All dog owners tend to think their dogs are amazing, just as all parents think their children are above average. But after you've read "Amazing Dogs: A Cabinet of Canine Curiosities," by Jan Bondeson, Rover's skill at fetching might look a little less impressive. Can your dog carry on a conversation in German, like Don the Talking Dog? Can he multiply large numbers, pick chosen cards out of a deck, or tell time from a watch like Munito, who was known to his Parisian fans in the 1810s as "le Newton de la race canine"?

And let's not forget the females -- like Lola, a second-generation dog prodigy, who came home to her owner one day "in a state of great depression," and tapped out a confession on the alphabet cards she used to communicate: "My honor is gone!" "Fraulein Kindermann understood that she must have enjoyed a short affair with a farmyard dog," Bondeson writes, "who had basely seduced and then left her. She tried to console poor Lola, saying that her broken heart would recover with time, but the pathetic dog responded 'Only when I die!'"

And let's not forget the females -- like Lola, a second-generation dog prodigy, who came home to her owner one day "in a state of great depression," and tapped out a confession on the alphabet cards she used to communicate: "My honor is gone!" "Fraulein Kindermann understood that she must have enjoyed a short affair with a farmyard dog," Bondeson writes, "who had basely seduced and then left her. She tried to console poor Lola, saying that her broken heart would recover with time, but the pathetic dog responded 'Only when I die!'"

As this passage shows, Bondeson, a Welsh rheumatologist, often writes with tongue in cheek. The most amazing thing in "Amazing Dogs," he knows, is the readiness of human beings to believe their dogs capable of such feats. This is not a new phenomenon -- the ancient world had its share of prodigious pets, as well, though they tended to be amazing for their loyalty, not their cognitive skills. The story of a dog who refuses to leave his dead master's grave turns up in ancient Greece, in the Roman Empire, and in 19th-century Scotland, where "Greyfriars Bobby" became an Edinburgh institution. He left his graveyard vigil every day at 1 o'clock to get lunch at a nearby eating house, where crowds of tourists would gather to wait for him. Some hardheaded Scots suggested that it was the free lunch, not the graveyard, that Bobby was loyal to, but this kind of cold logic did not keep the dog from being the memorialized with a statue, numerous books, and eventually a Disney movie.

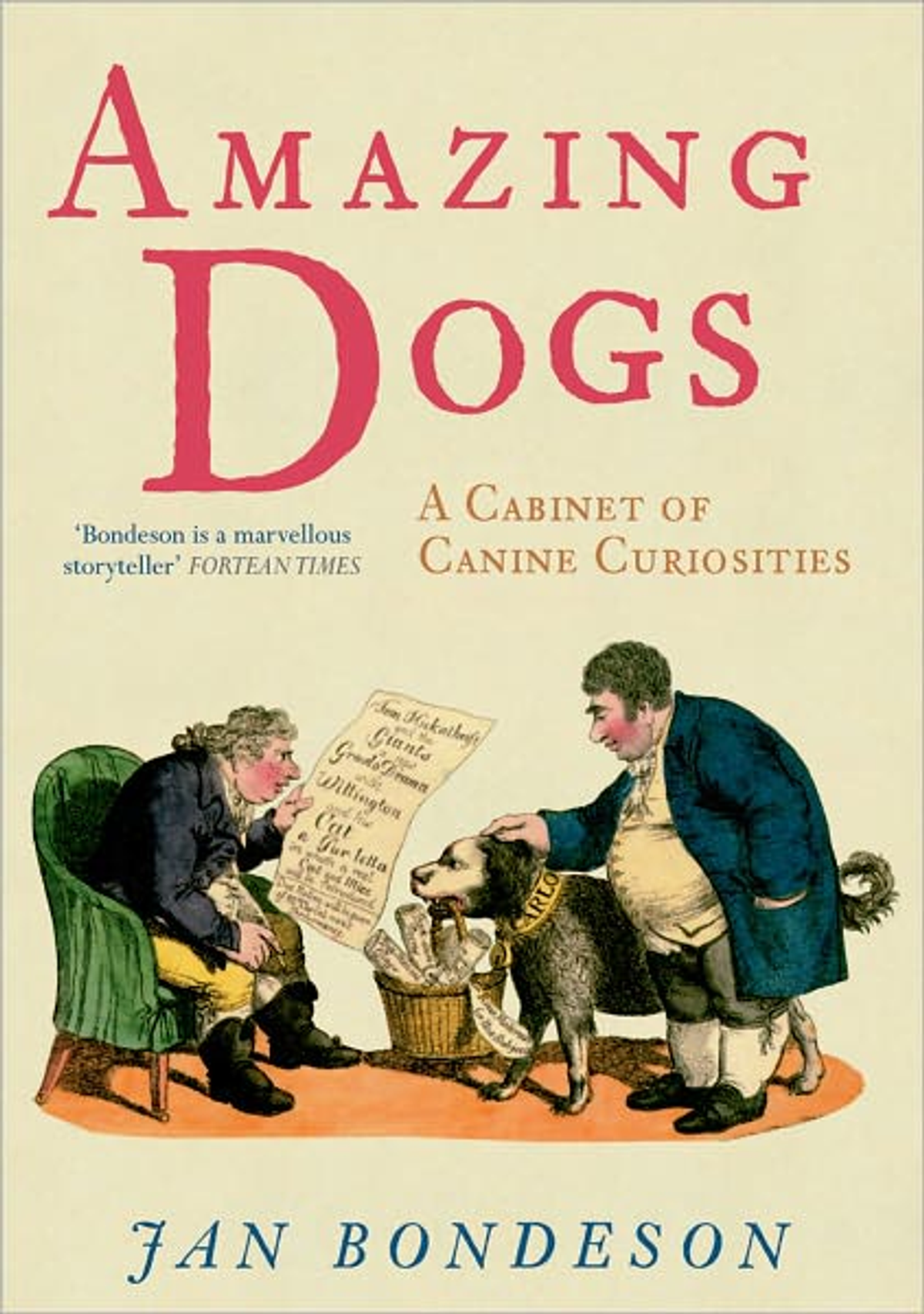

Sadly, Bondeson shows, there is usually a non-amazing explanation for such doggish feats. As with mind readers and faith healers, talking and counting dogs usually owe their powers to clever training and a willing suspension of disbelief on the part of the (paying) audience. More fascinating are the chapters of "Amazing Dogs" that deal with the actual ways dogs have been trained to serve human beings, through the long millennia of our species' co-evolution. Take the turnspit dog. In the Middle Ages, keeping a roast turning at an even pace over an open fire was hard, tedious work; so cooks would often employ a short, squat dog to turn a wheel attached to the spit, hamster fashion. These wheels were usually suspended from the kitchen ceiling or attached to a wall, and the book's engraving of a turnspit dog in action looks like something out of Monty Python. But these dogs were 100 percent real -- as were the Saint Bernards who rescued lost travelers in the Swiss Alps (though they didn't carry little barrels of brandy around their necks), and the dogs trained by the Paris police to rescue suicides from the Seine, and the dogs employed at British train stations to carry collection boxes for charity. After reading this very entertaining book, it starts to seem that the most wonderful thing about dogs is their patience with all the odd things we make them do.

Shares