With the final mission of the space shuttle looming on Friday, NASA puts a lid on five decades of U.S. space exploration with nary an ace left up its sleeve. Let's face it, hitching future rides out of a launch facility in Kazakhstan doesn't constitute a program so much as a glorified car service. And while some enthusiasts might feel a bit of a black hole each time they look skyward, I only need glance at the upper corner of my computer monitor to experience a sense of loss.

For the last 25 years, from the time I landed my first job out of college in 1986, the year Challenger went go at throttle up and then went no more, a small, bendable astronaut named Major Matt Mason has been perched atop my display.

Rescued long ago from the attic of my parent's house on Long Island, not five miles from the Grumman Aerospace Corp., where the Apollo Lunar Module was built and where my father spent his days scrawling bizarre math figures resembling hieroglyphics on chalkboards located inside buildings I was rarely allowed to visit ("What do you do, Dad?" I once asked, and he replied, helpfully, "You wouldn't understand."), this little action figure -- never call it a doll -- has always been within reach.

His blue eyes fading under cracking paint, his rubber arm dangerously close to amputation, Major Matt looks down at me as I type, though lately I'm the one staring back wistfully. STS-135 may be the end of an era for NASA -- for physicists, aeronautical engineers and tens of thousands of other folks who scored 800 on their math -- but it's the end of the line for us non-science space pretenders as well: those of us who don't know their yaw from their pitch, who get nervous just hearing words like "geosynchronous orbit," yet whose childhood is inextricably tethered, like Billy Mumy in the opening credits of "Lost in Space," to all things astronaut.

Like so many other 7-year-olds in 1969, I wanted to be tethered to a capsule, too, right up until the day I rode the Long Island Rail Road into New York City with my grandfather, who, after opening some accounts at Republic Bank and securing some free toasters, took me to the top of the Empire State Building. Couple my newly discovered acrophobia with another crippling disease for a fledgling astronaut, not having a single scientific bone in my body, and my space years were numbered before they ever began.

But it's impossible to have grown up near Bethpage, N.Y., during that time -- in the shadow of Farmingdale's Republic Aviation, builder of the mighty P-47 Thunderbolt, and a stone's throw from Roosevelt Field, site of Lindbergh's takeoff, and, most importantly, in a place that served as the universal answer to any local elementary school career-day question: What does your father do? He works at Grumman -- and not come out the other end a space geek. On my block alone, two kids, not one, were building futuristic hovercraft in their garages. Paging Steven Spielberg.

That's why this English major remembers what doomed Apollo 1 on the launch pad (the capsule was pressurized with pure oxygen), knows what the title of Michael Collins' lunar memoir was ("Carrying the Fire"), and can still name with ease the original seven Mercury astronauts. Two C's, two G's and three S's, my mental cheat sheet still at the ready. (Glenn and Grissom are easy, but the last "S" is a guaranteed trump card, as few people ever come up with Deke Slayton, and fewer still know that while even though he never flew a Mercury mission, Slayton finally got his chance in 1975 during Apollo-Soyuz.)

Aerospace so dominated life on Long Island that if you said you were from Bethpage, not a single person asked about the Black course or golf -- only Grumman. The Black, host to two recent U.S. Opens, was in a bit of disrepair then, and thought of, at least by the under-12 set, only as a good place to sled in winter.

Grumman, on the other hand, was bustling. From the legendary Hellcat and Wildcat, powerhouses of the Pacific, to A-6 Intruders of the Vietnam era, the company was a larger-than-life presence in my hometown. For years I dreamed about knowing what was behind all those guard booths that dotted the massive campus, or what kinds of planes were landing at the airstrip off South Oyster Bay Road, excruciatingly blocked from public view by jet blast deflectors. In Plant 3, work was under way on wings for Grumman's newest fighter, the F-14 Tomcat, the plane Tom Cruise would one day make into a sex symbol. Plant 5 was where the LEM was being built, the craft that would literally save the Apollo 13 astronauts and ensure Grumman's place in space history. And deeper off Stewart Avenue, Plant 26, the computing sciences/artificial intelligence lab, where my father worked on his ... well, I don't have a clue.

Somehow all of this filtered down to us kids, the ones destined for MIT and the ones destined for Chaucer. Wearing the uniform of the day, plaid shirt matched with pants of long vertical stripes, I perused and re-perused the Estes model rocket catalog in bed, spending my allowance on spacecraft with names like Big Bertha and Citation. Painstakingly gluing and painting these rockets in a basement with no ventilation ("Is the window open?!?" my mother would yell down. "Yessssssss!!" I'd yell back, though in reality the basement window, with 20 bent, rusty nails going in every direction, would have required a regiment to open it), I watched as some of them actually attained altitude, though just as many got toppled by the wind moments before liftoff, taking healthy divots out of the Old Bethpage Grade School baseball diamond.

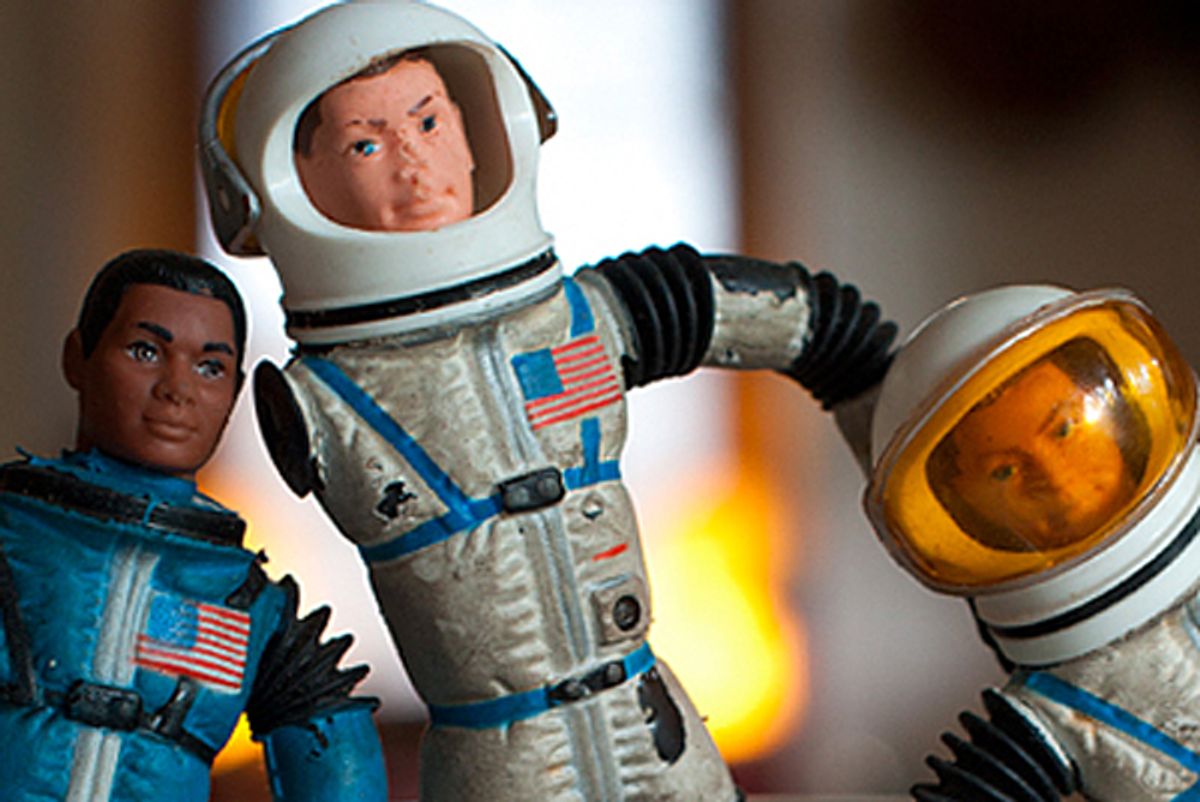

But more than anything else, we played with Mattel's kid-toy masterpiece, Major Matt Mason, a 6-inch rubber astronaut figure wearing a helmet with an orange visor. Tom Hanks is an unabashed Matt man, and astronauts over the years have been rumored to have taken him into space with them. I used to pretend that he -- me -- was trapped with Penny Robinson, of the "Lost in Space" Robinsons, on the rocky surface of Alpha Centauri. I spent hours jury-rigging those flimsy arms, so much so that my playroom sometimes resembled astronaut triage -- visors from other Matt Mason characters like Sgt. Storm being affixed to Doug Davis; legs from Lt. Jeff Long, an African-American astronaut action figure decades before a real-life one ever flew, attached to Major Matt. (Nowadays, Transformers and Bakugan toys regularly feature 379 pieces to potentially lose; Matt was as simple as they come.)

Four decades later, Major Matt has survived countless cleaning ladies, the occasional leaky ceiling, and many a move, when he and his rubber brethren are thrown back into their Satellite Locker, a vinyl carrying case I got as a consolation prize after my brother broke my arm in 1970, and carted off to a new base of operations.

My broken arm. My older brother Daniel snapped it while we were wrestling, and he wrote about the incident in a 2006 memoir about the Holocaust, of all things. To him, it was a metaphor for fraternal estrangement, for the distance between two young siblings -- one who cared about model rockets and the other who would occasionally dress as an Egyptian pharaoh. But I saw past the cruelty then, and I see past it now. To me that broken arm was one of the great moments in my life. Without the fracture, my father, who is not an effusive gift-giver, might not have taken me to the five-and-dime and let me pick out any toy I wanted. And I went for the Major Matt Mason Satellite Locker.

The space program is grinding to a halt this week -- no more T-minuses, no more astronaut walk-outs, no more boring but glorious shots of CAPCOMs hovered over computer screens. My link to it is long gone, too. My dad retired ages ago and Grumman was bought by Northrop in 1994, her Bethpage buildings reappropriated for other uses by other companies. The airstrip was built over, and cavernous Plant 5 is now a fledgling movie studio. I hear parts of "Salt," with Angelina Jolie, were filmed there. Everywhere else, as far as my memory is concerned, tumbleweed might as well be blowing.

But Major Matt Mason lives on. Last month Tom Hanks announced a deal to make a big-screen movie about my favorite little action figure. But while a Hollywood movie ensures that a new generation of kids will come to know Major Matt, I kind of want him to myself, sitting up there on his perch above my monitor, that right arm forever waiting to break, just as mine did 41 years ago.

Shares