doctors. On the other hand, I've been driven nuts by nurses who consistently botch a patient's care plan, misinform parents about their child's health, or simply refuse to do what's needed of them.

That brought up the next question: Can doctors and nurses hold one another accountable without picking the scabs off old emotional wounds? Her suggestion was that if there's conflict or a mistake made, debrief together. "Be honest, say what happened, work together to solve a problem." One way doctors do this is by having regular "morbidity and mortality meetings," where individual cases are discussed and the physicians involved are asked to explain why a patient was hurt or another bad outcome occurred. Nurses are not part of that process, and the tendency among them is to "just say something bad happened, not talk about it again."

"If we really want parity and respect we also need to be held accountable," she said. In principle, Brown has a point. In practice, the jury is out on how doctors and nurses can hold each other accountable when their skill sets are complementary but still very different.

Brown and I both agreed that bad behavior between health professionals (be it between doctors and nurses or even between doctors and other doctors) is bad for business. In her case, it's unforgivable that the doctor who chastised her didn't have the decency to confront her privately about any concerns. His goal wasn't to figure out what happened but, like a hot teakettle, merely to blow off steam. A recent survey suggests that this abusive behavior really is disturbingly common among physicians. That kind of behavior undermines the patient's confidence in his or her medical team, and we absolutely need teams to be successful in an era of medicine as complex as ours.

If there's one hope for both of us, it's our patients. As one observer points out, "for decades we understood the professions as a conventional nuclear family, with doctor-father, nurse-mother, and patient-child. But our hope for total wisdom and protection from father is forlorn, our wish for total comfort and protection from mother unachievable, and the patient has grown up. A new three-way partnership should displace this vanishing family."

Finally, I asked Brown which fictional character she might give credit to for being a more realistic portrayal of a nurse. "Nurse Jackie," she said.

A foul-mouthed, grouchy drug addict as an iconic nurse for the masses? Yes, she confirmed. Because Jackie is flawed, fallible and therefore as human as a nurse can be. I suspect that if all of us, doctors and nurses, embraced our own flaws, admitted our own fallibility and realized that we need each other every single day, we would take yet another step forward at getting better together.

Shares