My theme today is lost, forgotten or you might say misplaced designers. Why does a designer or illustrator, or anyone for that matter, at the top of his or her profession disappear from view? There are many answers, really -- some are quite simple: growth, midlife crisis, death, to name a few. Sometimes these people haven't really disappeared at all but for various reasons they are just not as visible, active or busy as they once were. My job is to find missing or lost persons.

My theme today is lost, forgotten or you might say misplaced designers. Why does a designer or illustrator, or anyone for that matter, at the top of his or her profession disappear from view? There are many answers, really -- some are quite simple: growth, midlife crisis, death, to name a few. Sometimes these people haven't really disappeared at all but for various reasons they are just not as visible, active or busy as they once were. My job is to find missing or lost persons.

The designers I have chosen to present in this new occasional series should not be considered entirely lost. For each has made a significant individual contribution to the general practice and to their specific clients. Each one has also had an influence on others in the field. Maybe you've heard of, or have seen the work of, at least one of the forthcoming subjects. The first is Gustav Jensen. Others will follow over the next few months.

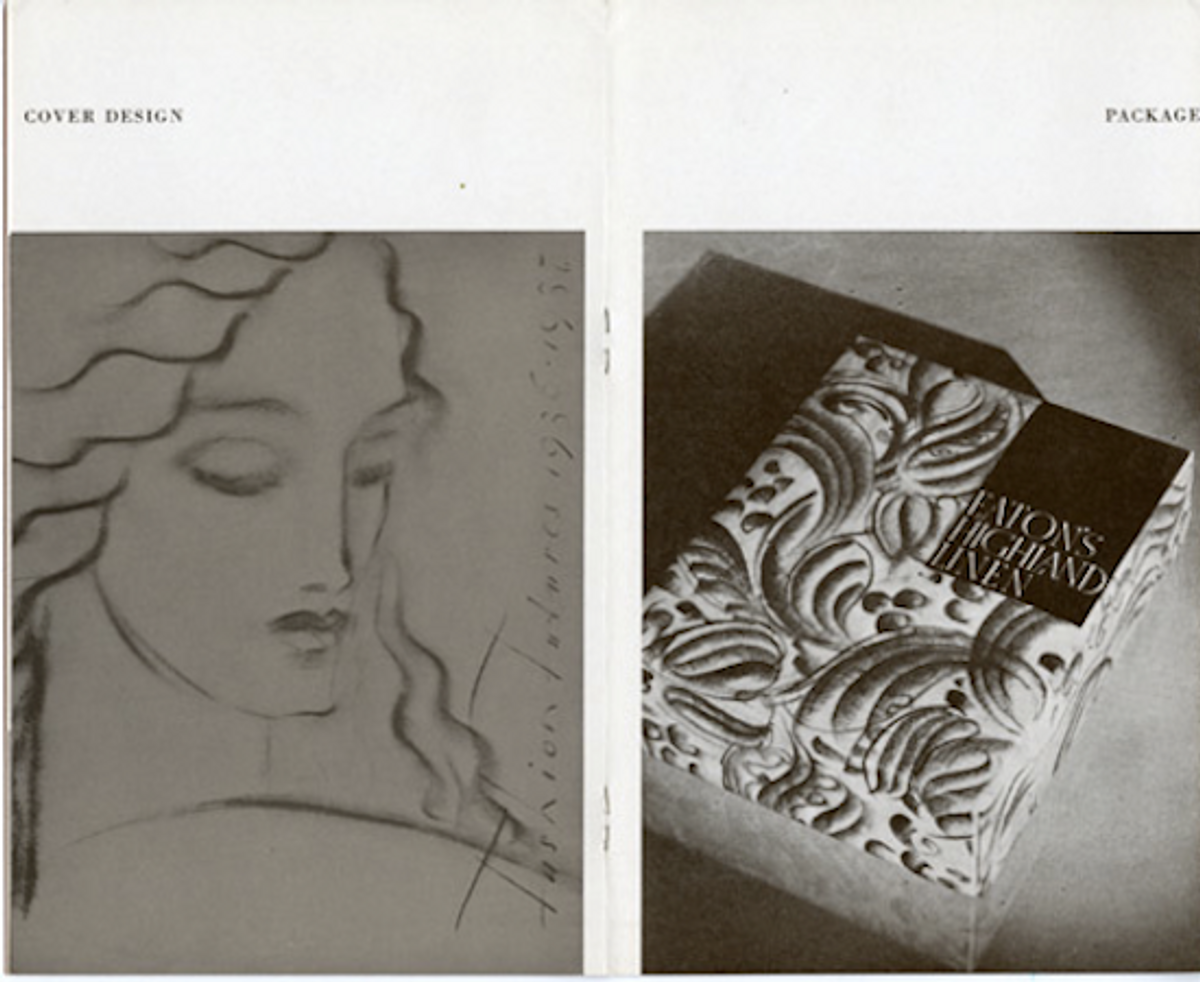

GUSTAV JENSEN called himself a Designer to Industry, and indeed he designed some of the most appealing packaging and advertising of the late '20s and early '30s. His most enduring was the package for Golden Blossom Honey, which has had virtually the same label for over 50 years. He was called the "Designer's Designer" by his peers, including Paul Rand, who in his early 20s tried to get a job at Jensen's one-man studio, and also borrowed from Jensen's contemporary beaux arts style on a few occasions before developing his own distinctive point of view.

Yet enigma shrouds Jensen's life. He is known to have been born in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1898; his father was a banker and lawyer, and his mother came from a long line of ministers. He studied philosophy at the University of Copenhagen, but with his deep bass voice he wanted instead to become an opera singer. He developed an interest in architecture, however. And architecture somehow led to an absorption in art, and art caused him to pursue aesthetic beauty in typography and printed design.

In 1918 at the age of 20 this 6-foot-5 "Dane Baso"arrived in New York and quickly became a designer of letters, borders, perfume bottles, cosmetic boxes, telephones, radios, silverware and kitchen sinks. Some who knew him insist that he taught an industrial design class at Pratt Institute, while others swear he never taught at all. There is evidence to prove that his work -- both fine and applied art -- was exhibited at the Metropolitan, Brooklyn and Philadelphia Museums, but none of these august institutions have any record of such events or holdings. Though he advertised his talents in the journals of the day, and accordingly received numerous commissions, he was not a self-promoter, like the other flamboyant "designers to industry," Raymond Lowey or Norman Bel Geddes, who preferred a streamlined aesthetic. Nor did Jensen provide ephemeral, fashionable coverings to industrial manufactures like these other designers.

But Jensen did produce a large body of work for companies like General Motors, Westvaco, Dupont, Edison, American Telegraph and Telephone, Morrel Meats, Gilbert Products and more. He brought a special elegance to a marketplace obsessed with fashionable conceits. Though making purely functional merchandise was not his primary concern, Jensen believed that the designer had a responsibility to provide the public with appealing products. "The public," he said, "is being imposed upon all the time, given stones for bread: The kind of bread we artists can give the public is hard sincere work straight from ourselves. Never mind what the style racketeers say."

Jensen's approach was decorative but not overly ornate. His work is characterized by economically applied textures derived in part from the Weiner Werkstatte (Vienna Workshop) and the Glasgow School whose products were imported through Danish retailers. Jensen was neither a proponent of the modern nor the moderne: He did not believe in functionalism. Utility, he said, is what designers begin with. The useful tools of civilization come first and then beauty is added. If a thing is to satisfy modern man, it must be beautiful as well as useful. But for Jensen beauty could be separated from function and simply please the mind and all its mysterious senses. Advertising, he suggested, is only useful when it is beautiful, and Jensen took great pains to see that the many small newspaper ads that he designed were eye-catching in the most provocative ways. This aesthetic requirement is apparent in much of the work -- even the everyday packaging -- you see before you.

Jensen's process was based on elimination; his method was simple but exhaustive. It has been said of him that "he does not make one sketch only, he makes hundreds." Jensen's individuality is expressed as much in the visible style of his wares as in his overall approach as recalled by his friends and colleagues. One friend wrote about him this way: "Gustav Jensen has a grand vision. He is a man who has the courage of his own convictions. A lover of everything in nature, he is impatient with fakes, fads, and fashions; he is extremely sensitive to beauty that is noble and poetic; and he is a master of design."

In the 1930s his packaging filled the annuals. But during the war-torn 1940s, owing in part to a manufacturing moratorium of non-essential goods, he was under-utilized. Nevertheless he continued as a one-man studio, making design and sculpture until he died in the early 1950s.

(Illustrations are taken from Marquardt's "Design & Paper XII" devoted to Jensen (c. 1938)).

Copyright F+W Media Inc. 2011.

Salon is proud to feature content from Imprint, the fastest-growing design community on the web. Brought to you by Print magazine, America's oldest and most trusted design voice, Imprint features some of the biggest names in the industry covering visual culture from every angle. Imprint advances and expands the design conversation, providing fresh daily content to the community (and now to salon.com!), sparking conversation, competition, criticism, and passion among its members.

Shares