When Barack Obama used a press conference late last Friday to once again embrace cuts to Medicare and Social Security as part of a debt ceiling deal, he noted that Nancy Pelosi "sure did not like the plan that we are proposing."

Can you blame her? Forget about whatever philosophical objections she might have to reducing entitlement spending: Obama's posture these past few weeks threatens to wipe out a 2012 campaign strategy that has the potential to deliver significant gains for Pelosi's House Democrats.

Let's remember how we got here. Three months ago, House Republicans handed Democrats a gift that seemed like it would keep on giving clear through the 2012 elections, lining up in near-unanimity behind a plan that would essentially reconfigure Medicare as a voucher program.

Speaker John Boehner, it was clear, embraced the Paul Ryan-authored plan not because he wanted to but because he believed he and his conference had to. Putting the House GOP on the record in support of a truly radical overhaul of Medicare and enduring the resulting abuse from Democrats and pundits, Boehner seemed to calculate, was necessary to show good faith to the GOP's Tea Party base. That base, after all, had revolted during the 2010 midterm primary season, knocking off seemingly entrenched GOP incumbents and candidates favored by the party establishment. And it would do so again in 2012 if Republicans on Capitol Hill didn't demonstrate that they had "purified" themselves ideologically.

So Boehner made the Ryan plan a major part of the GOP's agenda and when it came for a vote in mid-April, all but a few Republicans supported it -- and every Democrat voted no.

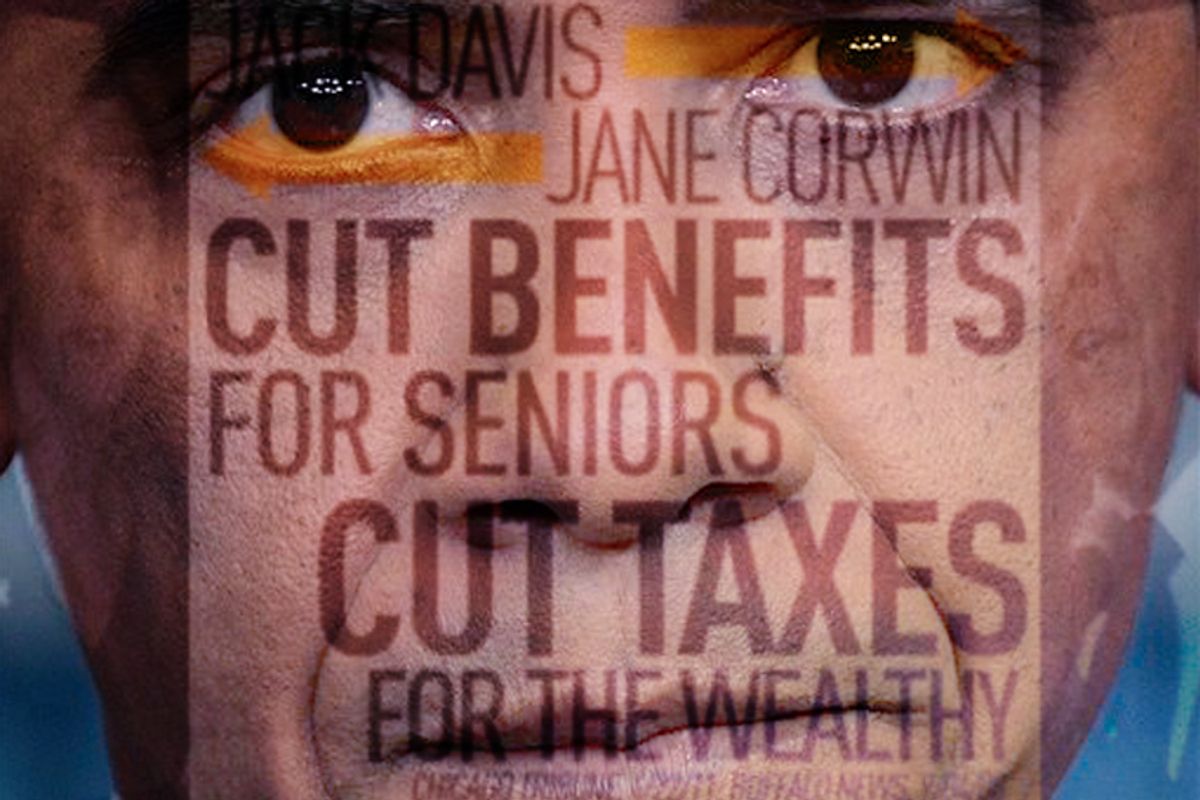

For Democrats, this offered a chance to recycle a game plan that worked well for them back in 1995 and 1996, the last time a new Republican majority took power in the House. Then, as now, the GOP targeted Medicare and Democrats made a show of fighting them, warning seniors about potentially catastrophic benefits reductions and using the issue to portray congressional Republicans as dangerously extreme ideologues. A variation of this ad was run by Democrats in virtually every competitive congressional district in the '96 campaign:

The result: Two years after the 1994 Republican revolution, 18 Republican incumbents were defeated for reelection. It wasn't enough to win back the chamber for Democrats, but it was clearly a successful strategy -- particularly in swing districts in the Northeast and the Rust Belt and along the Pacific Coast.

Not surprisingly, then, Democrats began dusting off that '96 playbook almost as soon as the Ryan plan cleared the House in April. And thanks to the unexpected resignation of Republican Rep. Chris Lee, they soon had an opportunity to test it out, in a special election in a GOP-friendly district in Western New York -- pretty much the kind of district that flipped to the Democrats back in '96. Kathy Hochul, the Democratic nominee, made Medicare the central issue of her campaign, with ads like this:

The result: A sizable victory for Hochul in the May 24 special election. Suddenly, the idea that Democrats might actually post the 25-seat gain needed to win back the House in 2012 didn't seem out of the question. At the very least, it seemed, they had found a winning issue sure to bring them within striking distance of control heading into the 2014 cycle.

But then came the "grand bargain." For the past several weeks, Obama has aggressively and publicly pursued a deficit-slashing deal with Boehner that, in exchange for relatively slight revenue increases, would make deep domestic spending cuts, even in Medicare and Social Security. The grand bargain now seems dead, but Obama has now provided an abundance of emphatic sound bites in which he makes it clear that he believes entitlement spending can and should be cut and that doing so would strengthen -- and not harm -- the programs. In other words, he has handed the GOP the tools to create the perfect response to ads like Hochul's during the '12 campaign.

The basic political logic behind Obama's move is obvious. As Ed Kilgore noted this morning, he is pursuing a reelection strategy that depends on convincing swing voters that he's a reasonable, compromise-friendly pragmatist -- and that the GOP is beholden to an irrationally ideological base. There are even those who believe Obama always knew the grand bargain wouldn't work, and that he pushed it so hard just to demonstrate how unwilling the GOP is to compromise.

Some liken this to the strategy Bill Clinton pursued in '95 and '96, making Newt Gingrich and the GOP Congress his enemy, but there's one key difference: Back then, Clinton and congressional Democrats were on the same page when it came to Medicare. Clinton refused to sign a GOP budget that cut Medicare spending by $270 billion, forcing a dramatic government shutdown instead. And congressional Democrats then used that showdown as the basis for their unrelenting Medicare attack ads. Obama, though, has now undermined his congressional party's Medicare message.

Does this mean he's destroyed his party's best chance of winning back the House next year? That's one possible interpretation. It's also possible that if Obama succeeds in defining the GOP as a fundamentally radical party and is able to win reelection on that basis that congressional Democrats will also benefit -- that an anti-GOP tide will lift in '12 even without the Ryan plan playing a big role. And, of course, it's also possible that, however the current standoff is ultimately resolved, the public's attention will quickly return to the weak economy and poor job growth and that voters in '12 won't end caring much about Medicare, the debt ceiling, or GOP extremism.

What is clear, though, is that Obama has made his party's strategy for next year's election a lot more complicated.

Shares