In early November 1861, an American warship intercepted the Trent, a British mail packet, and forcibly removed two Confederate commissioners bound for London and Paris seeking to secure recognition of the upstart state. Tempers flared on both sides of the Atlantic as Washington protested the commissioners' use of a British ship to run its naval blockade, and Britain protested American interference with its shipping. Britain went so far as to send troops to Canada to signal its unhappiness.

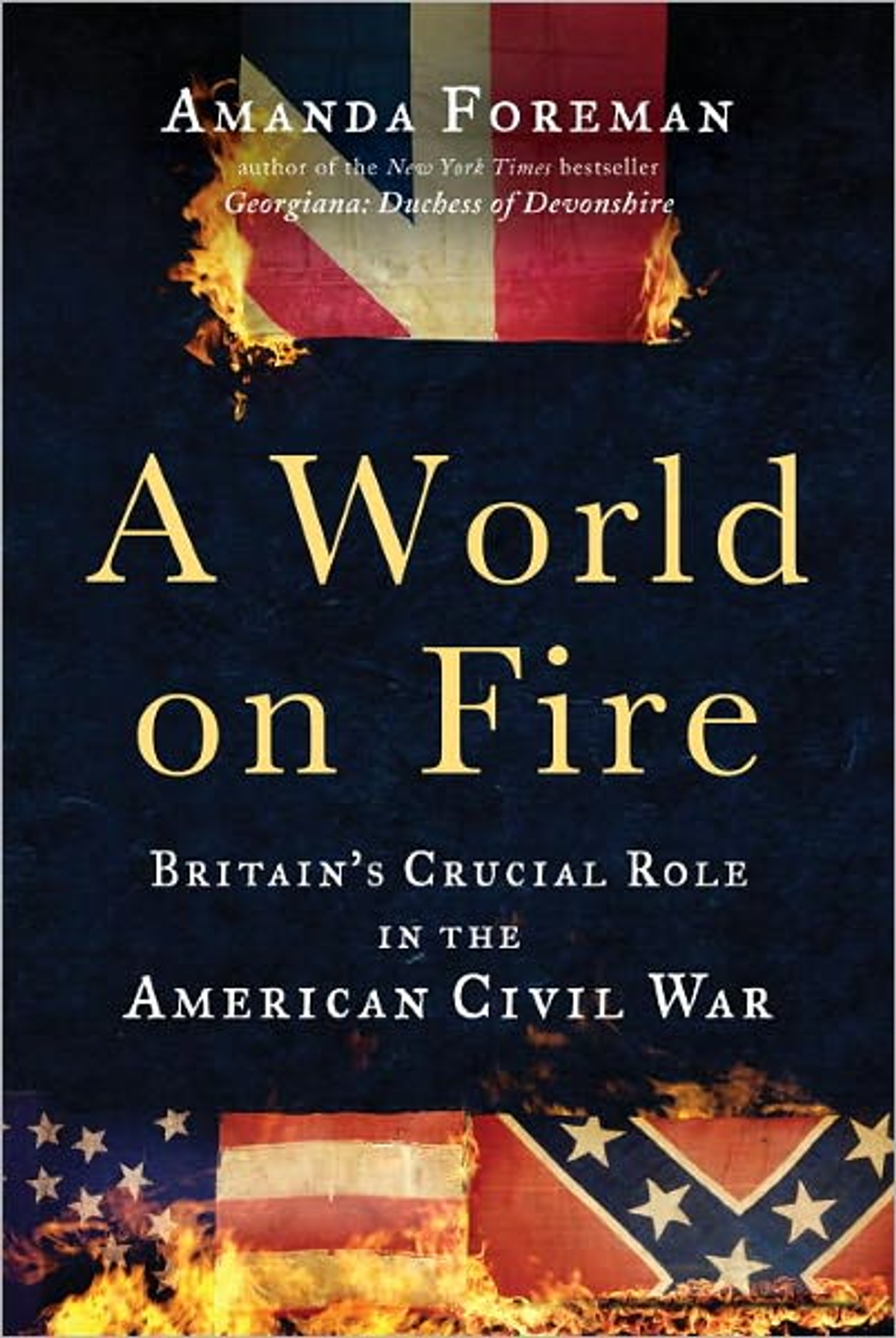

The Trent Affair, as it came to be called, was the closest that Britain and the United States came to engaging in armed conflict during the American Civil War. Amanda Foreman's new book, "A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War," chronicles, in a dramatized narrative, how the cataclysm of 1861-1865 pulled at and frequently strained the delicate threads that bound together the two former foes.

The Trent Affair, as it came to be called, was the closest that Britain and the United States came to engaging in armed conflict during the American Civil War. Amanda Foreman's new book, "A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War," chronicles, in a dramatized narrative, how the cataclysm of 1861-1865 pulled at and frequently strained the delicate threads that bound together the two former foes.

Foreman dazzled readers more than a decade ago with her biography of "Georgiana: Duchess of Devonshire." While researching that book, she was shocked to discover Georgiana's great-nephew, the heir apparent to the dukedom of Devonshire, had spent Christmas day 1862 making eggnog for Robert E. Lee's Confederate troops. In setting out to decipher what caused Britons to volunteer to fight, particularly for the slave-holding South, Foreman found herself telling not only the story of British volunteers, but also the larger story of Anglo-American relations.

In order to do so, she has assembled an array of famous names suitable for a lavish costume drama: Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope and Louisa May Alcott all make appearances, as well as Civil War stalwarts Abraham Lincoln, Stonewall Jackson and Ulysses S. Grant. As a reader, you know you're in for a cavalcade when a "dramatis personae" comes before the first chapter. Lords, ladies, and bureaucrats stride through the book, along with doctors, writers, spies, nurses, actors, sailors, admirals, generals and colonels. It would be tempting to call this novel-history hybrid Dickensian, but it is really more Tolstoyan in its scope as it moves between ballrooms, legations and battlefields.

The strongest narrative threads in the book follow not the British volunteers, but the diplomats. In Washington, William Seward pursued his job as a secretary of state with a zeal Machiavelli would relish, only to sabotage his own efforts with bellicose remarks that raised eyebrows in Whitehall. Lord Lyons, the British envoy (whose good-natured manner Foreman sets up as a foil to his surly American counterpart), constantly worked to downplay Seward's pronouncements with his Foreign Office colleagues. But when the Union got too high-handed with its treatment of British shipping, it was Lyons who had to impress upon Seward the importance of Britain's rights as a neutral. (Threatening to recognize the Confederacy now and then was one tool the British used to influence American policy.) Lyons and his staff also devoted an inordinate amount of time during the war helping British subjects strong-armed into service by both the Union and the Confederacy.

In London, Charles Francis Adams, the son of John Quincy Adams and American envoy to the Court of St. James, scrambled to keep Britain from falling under the spell of the Confederacy. Henry Adams, his son and informal secretary, tried to navigate the treacherous waters of the London Season, while fending off the sniping of Benjamin Moran, the legation's assistant secretary. Lord Russell, the prime minister, steered Britain on a neutral course, a difficult task when public opinion swayed between Blue and Gray -- depending on the latest reports off the boats.

Meanwhile, Confederate agents also waged a P.R. campaign that would turn Don Draper green with envy. Russell, however, would not let sentimental feelings for the South or pressure from the "cotton lobby" swamp the reality that British recognition of the Confederacy would lead to war with the Union and jeopardize British control of Canada and the Caribbean.

Journalists also play a large role in Foreman's book, providing colorful eyewitness accounts to key battles. The book is sprinkled with illustrations from the period, many created by Frank Vizetelly, the talented, hard-drinking correspondent for the Illustrated London News. The reporters sent by British newspapers to cover the war tended to favor the South and spent much of their time with Confederate troops. Their rosy accounts helped to fuel the British public's sympathetic view of the Confederate cause.

In the book's prologue Foreman says that she wanted to write "a biography of a relationship, or, more accurately, of the many relationships that together formed the British-American experience during the Civil War." Using the tools of a biographer, she adeptly marshals letters, journals, documents, and newspaper accounts to bring to life the men and women who populate her tale. But in the end, despite the vast research and lively writing, the book amounts to a series of well-rendered vignettes. Foreman refrains from stepping back to provide a historical overview that would anchor her carefully rendered relationships in a larger context and to draw conclusions from them. Even a biography -- or a collective biography -- should have a point of view. Her reluctance to make an overarching argument leaves the assertion made by book's subtitle, "Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War," in doubt.

What Foreman has created is a sprawling 960-page chronicle of interconnections between two countries -- three if you count the Confederacy -- during one of the most tumultuous eras in American history. Connoisseurs of political gossip, intrigue and diplomacy will applaud as a cast of historic, and sometimes neglected, figures take their turn on a stage of epic proportions.

Shares