"Page One: Inside the New York Times," Andrew Rossi's oddly exciting documentary about the august and struggling flagship of American journalism, is a movie without an ending. How could it be otherwise? We don't know how it's going to end for the Times, for "old media," for the so-called profession of journalism (a recent and amorphous invention) or, for that matter, for our perishing republic. All signs point to No, as the Magic 8-Ball might put it. But whether you view "Page One" as an inspirational call to arms or a chronicle of the Last Flight of the Noble Pteranodon -- hey, why is the sky getting darker? -- it's full of juicy, chewy nuggets for journalists, journalist-haters and news junkies.

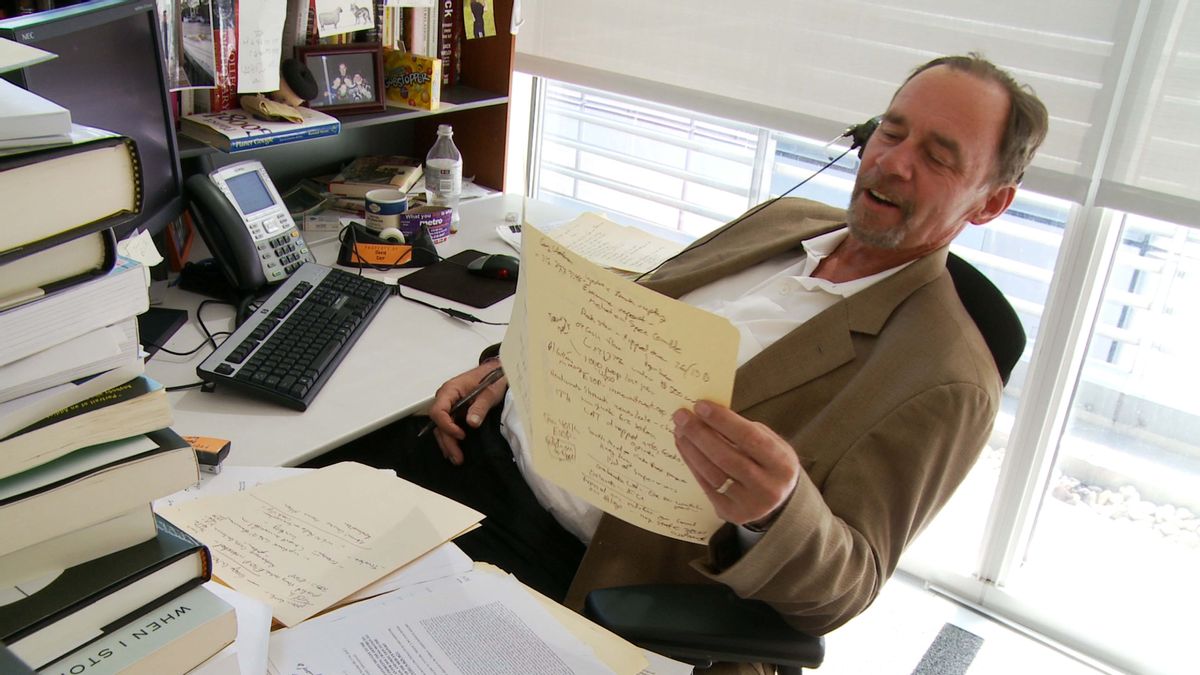

Initially, Rossi's decision to document life at the Times' relatively new media desk threatens to become one of those self-regarding, head-up-butt endless loops so common in contemporary culture: A movie about reporters who write about media. Please re-re-re-tweet. But hard-boiled, asphalt-voiced media reporter David Carr (a longtime professional acquaintance of mine) does indeed make for a natural focus, both because he's a colorful character and because he epitomizes the craft and integrity the Times is supposed to represent, and has intermittently upheld. Carr appeared before the New York premiere I attended to evangelize a little on the paper's behalf. "We provide efficacious information in a timely manner that the world can rely on," he growled at a theater packed with Times staffers. "There ought to be a business in that."

Well, yes. Now, given the Times' long record as a stenographic courtier to the United States' foreign policy, military and intelligence bureaucracies, and its venerable tradition of lameness on cultural topics, one might be justified in adding that it depends what you mean by "efficacious" and "timely." And for that matter by "rely" and "the world." But let's stipulate that in the fullness of Times history Carr's summary may be more accurate than not. At any rate, "Page One" demonstrates that 2009 and 2010 were exciting times at the media desk, which had to cover a spreading sinkhole of a story -- the nationwide collapse of daily newspapers -- that posed an existential threat to the Times itself.

Carr also cracked wise at the premiere audience about the inherent difficulties involved in filming a largely solitary and sedentary occupation. "I looked around the place at all these people sitting in their cubes typing, with headphones on, and said, 'What about this doesn't say movie?'" But Rossi does an admirable job of making it all seem dramatic and dynamic, taking us inside the Times' legendary Page One meetings (attended only by top-level desk editors), and exploring the divergent work styles of Carr, an old-school shoe-leather reporter, and one-time collegiate blogger Brian Stelter, his fully wired, Twitterific, multitasking younger colleague.

Along the way, Rossi captures Carr and his editor, Bruce Headlam, as they wrangle perhaps the media desk's biggest-ever enterprise, a 5,000-word exposé of the profligate mismanagement and abusive frat-boy culture that led the Tribune Company -- owner of the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune and several other once-major papers -- into bankruptcy. It was an outstanding work of old-school investigative journalism that took several weeks to report, write, edit, double-check and prepare for publication, and it's doubtful that any other newspaper (or any Internet publication) could have done it even half as well.

That last fact is simultaneously shocking and thoroughly unsurprising, and points us toward overlapping aspects of journalism's current dilemma. On one hand, the near-total isolation of the Times, which now faces no American competitors anywhere near its size or scale or level of globe-covering ambition, can lead to a sense of arrogance and entitlement (as if the paper's borderline-intolerable air of Ivy League privilege weren't enough). Carr himself uses the phrase "New York Times exceptionalism," meaning a sort of religious faith that the paper is too important to the future of democracy, or whatever, to fail. On the other, techno-utopians who crow over the Times' missteps and misfortunes, and naively assume that some undefinable citizen-journalism something will fill the gap if it collapses, may be inviting a civic Armageddon, in which politicians, lobbyists and corporations do whatever the hell they want while the rest of us read TMZ and Gawker. (I'm not slamming those publications, which did not invent the concept of giving the public what it wants. But even the people who make Snickers don't believe that asparagus farms should be burned down.)

If the Times looks muscular and manly covering the Trib story, it doesn't come off nearly as well in reacting to the WikiLeaks revelations of 2010 and the ensuing media firestorm around Julian Assange. Those events lead to a lot of backstage hand-wringing inside the paper about whether or not Assange is a legitimate journalist and how to frame his problematic relationship with the Times. Foreign desk editor Susan Chira, apparently unaware that she's embarrassing herself, admits that she had never heard of WikiLeaks before the group's first leaks of Afghan war video (even though the Times had reported on it several times), and then insists that WikiLeaks is only a source, and not a Times partner (in direct contradiction of her boss, executive editor Bill Keller).

This may be oversimplifying a rapidly shifting situation, but after seeing "Page One" you're forced to conclude that the Times remains most comfortable, as an institution, with situations where conventional distinctions between reporter, sources, subject matter and audience still hold, as in Carr's Tribune story. WikiLeaks threw all those relationships into crisis, perhaps on purpose. As Keller explains to Rossi's camera, there's a big difference between the WikiLeaks releases and the Pentagon Papers case of 1971. Daniel Ellsberg needed a partner like the Times to get his information to the public, and Assange didn't. Arguably, releasing material through the Times (along with the Guardian and Der Spiegel) lent WikiLeaks' activist quest greater legitimacy and currency, but the newspapers needed Assange more than he needed them.

In fairness, I really can't tell how many civilians will be interested in "Page One," or what they'll see in it, but Magnolia Pictures plans an ambitious nationwide release. I generally find the phenomenon of journalists debating the future of journalism pretty tedious, but I've also been a New York journalist for 16 years, and have met Carr and several other people who appear in the movie. Certainly the Times has long been the object of a national fascination, composed of nearly equal parts veneration and loathing, and for decades has been viewed in certain quarters as a bastion of left-wing anti-Americanism (and in others as a boot-licking lackey of the State Department).

It's easy to luxuriate in the schadenfreude of the Times' worst scandals, from Jayson Blair and Judith Miller to the El Mozote massacre and Walter Duranty's coverage of Stalin -- I'll wait while you look those last two up -- and I've certainly done it. But I still go out every morning and get that blue, plastic-wrapped package off my doorstep with great anticipation (yes, I get the damn thing delivered, as I have for almost 20 years). For better and for worse the Times is a uniquely important institution in American society, and not having it to study and pick apart and argue against would be the worst scandal of all. That said, I strongly suspect it's going to have to change radically and rapidly, far more so than anyone who works there wants it to, if it's going to survive.

Rossi's film makes a compelling case on behalf of the traditional values of journalism -- a disinterested search for "the best available version of the truth," as veteran Washington Post reporter Carl Bernstein puts it -- and the necessity of adapting those to a new media age where almost everything about the way information is delivered and consumed has changed. Obviously Salon, along with quite a few other Internet publications, is involved in the same struggle, and I'm not going to claim that any of us has it figured out. As the final images of this would-be inspirational opus about craft, collaboration and integrity in an era of melting standards fade from the screen, you can't help suspecting that the Gray Lady's great struggle is only beginning.

"Page One: Inside the New York Times" opens June 17 at the Angelika Film Center and Film Society of Lincoln Center in New York; June 24 in Los Angeles, Hartford, Conn., and New Haven, Conn.; and July 1 in Ann Arbor, Mich., Atlanta, Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, Indianapolis, Las Vegas, Minneapolis, Omaha, Philadelphia, Phoenix, Portland, Ore., St. Louis, San Diego, San Francisco, San Jose, Calif., Washington, Seattle and Austin, Texas, with many more cities to follow.

Shares