I made a manful effort to resist Cindy Meehl's documentary "Buck," and its plain-spoken protagonist, a legendary horse trainer with the you-couldn't-make-this-up name Buck Brannaman. Ultimately it was impossible. Now, many of the objections that people might raise in the abstract to a movie like "Buck" are ones I agree with: It's an exercise in rural, nostalgic Americana, which seems far away from the urban-suburban polyglot nation most of us live in. It's a moral-biographical fable calibrated to appeal to a "This American Life"-style adult audience, who don't often go to the movies and only see documentaries if Michael Moore, Michael Pollan or Al Gore is involved.

Now, if you think those are bad things in themselves, then "Buck" may well provoke a severe allergic reaction and you should stay away. But if you're less invested in impressing yourself with your own coolness than that, you'll find a haunting, beautifully told tale about a genuine American original, who survived a childhood of violent abuse to become a leading figure in new-school horse training. Colts used to be trained, or "broken," much the way young Buckshot Brannaman was trained as a rope-trick artist by his rural Montana father, through beatings and humiliation and all-around subjugation. Of course that still happens sometimes, but Brannaman and other leading figures in "natural horsemanship" have spent the last several decades evangelizing a different path, based on understanding equine psychology and fostering communication and cooperation between horse and rider. (They speak of "starting" colts, for instance -- beginning their lives of working with people -- rather than breaking them.)

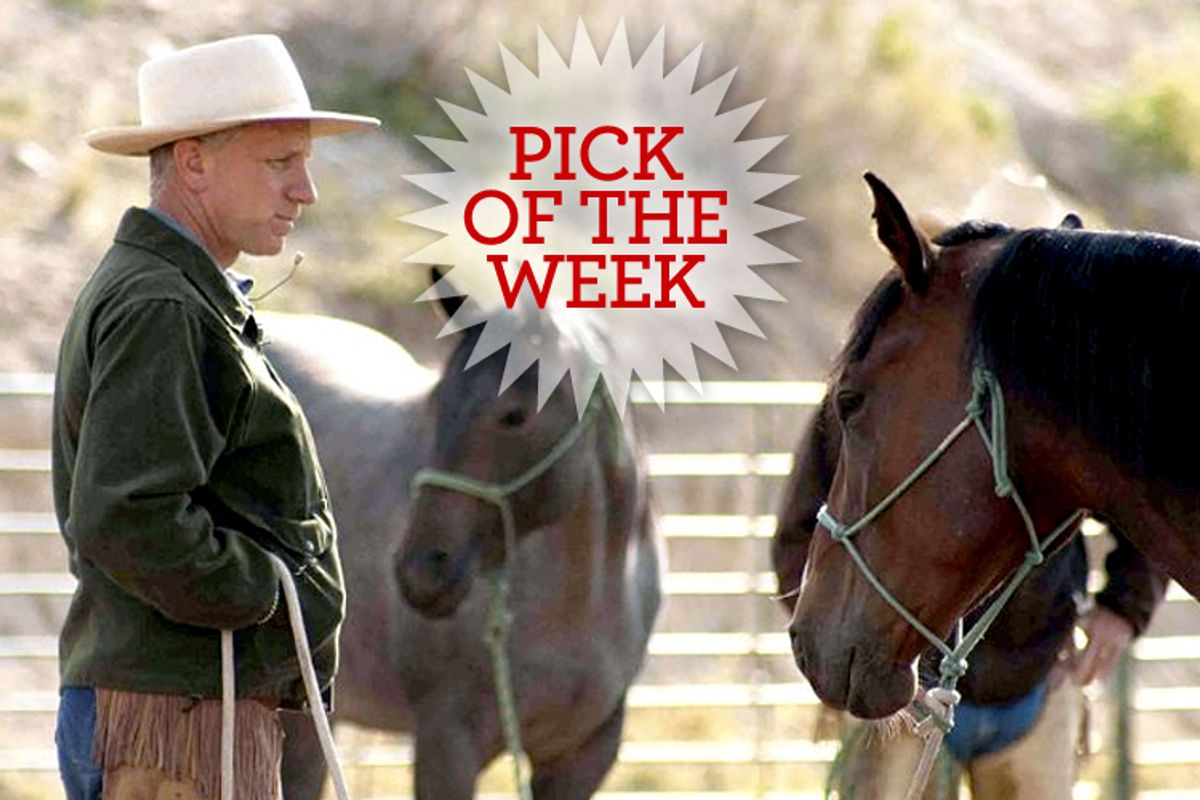

I assume there are animal-rights activists who view Brannaman's approach as the friendly face of fascism, although that doesn't come up in "Buck." Still, it's hard to resist the evidence we see in the film, when time after time Brannaman takes on some fractious, troubled horse and within a few minutes gets it to do what he wants, without any physical force. His demeanor is somewhere between Tiger Mom and Zen teacher, calm, confident and a little detached. He lets the horse know clearly that bad behavior is unacceptable, but never gets angry or emotional. And when the horse cooperates, it's no big deal. He gives it a pat or two and says a few gentle words, but the animal's tangible relief at a non-stressful interaction with a non-freaked-out human being is clearly its own reward.

Brannaman was indeed the principal model for Nicholas Evans' novel "The Horse Whisperer," and served as a crucial on-set consultant on Robert Redford's film version. (Redford appears here in an interview, and we see set photographs of Brannaman with the film's teenage co-star, Scarlett Johansson.) But as Meehl follows Brannaman across the picturesque reaches of American horse country -- he travels almost everywhere there's open space and horse farms, from Maine to North Carolina and clear across the country to the northern Plains and the Pacific Northwest -- "Buck" gradually reveals that his real therapeutic clients are not horses but the people who've screwed them up. As he puts it, the animals who live with us serve as mirrors, and we may not always like what we see.

The film's startling climax comes at an otherwise innocuous Brannaman seminar in Chico, Calif., where he's confronted with a nearly feral orphan colt who has attacked and severely injured his owner. Eventually Brannaman turns on this young woman in a spirit of Dr. Phil intervention, telling her that the ways she has alternately spoiled and abused this young stallion say a lot more about her than about the horse. It's the only time in the whole movie we see him angry (or see him unable to communicate with a horse), and the woman is reduced to tears. But he's right, of course, and in that moment all the themes Meehl handles so delicately come together: The connection between Brannaman's horrific childhood and his career, the reasons why he spends almost all his time on the road and rarely sees his wife and daughter, the fact that we can get past trauma and keep on working -- we all have to do that, albeit on a less dramatic scale -- but we never really forget it and can't undo it.

"Buck" is now playing in New York and Los Angeles. It opens June 24 in Atlanta, Baltimore, Boston, Charlotte, N.C., Chicago, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, Indianapolis, Miami, Palm Beach, Fla., Philadelphia, Portland, Ore., St. Louis, San Diego, San Francisco, Santa Barbara, Calif., Sarasota, Fla., Washington, Seattle and Austin, Texas, with many more cities to follow.

Shares