A roving look into the diaries, journals, and field notebooks of several of this generation's most celebrated natural scientists, Michael Canfield's "Field Notes on Science and Nature" raises the curtain on where "science happens," allowing readers behind-the-scenes glimpses of the rough-draft places from which serious inquiry springs. Focusing on notes taken in the field -- as well as the doodle, the observation-in-passing, the daydream -- Canfield invites his readers to peer over the shoulders of natural historians in their first raw moments of observation.

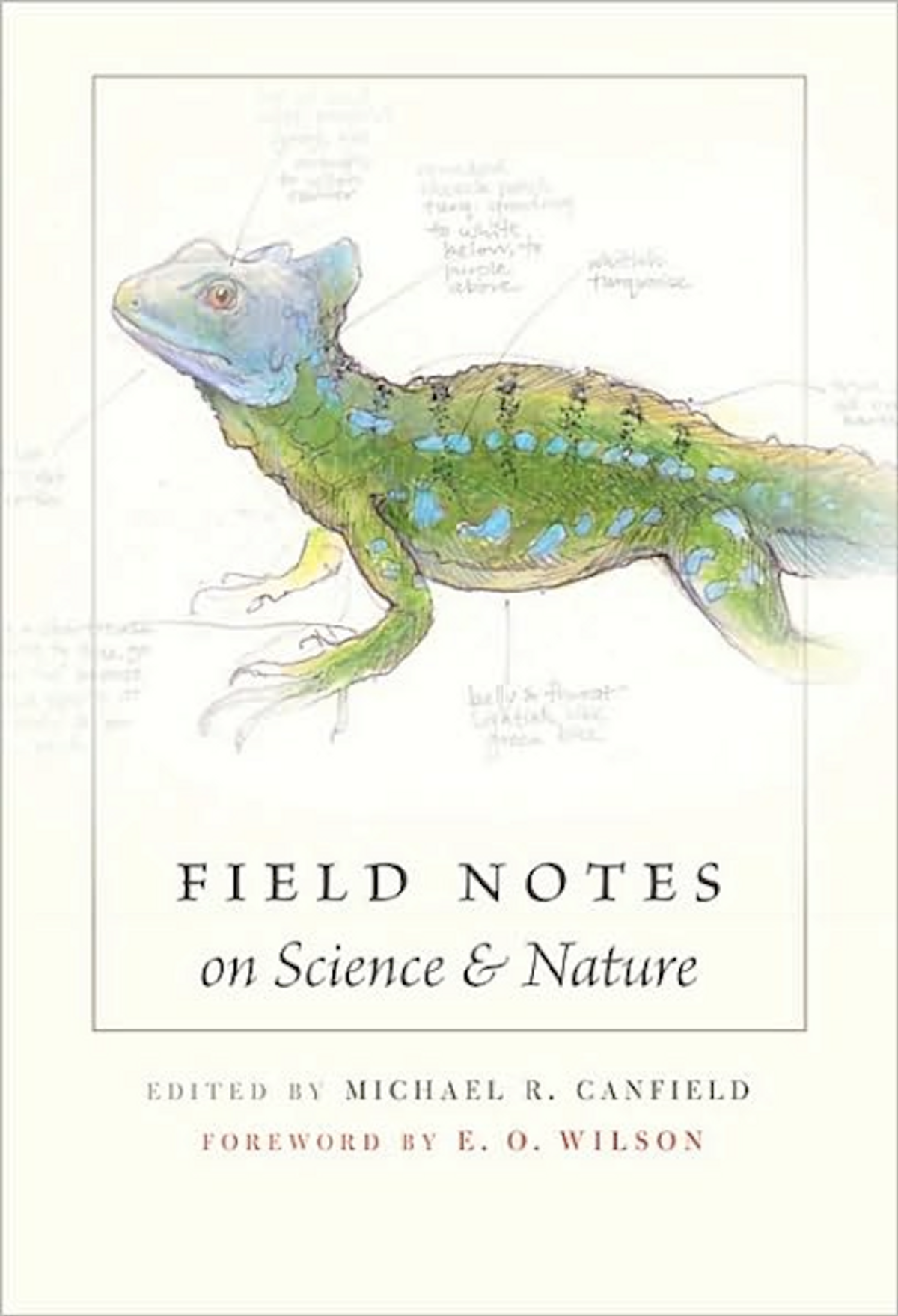

As such, this book of meditative essays is interspersed with lush facsimiles of just such notebooks, often accompanied by sketches of butterflies, charts of soil strata, or memories of weather and light. In the era of the laptop and iPhone, readers can see what the Moleskine can still accomplish as a place for thought to assemble, and observe how the act of careful recording can give rise to great and meaningful discovery. Ranging from etymologists to paleontologists to avian specialists, the essayists gathered in this collection share a common love of watching and writing, and a keen ability to articulate how both of these things form the first tier of human investigation. Whether we're learning the way a passing thought about how a crane flies became a discovery of the way a species protects itself, or hearing about an expert who developed his own finely honed philosophy of list-making, or reading how journal entries about raven behavior led to a book, we're gifted with an understanding of how note-taking becomes the first place to frame a world.

As such, this book of meditative essays is interspersed with lush facsimiles of just such notebooks, often accompanied by sketches of butterflies, charts of soil strata, or memories of weather and light. In the era of the laptop and iPhone, readers can see what the Moleskine can still accomplish as a place for thought to assemble, and observe how the act of careful recording can give rise to great and meaningful discovery. Ranging from etymologists to paleontologists to avian specialists, the essayists gathered in this collection share a common love of watching and writing, and a keen ability to articulate how both of these things form the first tier of human investigation. Whether we're learning the way a passing thought about how a crane flies became a discovery of the way a species protects itself, or hearing about an expert who developed his own finely honed philosophy of list-making, or reading how journal entries about raven behavior led to a book, we're gifted with an understanding of how note-taking becomes the first place to frame a world.

It's highly nerdy stuff, but it's human and humane as well. University of Vermont Emeritus Professor Bernd Heinrich describes his note-taking addiction this way: "I use any stray implement at hand. I have no system, no object or goal in mind. The notebook allows for spontaneity, a counterbalance to my ideal of orderly scientific objectivity. The process slows my thinking and serves as a first crude filter for the natural breeze of data that passes by in a continual stream." Heinrich's writing doesn't record thinking; it makes thinking possible. What's more, in each of these essays, scientists' notebooks embody the place where the seemingly objective process of science begins in hunch, intuition, or seemingly whimsical speculation, the place where the possible asserts itself.

Although the book seems geared to Canfield's fellow scientists, scientists aren't the only ones who might profit from it. Looking at these well-kept journals is like looking into an artist's sketchpad, a journalist's reporting notes, or a composer's first drafts. We see the activity of a mind sorting out the world and framing it, asking, "what is the question that will illuminate some part of the truth?" Or "what is the constellation of thought with which I will play?" Out of these drafts some essence reveals itself, and to each of these scientists this process still has the luster of mystery. At its base this book is about science, but it's also about the liveliness of the human mind practicing any craft, and about the kinetic, surprising places from which any human knowledge springs.

Shares