On Saturday, July 9, the world’s youngest sovereign state -- South Sudan -- was born. South Sudan is the 34th country to join the United Nations since the Soviet Union dissolved 20 years ago. In the years ahead, more new nation-states will emerge from the ruins of disintegrating multinational entities cobbled together by dead empires -- and overall, that’s a good thing.

Call this trend the Second Decolonization. The first decolonization followed World War II, when the U.S. and the Soviet Union pressured Britain, France and other European countries with overseas empires to liquidate them as quickly as possible. Both superpowers were creedal states whose creeds included opposition to imperialism. Both superpowers hoped to win support among Asians, Africans and Middle Easterners by supporting their aspirations for independence. And the U.S. sought access to colonial markets long closed to American exports.

Although President Franklin Roosevelt had hoped for a gradual process of decolonization under U.N. trusteeship, demands for independence and Cold War politics produced a rapid hand-over of power from European countries to their former subjects by the 1970s. To avoid the chaos that would follow from an attempt to redraw borders to make them fit ethnocultural communities, the international community favored the quick-and-dirty solution of making former colonial internal administrative borders the official borders of newly independent states.

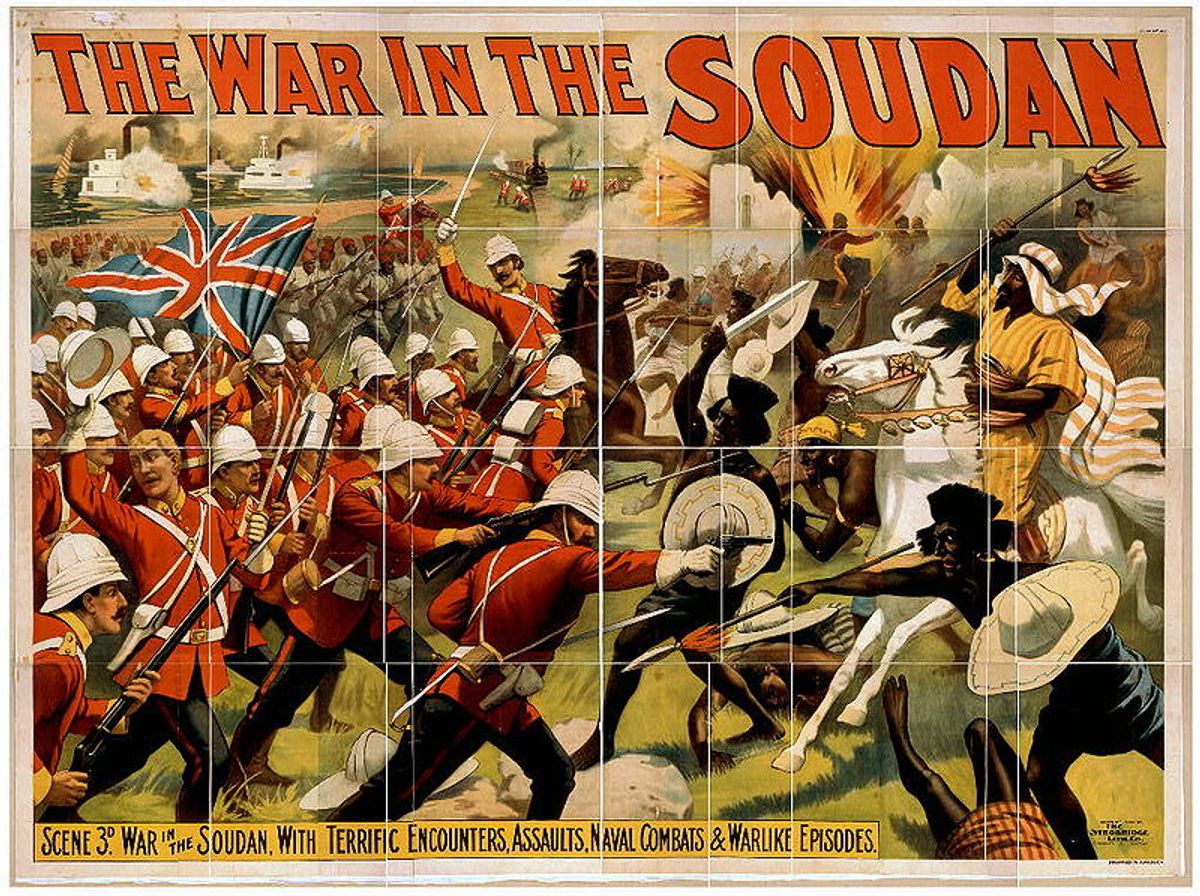

The problem with this approach was that colonial borders in much of Africa, Asia and the Middle East did not correspond to peoples. Countries like Pakistan, Nigeria and the former united Sudan were completely arbitrary creations of European or Soviet colonial administrators. Sometimes the borders were drawn as part of a cynical divide-and-rule policy by the empire, with the purpose of splitting ethnic groups or pitting them against one another, to ensure that each would appeal to London or Moscow.

From Sudan to Afghanistan to Kashmir to Israel/Palestine to Cyprus, the British imperial legacy in particular poisons 21st century world politics. Sudan was a British creation, roping in black Christians in the South with Arab Muslims in the North who tyrannized them until they seceded.

Another British legacy was the Durand Line drawn by the British in 1893, which became the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. American soldiers, fighting and dying in a war in Afghanistan that is more against Pashtuns on both sides of the Durand Line than jihadists, have stumbled into the ethnopolitical equivalent of a century-old minefield.

During the Cold War, the liberal West and communist East alike feared that conflicts over aligning territorial borders with peoples would draw in the superpowers. The test came in 1967, with the attempted secession of Biafra from Nigeria, another arbitrary creation of the British empire. The UN and the western powers including the U.S. supported the central government, halting what might have been a second wave of decolonization throughout the post-colonial world. Because Africa’s post-imperial countries are the least culturally coherent, the rule of the sanctity of borders established at the time of independence from European rule benefited their rulers -- disproportionately soldiers and kleptocrats who hold their miscellanies of ethnic groups together by force and nepotism.

When the Cold War ended, the inhibition against redrawing borders to fit peoples relaxed, both in the case of reunited nation-states like Germany and Yemen and partitioned multinational states like the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia and now Sudan. Long after the Berlin Wall fell, however, America’s foreign policy establishment, which has an occupational bias toward threat-inflating alarmism, continued to warn that any attempt to fix borders would be the Sarajevo-like incident that could spark a world war. In his infamous “Chicken Kiev” speech, President George H.W. Bush warned the Ukrainians and other Soviet nationalities who shortly thereafter obtained their independence not to secede from the USSR.

But the Soviet Union dissolved with far less bloodshed than many expected, and when NATO intervened in the Balkans in the 1990s it was to ratify the division of Yugoslavia into (at latest count) seven new countries, not to put Humpty Dumpty back together again. Subsequently under George W. Bush and Barack Obama the U.S. blundered into “nation-building” conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya where the local populations tend to be loyal to their tribes, not to territories created by dead Europeans.

South Sudan proves that partition beats nation-building, in countries where there are no nations to be built. A few years back, trigger-happy “humanitarian hawks” of the kind who have cheered on the unnecessary American war against Libya led a children’s crusade of college students on campuses across America to demand U.S. military intervention in Sudan. Had they prevailed, the U.S. might now be bogged down in a fourth military quagmire in the Muslim world, trying to hold the “nation” of Sudan together by force, instead of supporting the independence of the newly seceded republic of South Sudan.

A persecuted ethnic minority in a crumbling multi-ethnic regime is usually better off obtaining its own sovereign state, with its own military, as an alternative to becoming the wards of foreign protectors like the U.S. military or the UN Blue Helmets. The international community is far more opposed to cross-border aggression than it is to massacres and ethnic cleansing carried out by one ethnic group against another within a single territorial state. That is why the states of the world, from Arab monarchies to communist China, virtually unanimously condemned Iraq’s attempted conquest of Kuwait in 1990, but did little to stop the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.

The replacement, preferably by peaceful means like popular referenda, of multinational entities trapping mutually hostile ethnic groups into cycles of ethnic violence by a greater number of smaller, more linguistically and culturally homogeneous nation-states protected by their own borders is a long-term global trend that should be welcomed by those who favor a peaceful and democratic world. The division of former multinational states into nation-states increases peace, because cross-border wars are much scarcer than intra-state ethnic conflicts.

Democracy, too, tends to function best in countries where there is a clear ethnocultural majority with a sense of common identity. This contradicts ritual incantations that the U.S. is successful because it is a “proposition nation” composed of immigrants who share nothing in common except territorial borders and a written constitution. But in fact the American nation-state is far less diverse than it seems.

Most Americans are monoglot English speakers. Immigrant diasporas tend to lose their languages and all but a residual identity after a generation or two. Despite nativist nightmares of a “Hispanic Quebec” in the Southwest, Latino immigrants are assimilating at the same rate that European immigrants once did. The deepest racial division in the U.S. is between black and white Southerners, who, if the truth be told, are merely separate castes of a single Southern community, with virtually identical religious views, accents and customs. States’ rights ideology still shapes the American Right, but no significant faction has supported territorial secession from the U.S. since the Late Unpleasantness of 1861-1865. America may be multicultural, but it is not multinational.

In any case, there is no real comparison between nation-states like the United States that welcome and assimilate voluntary immigrants and former colonial territories in Africa, the Middle East and Asia that contain several millennia-old nationalities within their artificial recent borders. The only multinational states that have been successful democracies are those with elaborate ethnic power-sharing systems based on quotas and group rights, like Switzerland, Belgium and Canada. Perhaps such complex, quota-driven systems can hold multi-ethnic countries like Bosnia and Herzegovina, Iraq, Afghanistan and South Africa together indefinitely. But to stay together, these multinational democracies require that the democratic ideals of individual rights and one person, one vote and geographic mobility be sacrificed forever to ethnic rights and ethnic brokering and official ethnic homelands.

Will the 30 million Kurds one day obtain their own, long-deferred Kurdistan? Will the 40 million Pashtuns on the two sides of the Durand Line in Pakistan and Afghanistan create Pashtunistan? Except in cases where there is a vital American interest, the U.S. should remain neutral in the secessionist conflicts of the Second Decolonization. Fortunately, now that more than two dozen new countries have been born in fewer than two decades, at the cost of temporary local violence in some cases but not World War III, overblown fears of instability appear to be fading. With them is fading the American establishment’s left-over Cold War habit of reflexively opposing all partitions of unworkable multinational states into nation-states.

Around the world, the principle of popular sovereignty has been trumping the dubious sanctity of empire-created state borders. Americans have reason to be proud. The American Revolution was, after all, the first modern secession movement that broke up a multinational state in the name of the sovereignty of a people.

Shares