Seven years ago early in the morning of June 1, my father's nurse woke me to say, "Your father has passed." I sat vigil alone at the foot of his bed, glancing at his face and then away, because it was hard to look at him. His mouth hung open, perhaps from trying for a last breath that never came.

I finally got a glimpse of who he was as a person, though that person had departed an hour ago. Despite walls plastered with awards, numerous bestsellers, bushels of adoring fan mail and the company of great men, his face was etched with disappointment.

As a boy, my vision of my father was hindered by physical fear. All I saw was a giant, one who would periodically strike me to unleash his rage.

Just as I became a man, my father, William Manchester, rocketed to international fame after the publication of his bestseller "The Death of a President." Now he towered over me in the world. All I saw was how much he had achieved and how little I had in comparison.

Just as my father reached the age I am now, 60, the mask of the famous author slipped and I saw a very different face, that of his shadow.

As the skeletons clattered from our family closet -- my father's secret lifetime of self-destructive habits, his marriage that was something out of a horror movie -- I could only blink in disbelief. How could these two men, these two lives, coexist in a single body?

Was he a writer of tireless discipline, who could work around the clock, who published 18 books, some over a thousand pages long? Or the man powerless in the face of his addictions?

Was he the man who'd met four presidents, who'd fought Bobby and Jackie Kennedy and won? Or the husband who sat alone in his own home because his wife wouldn't let his friends inside, not even his brother?

Was he the Marine who received a Navy Cross for grabbing a machine gun and running up a hill into an enemy position? Or was he the person who cowered before his dentist, who was afraid to fire secretaries, who could barely stand to enter a roomful of strangers?

Eight years before my father died, his heart was within days of giving out on him. I drove him to the hospital for a quadruple bypass, acutely aware that these might be our last moments together. I asked him how he felt -- to offer comfort, to touch his heart just once while I still could. He said, "I'm not afraid. I stared death in the face on Okinawa and said, 'Fuck you!'" We rode the rest of the way in silence.

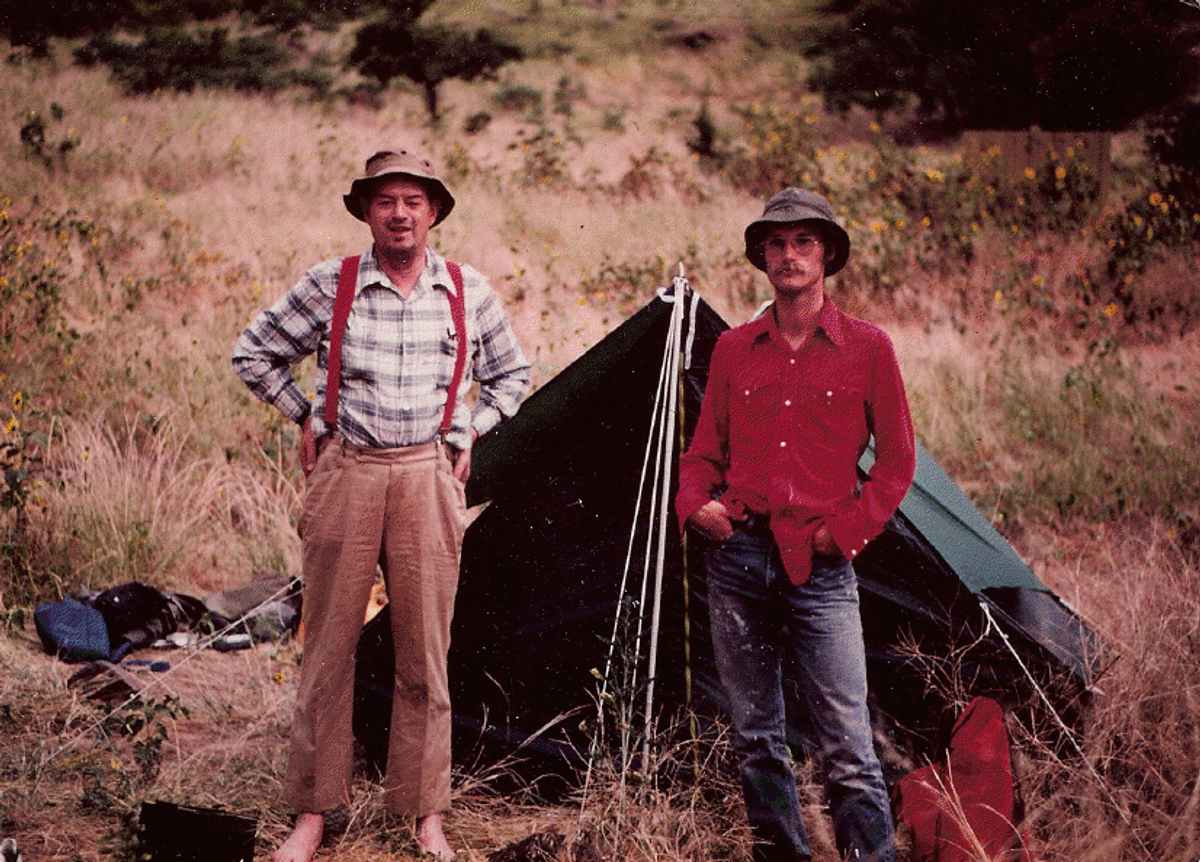

It's the tough Marine whose picture stares, pipe clenched in his teeth, from the cover of his 1980 memoir of combat, "Goodbye Darkness." After he died I found a series of outtakes from that photo shoot. He mugs for the camera, putting on mask after mask. What stuck with me was the one of him grinning, saturnine, all powerful. But not one of them was really him.

When the mother of my childhood best friend died, a woman who was dear to my entire family, my father delivered the eulogy. He was overcome by tears and could barely finish speaking. I had never seen my father cry. Maybe this was the real person coming out at last. But in the car after the funeral he said, "I disgraced myself."

He was a frail boy, terrible at sports. His father beat him, demanding, "Don't cry." The jeers of his peers and blows of his father rained down on a person of extraordinary sensitivity. That sensitivity would later prove a valuable asset for him as a writer. But as a youth he could only cover it in thick armor. That armor served him well in literal combat. It also closed him off from feelings of fear and loneliness.

What he felt instead were the extraordinary highs and lows of his fluctuating self-esteem. He'd always suffered mood swings, but fame and chemicals escalated their intensity. He was forever on top of the world or at the bottom of the deepest pit, never in between.

I spoke with one of his few surviving Marine buddies, who offered this simple wisdom, "Your father was just a man. A good man, but just a man."

And there's the real person that neither of us could ever see: just a man.

Shares