At its most basic level, a pseudonym is a prank. Yet the motives that lead writers to assume an alias are infinitely complex, sometimes mysterious even to them. Names are loaded, full of pitfalls and possibilities, and can prove obstacles to writing. Virginia Woolf, who never adopted a nom de plume herself, once expressed the fundamental and maddening condition of authorship: "Never to be yourself and yet always—that is the problem." She was describing the predicament of the personal essayist, but identity can seem crippling to any writer. A change of name, much like a change of scenery, provides a chance to start again.

To a certain extent, all writing involves impersonation—the act of summoning an authorial "I" to create the speaker of a poem or the characters in a novel. For the audacious poet Walt Whitman, it was possible to explore other voices simply as himself. He embraced his multitudes. ("Do I contradict myself? / Very well then, I contradict myself.") But some writers are unable to engage in such alchemy, or don't want to, without relying on an alter ego. If the authorial persona is a construct, never wholly authentic (no matter how autobiographical the material), then the pseudonymous writer takes this notion to yet another level, inventing a construct of a construct. "The cultivation of a pseudonym might be interpreted as not so very different from the cultivation in vivo of the narrative voice that sustains any work of words, making it unique and inimitable," wrote Joyce Carol Oates in a 1987 New York Times essay. "Choosing a pseudonym by which to identify the completed product simply takes the mysterious process a step or two further, officially erasing the author's (social) identity and supplanting it with the (pseudonymous) identity." Elide your own name, and imaginative beckoning can truly begin. As the French journalist and writer François Nourissier once noted (in a piece titled "Faut-il écrire masqué?"), a nom de plume provides a space in which "obstacles fall away, and one's reserve dissipates."

The merging of an author and an alter ego is an unpredictable thing. It can become a marriage, like a faithful and sturdy partnership, or it can prove a swift, intoxicating affair. A clandestine literary self can be tried on temporarily, to produce a single work, then dropped like a robe; or the guise might exist as something to be guarded at all costs. The attraction is obvious and undeniable. Entering another body (figuratively, ecstatically) is almost an erotic impulse. Historically, many writers have been lonely outsiders, which is why inhabiting another self offers an intimacy that seems otherwise unobtainable. In the absence of real-life companionship, the pseudonymous entity can serve as confidant, keeper of secrets, and protective shield. The term "alter ego" is taken from Latin, meaning "other I." This suggests the writer is not so much wearing a mask as becoming another person entirely. Have the two selves met? Maybe not, and it's probably better that way. Sometimes there's no reason to explore how or why the other half lives. Knowing that it does is enough.

In his influential 1974 book "The Inner Game of Tennis," author Timothy Gallwey applied the notion of doubleness to the tennis player, describing how each self hinders or enhances performance. With almost no technical advice, he provides a prescriptive guide to mastery. He focuses on what he describes as two arenas of engagement: Self 1 and Self 2. When his book was first published, Gallwey's ideas were so radical that thousands of readers wrote to express their gratitude, saying that they'd successfully applied his principles to pursuits other than tennis, including writing.

Gallwey, who majored in English literature at Harvard University, portrays Self 1 as "the talker, critic, controlling voice," and notes its "persistence and inventiveness in finding opportunities to get in the way." Self 1 berates you, calls you an incorrigible failure. But the nonjudgmental Self 2 represents liberation in its purest form. As Gallwey writes, Self 2 is "much more than a doer. It is capable of a range of feelings that are the most uniquely human aspect of life. These feelings can be explored in sports, the arts ... and countless other activities. Self 2 is like an acorn that, when first discovered, seems quite small yet turns out to have the uncanny ability not only to become a magnificent tree but, if it has the right conditions, can generate an entire forest." In the context of authorship, the freeing of an alternate identity (Self 2) can reveal not just a forest but new worlds, boundless and transgressive, thrilling beyond one's wildest dreams.

A pseudonym may give a writer the necessary distance to speak honestly, but it can just as easily provide a license to lie. Anything is possible. It allows a writer to produce a work of "serious" literature, or one that is simply a guilty pleasure. It can inspire unprecedented bursts of creativity and prove an antidote to boredom. For that rare bird known as the commercially successful author, there is typically less at stake in toying with a pen name. If the book produced by an ephemeral self fails, it will be viewed as a silly misstep. All is forgiven when an author retires a pen name and returns to giving critics and fans exactly what they want: the familiar. Lesson learned, let's move on. If you're writing the equivalent of high-fructose corn syrup, perhaps it's unwise to serve up organic spelt, even under a different brand name.

For best-selling authors like Nora Roberts (a truncated version of her actual name, Eleanor Robertson)—who has written more than 200 novels, including those under the pen name J.D. Robb—having a transparent or "open" pseudonym is a savvy marketing strategy, a way to keep up her busy production line and show off her versatility. Roberts had initially resisted writing as someone else, but her agent had talked her into it by explaining, "There's Diet Pepsi, there's regular Pepsi, and there's Caffeine-Free Pepsi." It's all about brand extension.

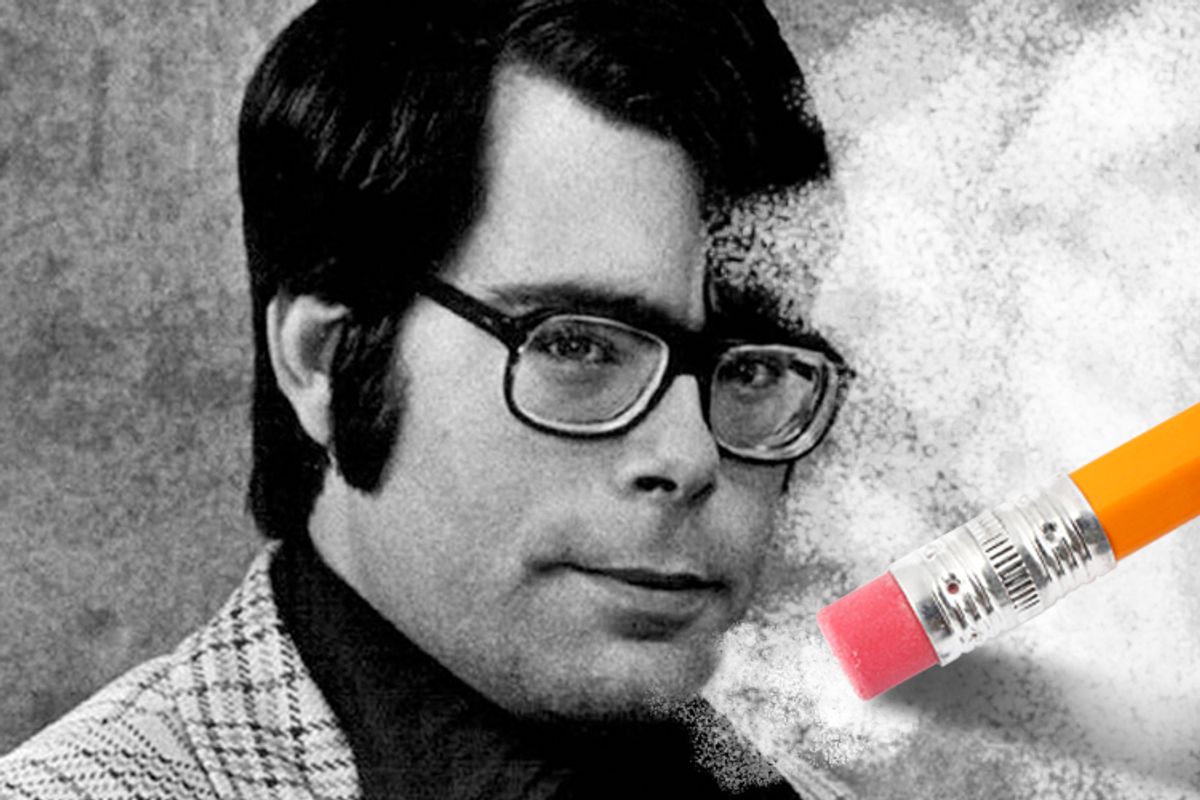

A new work by Stephen King, whose books have sold more than 500 million copies worldwide, is a reassuring promise of success to his publisher. It's also critic-proof. Yet in the late 1970s, feeling hemmed in by his phenomenally prolific output, King introduced the pen name Richard Bachman. As he later said, it was easy to add someone to his interior staff:

The name Richard Bachman actually came from when they called me and said we're ready to go to press with this novel, what name shall we put on it? And I hadn't really thought about that. Well, I had, but the original name—Gus Pillsbury—had gotten out on the grapevine and I really didn't like it that much anyway, so they said they needed it right away and there was a novel by Richard Stark on my desk, so I used the name Richard, and that's kind of funny because Richard Stark is in itself a pen name for Donald Westlake, and what was playing on the record player was "You Ain't Seen Nothin' Yet" by Bachman Turner Overdrive, so I put the two of them together and came up with Richard Bachman.

King's practical measure to avoid saturating the market (and avoid openly competing with himself for sales) was a success. But in 1985, a bookstore clerk in Washington, D.C., did some detective work and exposed King's secret. The author subsequently issued a press release announcing Bachman's death from "cancer of the pseudonym." King dedicated his 1989 novel "The Dark Half" (about a pen name that assumes a sinister life of its own) to "the late Richard Bachman."

Prominent writers such as Robert Ludlum, Joyce Carol Oates, Anthony Burgess, Anne Rice, Michael Crichton, John Banville, Ruth Rendell, and Julian Barnes are also known to have indulged in pseudonymous publication. The Nobel laureate Doris Lessing, who tested out a nom de plume in the early 1980s, learned that she was better off sticking with her own identity. One of her aims had been a respite from the public's perception of her work; she sought to upend preconceptions of what it meant to read a "Doris Lessing novel."

In the 19th century, the curious phenomenon of pseudonymity reached its height, and as early as the mid-16th century, it was customary for a work to be published without any author's name. It is interesting that the decline of pseudonyms in the 20th century coincided with the rise of television and film. As people gained more access to the lives of others, it became harder to maintain privacy—and perhaps less desirable. In today's culture, no information seems too personal to be shared (or appropriated). Reality television has increased our hunger to "know" celebrities, and even authors are not immune to the pressures of self-promotion and self-revelation; we are in an era in which, as the biographer Nigel Hamilton has written, "individual human identity has become the focus of so much discussion."

This is not entirely new, but with the explosion of digital technology, things seem to have spiraled out of control. Fans clamor to interact, online and in person, with their favorite writers, who in turn are expected to blog, sign autographs, and happily pose for photographs at publicity events. Along with their books, authors themselves are sold as products. Even though the practice of pseudonymity is still going strong, it has lost the allure it once had, and for the most part it is applied perfunctorily in genres such as crime fiction or erotica. Today, using a pen name is less often a creative or playful endeavor than a commercial one. Reticence is not what it used to be.

Carmela Ciuraru is not a pseudonym. Her anthologies include "First Loves: Poets Introduce the Essential Poems That Captivated and Inspired Them" (Scribner) and "Solitude Poems" (Alfred A. Knopf/Everyman’s Library). She is a member of the National Book Critics Circle, and has written for a number of publications, including the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, the Wall Street Journal, the Boston Globe, the Washington Post and Newsday. This article is an adapted excerpt from her new book, "Nom de Plume: A (Secret) History of Pseudonyms."

Shares