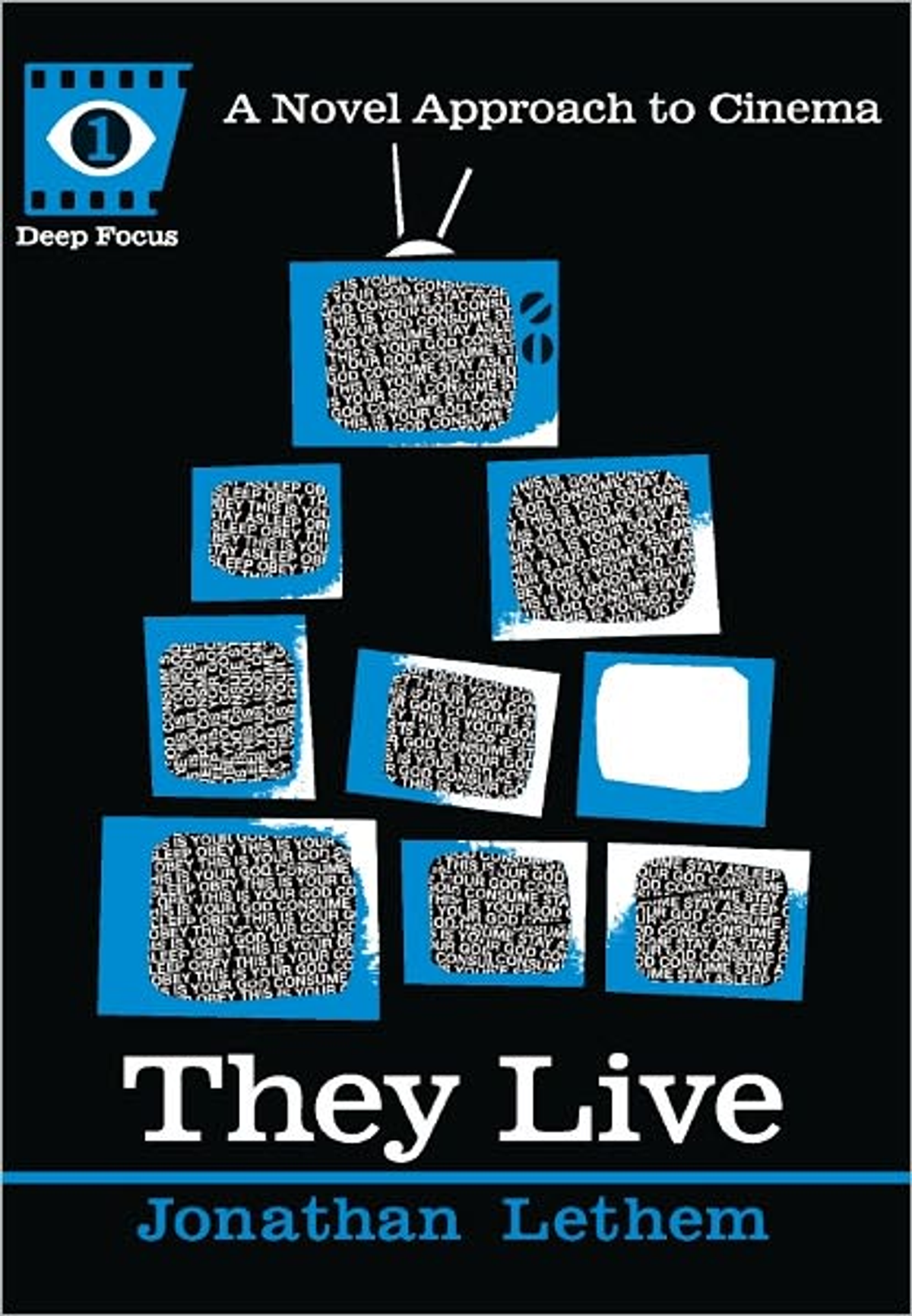

If the author had not been Jonathan Lethem -- award-winning novelist, brilliant essayist, recipient of a "genius grant" from the MacArthur Foundation -- I might not have opened "They Live," a slim critical monograph published last year concerning a late-1980s science-fiction-horror film I had never seen. When I did open it, I found epigraphs from Roland Barthes, Edgar Allan Poe, and "Mystery Science Theater 3000," and short, suggestive chapters with titles like "Note on Diegesis and Ideology and Peek-A-Boo" (on the film-theory terms Lethem finds indispensable) and "The Black Guy and the White Guy, Together Again for the First Time" (on a certain casting cliché in late-20th-century Hollywood action movies). I found shrewd and funny insights concerning the movie's key device, "a pair of sunglasses that reveal yuppies as alien ghouls." And I found a way of thinking about movies that was thorough, thoughtful, populist, and personal, all at once.

Happily, Lethem's book was the first in a series, called "Deep Focus" and edited by Sean Howe, who also edited "Give Our Regards to the Atom Smashers! Writers on Comics." Joining Lethem's book last fall was another surprising piece of pop scholarship: Christopher Sorrentino's take on "Death Wish," the Charles Bronson vehicle from 1974. A novelist like Lethem, Sorrentino is even less impressed with his object of study (a lot less impressed), but finds in both the movie and its reception (which consisted mostly of righteous opprobrium) much to mull about violence and its representation, New York in American cinema, high art and low, and so on. Throughout, Sorrentino makes an eloquent case for attentive viewing with an open mind: "We fail when we walk into a movie knowing in advance what we're going to see."

Happily, Lethem's book was the first in a series, called "Deep Focus" and edited by Sean Howe, who also edited "Give Our Regards to the Atom Smashers! Writers on Comics." Joining Lethem's book last fall was another surprising piece of pop scholarship: Christopher Sorrentino's take on "Death Wish," the Charles Bronson vehicle from 1974. A novelist like Lethem, Sorrentino is even less impressed with his object of study (a lot less impressed), but finds in both the movie and its reception (which consisted mostly of righteous opprobrium) much to mull about violence and its representation, New York in American cinema, high art and low, and so on. Throughout, Sorrentino makes an eloquent case for attentive viewing with an open mind: "We fail when we walk into a movie knowing in advance what we're going to see."

Now four more "Deep Focus" titles are on the way: Josh Wilker's "The Bad News Bears in Breaking Training," Matthew Specktor's "The Sting," John Ross Bowie's "Heathers," and Chris Ryan's "Lethal Weapon." There's a bit of a pattern here: So far the series seems, well, focused on the reactions of white American men born in the '60s and '70s to movies they first saw between the ages of 9 and 25, give or take. Which is not to say the sensibilities or approaches are uniform: Wilker's consideration of the much-maligned sequel to the classic baseball film is nostalgic and lyrical (really: one chapter is a poem); Bowie's book is a pleasing mix of memoir, analysis, and journalism (he interviewed the film's director and screenwriter, plus a couple of his high school girlfriends, both actually named Heather); Specktor's study is more straightforwardly analytical. (I've not yet seen Chris Ryan's entry in the series.)

Of these three, Bowie's is probably the best: He bounces with seeming ease from personal history to the history of the name "Heather," from close reading ("Westerburg High School" is a nod to the Replacements; "Sherwood, Ohio" alludes to the author of "Winesburg, Ohio") to a discussion of Columbine. Wilker, meanwhile, sometimes veers too far into beatnik romanticism for my taste, but he also endearingly evokes early adolescence and the odd attachments we form at that age to mediocre movies -- a heartfelt devotion that seems to drive each one of these books. "A dream of baseball," he calls his mediocre movie of choice, "of junk food, of the most uncomplicated happiness there could ever be, on the road with no one but other boys just like me, a baseball game to play, a season still alive, the coolest kid who ever lived at the wheel."

Shares