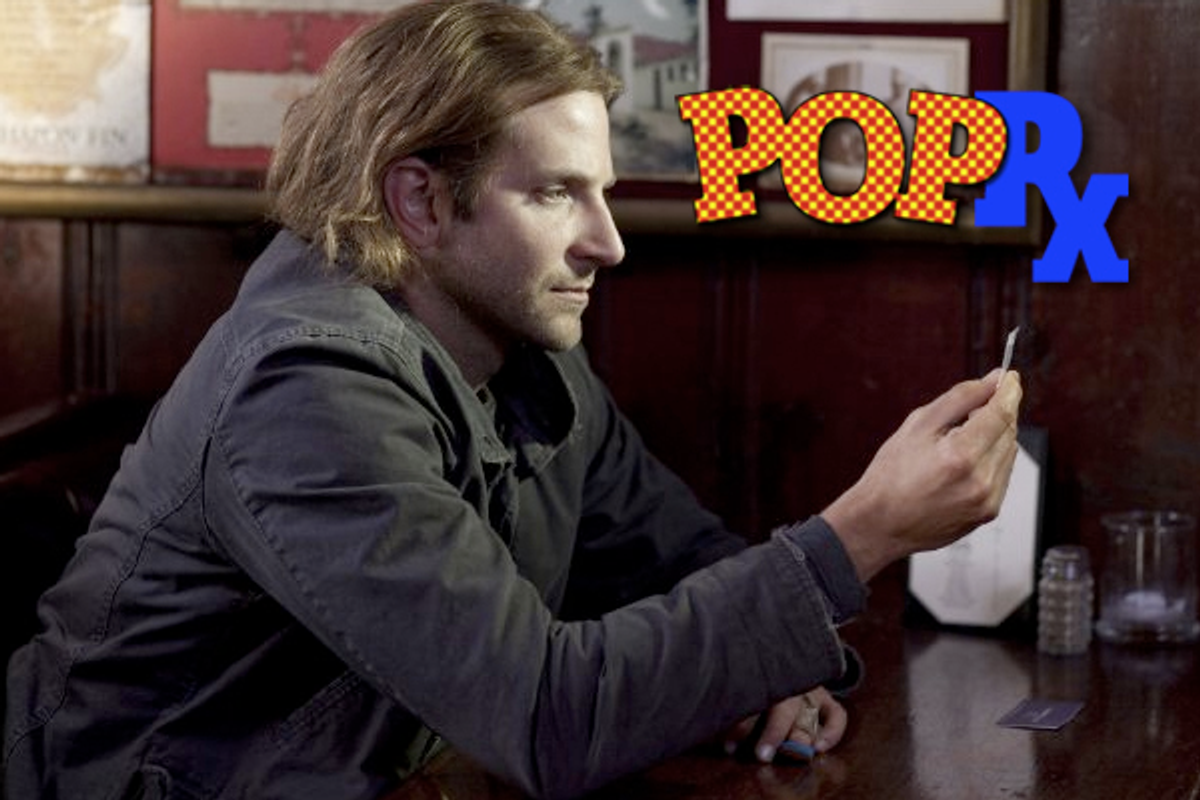

The movie "Limitless," which came out on DVD last week, presents a potential future fueled by designer drugs. When we meet the film's protagonist Eddie Mora (Bradley Cooper), he's a divorced, disheveled, socially awkward writer who can't even come up with the first words of his novel. After getting dumped by his girlfriend, Mora runs into his drug-dealing ex-brother-in-law who offers Eddie a solution in the form of a little round pill. Within minutes, the drug transforms Eddie into a brilliant, creative, driven alpha male who quickly and effortlessly completes his long-stalled book.

"Enhanced Eddie" then acquires a stash of these pills and, in rapid succession, cleans himself up, learns Italian, wins back his ex-girlfriend and becomes a celebrity investment banker.

The film's "miracle" drug may seem far-fetched, but it's based in a medical reality: Taking certain medications, specifically those developed to treat psychiatric and neurological disorders, can boost cognitive performance in otherwise healthy people.

Many of us instinctively recoil from such an idea for moral reasons. Sculpting our brains, unlike, say, sculpting our noses, seems like cheating. But consider this: 7 percent of surveyed college students (and some 25 percent of those on elite campuses) have taken an unprescribed Ritalin -- or a similar drug used to treat attention deficit disorder -- to boost their performance on an exam.

And the phenomenon is not restricted to college students trying to raise their grade point averages: The military has a history of encouraging -- and sometimes even ordering -- soldiers to take Ritalin or Provigil, a drug that boosts alertness. Canadian researchers are now looking at a drug called metyrapone that may help dull the sting of painful memories. Already common is the number of executives who swallow a little dose of Propranolol -- which is normally used to treat high blood pressure but has also been prescribed for performance anxiety for many years -- to calm their nerves before they speak. And with so many of us already hustling to Starbucks morning, noon and night for shots of caffeine to keep us going, the question arises: Is there a case to be made for cognitive enhancement?

A few years ago, a distinguished group of scholars claimed there was in an essay in Nature:

Human ingenuity has given us means of enhancing our brains through inventions such as written language, printing and the Internet ... And we are all aware of the abilities to enhance our brains with adequate exercise, nutrition and sleep ... drugs ... should be viewed in the same general category as education, good health habits, and information technology -- ways that our uniquely innovative species tries to improve itself.

The writers proposed a series of principles that would help society regulate these drugs responsibly and fairly. These rules stipulated that any mentally competent adult would be allowed to use cognitive enhancing drugs, that professional organizations would develop policies for their prescription and use, that detailed research would be conducted regarding their risks and benefits, and that access to such medications would be provided regardless of socioeconomic status.

The authors correctly point out that "there is certainly a precedent for this broader view in certain branches of medicine." Lifestyle drugs like Viagra are an over $30 billion a year business. And then there are substances like caffeine and alcohol that we commonly use as lifestyle drugs -- to keep us up, to help us relax, to make us focus, to put us to sleep -- even if we don't think of them that way. There are also those of us -- myself included -- who take drugs we wouldn’t normally think of as lifestyle drugs and use them as such. If I’m going to drink a few glasses of wine over dinner, or have an extra cup of coffee to get through my day, I’ll sometimes pop a Prilosec so that I don’t wake up in the middle of the night with heartburn.

But taking a pill to get an edge for that job interview or ace that test is deeply unsettling. On a visceral level, the idea that we're "playing God" with our minds disturbs us. There's also the question of what happens to our sense of accomplishment. What does it mean if achieving your dreams merely means popping a pill?

There are two more concrete arguments as well. First, access to these mind-altering substances would likely (at least initially) be limited to those with the money to afford them. The authors of the essay in Nature try to allay this fear by suggesting, somewhat naively, that every exam-taker have free access to cognitive enhancements "as some schools provide computers during exam week to all students." But it's easier to imagine the society predicted by the President's Council of Bioethics in 2003, where we see "the emergence of a biotechnologically improved aristocracy. [This] is indeed a worrisome possibility, and there is nothing in our current way of doing business that works against it. Indeed, unless something new intervenes, it would seem to be a natural outcome of mixing these elements of American society: our existing inequalities in wealth and status, the continued use of free markets to develop and obtain the new technologies, and our libertarian attitudes favoring unrestricted personal freedom for all choices in private life."

Finally, we can't ignore any known and unknown risks of the side effects of cognitive enhancers. In "Limitless," we see Eddie become increasingly dependent on his drug, which leads him to visual hallucinations and memory loss. With Ritalin, we worry about sleep disturbances, high blood pressure, weight loss and emotional instability. With Provigil, there are concerns of visual hallucinations, insomnia and depression.

Of course, it's easy to make these judgments in the abstract. But what if, for example, your child needs a lifesaving but risky and complex 15-hour surgery? Wouldn't you want that doctor to be as alert as possible throughout the procedure, even if that meant using Provigil or another cognitive-enhancer? Or what if your son is on the ground in Afghanistan? Wouldn't you want him to be able to take a dose of Ritalin before going on patrol, so he’s sharp and ready to defend himself?

But regardless of your personal feelings on that matter, our ability to innovate will continue to challenge our sense of morality. We can't simply pretend that these drugs don't exist. The writers in Nature deserve credit for being willing to start this conversation. Still, for all of their logic, their biggest fault is their dismissal of the role of human hubris and ambition. Perhaps Eddie Mora says it best: "There are no safeguards in human nature. We're wired to overreach."

Shares