Since at least the Iraq War if not earlier, chickenhawkery has been a hallmark of American politics. From the 101st Fighting Keyboarders to the professional Draft-Dodging Neoconservatives to the Self-Labeled "Liberal Hawks" who disproportionately populate Washington green rooms, our nation's scowling legion of chickenhawks has sculpted a new archetype -- that of the chest-thumping pundit/politician who aggressively demands others fight and die in wars, but who himself either refuses to enlist or fled the battlefield when his country called.

What makes chickenhawkery such a distinctly American phenomenon is our culture's coupling of aggressive militarism with a lack of anything even resembling shared sacrifice. Quite bizarrely, we celebrate those who rhetorically promote wars as "tough" and "strong" without requiring those very warmongers to walk their talk. Shielded from any personal risk of injury or death, the chickenhawk is thus permitted to wrap himself in an American flag and goose step his way through television studios as the alleged personification of patriotic bravery.

For years, chickenhawkery's roots in this culture of unshared sacrifice have been a matter of theory -- albeit a logical, well-grounded theory. But now, thanks to a comprehensive new study, we have concrete data underscoring the hypothesis. It suggests that many Americans' aggressively pro-war ideology may fundamentally rely on their being physically shielded/disconnected from the human cost of war.

To document this connection, Columbia's Robert Erikson and University of California at Berkeley's Laura Stoker went back to the Vietnam War -- the last time Americans faced wartime conscription. The researchers analyzed data from the Jennings-Niemi Political Socialization Study of college-bound high schoolers and subsequent interviews of those same high-schoolers from 1965 onward. In the process, they discovered that men holding low draft lottery numbers (and therefore more at risk of being drafted into combat) "became more anti-war, more liberal, and more Democratic in their voting compared to those whose high numbers protected them from the draft." Importantly, for these men "lottery number was a stronger influence on their political outlook than their late-childhood party identification." That influence transcended previous party affiliation and made a permanent impact on their politics into adulthood.

"Men with vulnerable numbers show evidence of totally rethinking their partisanship in response to the threat of the draft," the researchers report. "Republicans in the group abandoned their party with unusual frequency, while even Democrats moved toward the independent category with slightly greater frequency than others."

By contrast, "for men with safe lottery numbers, the continuity of party identification" -- and militarist ideology -- "was relatively unaffected by the draft."

Reporting on the study, Miller-McCune notes:

Why did the prospect of being drafted make such a strong and lasting impact on the men's ideological outlook? Erikson and Stoker suggest this may be a case of self-interest trumping abstract ideas. They note that the risk of being drafted provoked intense "anxiety and fear," which caused many to rethink previously held beliefs, either as a direct emotional response or because it prompted them to get better informed.

This part of the study about "self-interest" is almost certainly the key factor in two generations' worth of high-profile chickenhawkery.

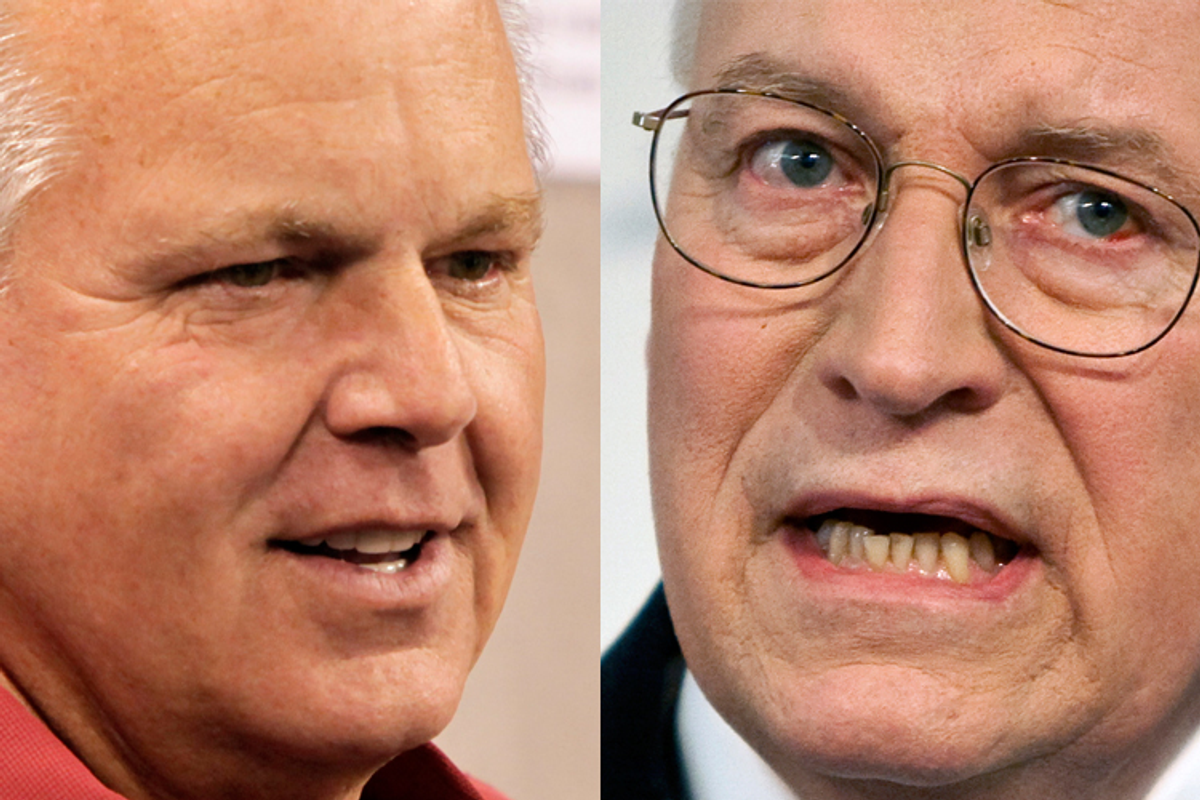

For chickenhawks like Rush Limbaugh and Dick Cheney who grew up during Vietnam conscription, deft draft-dodging provided them safety and psychological distance from bloodshed. As the data show, compared to draftees, that distance likely made them feel comfortable demanding other people face death on the battlefield, knowing that they wouldn't face such a fate themselves. Put another way, having avoided the draft, there was no "self-interest" in opposing war -- indeed, there was only self-interest in promoting wars in a media and political environment that increasingly rewarded rank bellicosity.

For younger, post-Vietnam-era chickenhawks (think, say, the chipper lily-white warmongers who populate the editorial staff of tiny-circulation elite Washington magazines like the National Review, New Republic and Weekly Standard) the same dynamic remained. Despite living in an era of "persistent conflict," these precocious youngsters never faced a lottery or draft (or even the threat of a modest tax hike!). So, just like their older brethren, their incessant demand that other people go off to die in wars never comes with even the vague possibility that the chickenhawks themselves will have to leave their comfortable D.C. offices and face the bloodshed they so vehemently endorse. And as the data show, without such a possibility, people seem far more supportive of militarism. That's especially true for chickenhawks in today's war-glorifying media, where "self-interest" is now defined as warmongering, not the opposite.

No doubt, the antiwar voices who have recently argued for the reinstatement of a draft will find fuel in this Berkeley/Columbia report. They argue that viscerally connecting the entire nation to the blood-and-guts consequences of war will make the nation less reflexively supportive of war -- and the new data substantively supports that assertion. That's why in the midst of (at least) three U.S. military occupations, this report is almost sure to be ignored by our chickenhawk-dominated political class -- because it too explicitly exposes the selfish, self-centered and abhorrent roots of the chickenhawk ethos that now plays such an integral role in perpetuating a state of Endless War.

Shares