Who'd win in a fashion fight, the original Wonder Woman or Miss Fury?

Who'd win in a fashion fight, the original Wonder Woman or Miss Fury?

Well, one of them wears a headband, a bustier, a star-spangled skirt, and calf-high boots, all in bright, primary colors, which she often models in manacles. The whole ensemble is très tacky. And the other one vogues in the finest haute couture her creator can imagine, or lounges in satin and lace finery, in her "civilian" Marla Drake identity.

"Unfair fight!" you cry. After all, Fury's creator began her career as a professional fashion illustrator. And! During "Miss Fury's" first couple of years the heroine typically prowled around in a skintight, basic-black body suit with pointy little cat ears and panther-paw fingers and toes ... très silly.

OK, then: Who of the two was the very first on the comics scene? Well, the cover of the just-released "Tarpé Mills & Miss Fury: Sensational Sundays 1944 - 1949" touts Fury as "The first female superhero created and drawn by a woman cartoonist." But the truth is, she's also the first female superhero, period. Debuting in 1941, she beat out the Amazon princess -- who was created by a male bondage aficionado -- by six months.

Tarpé Mills & Miss Fury's 200 pages of newspaper reprints skip past those early "costume" dramas. Here the adventure opens mid-plot, as we're introduced to the treacherous vamp Baroness Erica Von Kampf -- yes, as in "Mein ..." And if that name isn't enough to cue readers about the baroness's allegiances, she also has a swastika branded on her forehead. Among the cast of outré characters is Charles Villon, another "Fury," uh, villain. Nicknamed "Whiffy," he's a ruthless gangster with a penchant for dressing in full drag. Whiffy also wears way too much perfume, a fact graphically indicated by wavy stink lines that emanate from his massive body.

The book's editor, Trina Robbins, has also earned several of her own "firsts." She was not only the first significant female underground comics artist of the 1960s, she was also a founder of the first continuing all-woman comic book, "Wimmen's Comix."

I also consider Trina to be one of the first third-wave feminists, ahead of her time during the movement's first wave, with her then-"politically incorrect" portrayals of women. She also distinguished herself by the clean, graceful lines of her art, which stood in marked contrast to the heavy, belabored renderings of most of her peers.

Trina now focuses her attention on the writing side of the comics biz. She's also a distinguished comics herstorian. Her "A Century of Women Cartoonists," from 1993, is a classic of its kind. And she followed it up with "The Great Women Cartoonists"and "From Girls to Grrlz : A History of Women's Comics from Teens to Zines".

When I was a program organizer for the popular -- and hotly controversial -- "Masters of American Comics" exhibition at L.A.'s UCLA Hammer Museum and Museum of Contemporary Art a few years ago, Trina was the very first guest speaker I recommended. Two reasons. First: her talks are inevitably fascinating and informative, and often provocative. And second: I felt that the exhibition's exclusive lineup of 15 male masters -- including Trina's personal bête noire, the noted misogynist Robert Crumb -- demanded that alternative perspectives be included in the program. And when I was assembling the 60-plus contributors to my "The Education of a Comics Artist" book, co-edited with Steve Heller, she was, of course, among my top choices.

Trina's 2009 "The Brinkley Girls: The Best of Nell Brinkley's Cartoons From 1913-1940" is a stunning collection as well as a detailed pictorial chronicle of the evolution of fashion and style, from Nouveau to Deco. And now she's added "Tarpé Mills" to her volumes of female comics masters. The publication of these books -- along with Trina's recent appearance at the annual San Diego Comic-Con -- seemed to me like a good occasion for some conversation.

During your underground comics days, you were called sexist because you drew beautiful women. What's your perspective on that era?

There was a lot of overreaction in the early feminist movement of the 1970s, as there is after every revolution. At least I was not guillotined or sent to a labor camp! I think things have calmed down a bit since those days.

And now you're writing biographies of female comics creators who featured glamorous gals in gorgeous gowns.

Yes! I love clothes. I love lipstick. I love glamour. And obviously, so have many other women, if you look at the large readership of artists like Nell Brinkley and Brenda Starr's Dale Messick. And in the case of younger readers, at all the girls who loved Katy Keene. There probably are still some women who might want to see me, if not guillotined, then at least sent off to a gulag for promoting such work.

Even I am a trifle alarmed at some of the stuff I see younger women wearing: heels so high that if they continue to wear them their feet will be crippled by the time they reach 50, or skirts so short that they are showing far more than they really intend to show.

Here's a fashion hint: If you have to tug your skirt down all the time, it is too short.

What was your personal attraction to "Miss Fury"?

I've always been a lover of noir and of good adventure strips in the noir mode, as typified by Milton Caniff's "Terry and the Pirates." They are adventures that are good, fun escapist reading. As you know, there were a number of cartoonists during the 1940s who worked in that genre, but only Tarpé Mills was a woman. That alone would have been enough to attract her to me. But add to that: good art, solid storytelling, memorable characters... including three of the strongest female characters in comics. Need I say more?

You mention in your intro that Mills' "woman's romantic fantasy" plots generated fan mail from girls. In what other ways did Miss Fury appeal to female readers?

Mills' characters also wore great fashions -- back to clothes again! -- at a time when many of the male cartoonists dressed their female characters in featureless red strapless evening gowns or equally featureless short red V-necked dresses. Of course there are exceptions -- Caniff was very up on women's styles. But I think in general one sign that a comic is by a woman is that attention is paid to the clothing -- Miss Fury, Brenda Starr, Mopsy, I could go on and on -- and that men tend not to show much awareness of what real women are wearing, even today... especially today!

And then, of course, an adventure strip in which the hero is a woman and some of the strongest secondary characters are women... yeah, women do like that. And they have since they read Nancy Drew, as girls.

Mills also drew cutout paper dolls.

Yes, the paper dolls were only in the comic book reprints, not in the newspaper strips, but I have a feeling that Mills also used them when replying to fan mail requesting art. I have paper doll pages that were probably printed up by the syndicate. She had that great sexy pinup of Marla half out of her cat suit, which she sent to the GIs. I think maybe if the fan mail was from a woman or girl, she may have mailed back the paper dolls.

In your book we mostly see Marla in dresses ... and lingerie. Was her panther outfit primarily a commercial concession to the times?

I adore those lacy underthings! Of course, we'll never know, but I think it's quite possible that the panther suit was a concession, like the Spirit's mask. Or possibly Mills liked the idea of the panther suit in the beginning, but later got caught up in the adventure of the storyline, which was more in the "Dick Tracy" or "Terry and the Pirates" mode.

.

Did the Whiffy character cause any public outrage, or were Chester Gould-ish villains fairly commonplace by then?

I have never seen anything that leads me to believe anyone was outraged by Whiffy. As you say, the public was used to grotesque villains.

The only outrage I have seen were those newspapers that censored Mills' strip in which she dressed her nightclub entertainer character, Era, in an outfit that would not bother us in the least today. But it obviously shocked the pants -- yes, verbal joke intended -- off some people.

Art by Tarpé Mills, red ink overprinting by the blue-nosed Boston Globe. 1946

"Miss Fury" was condemned to hellfire by Catholic Church crusaders, and one skimpy outfit was even "banned" in a Boston paper. Did actions such as this have any effect?

It may have caused some people to sit up at attention and start reading the strip, but I don't really know.

Mills enjoyed being risqué. You should see the get-well card she drew for her cousin!

Here's that card Mills drew for her cousin. Inset: cover.

The Baroness ... exposed! Art by Tarpé Mills.

Were there particular comics artists that Mills emulated?

We'll probably never know. But I think she was one of the many cartoonists influenced by Caniff ... and by Caniff's popularity.

What artists has Mills herself inspired?

Me! I've been scripting comics starring Honey West, who was the first female private eye on TV back in 1965 and '66, starring the beautiful Anne Francis. And I've been writing them in noir style, and throwing in Tarpé Mills trademarks like catfights and shower scenes, risqué but never graphic. And I'm thoroughly enjoying myself!

Marla, Bruno, Baroness, Whiffy, Gary, Dan.

Who would you cast in a "Miss Fury" film?

That's hard, because everyone I think of is dead. Bruno is Yul Brynner, of course, and the Baroness is Dietrich. I think Marla could be Jean Peters or Jane Greer ... one of those beautiful brunettes of mid-1940s noir. Whiffy is Sydney Greenstreet! Maybe Robert Walker for Gary Hale and Sterling Hayden for Dan Carey. Is there anyone like these people today?

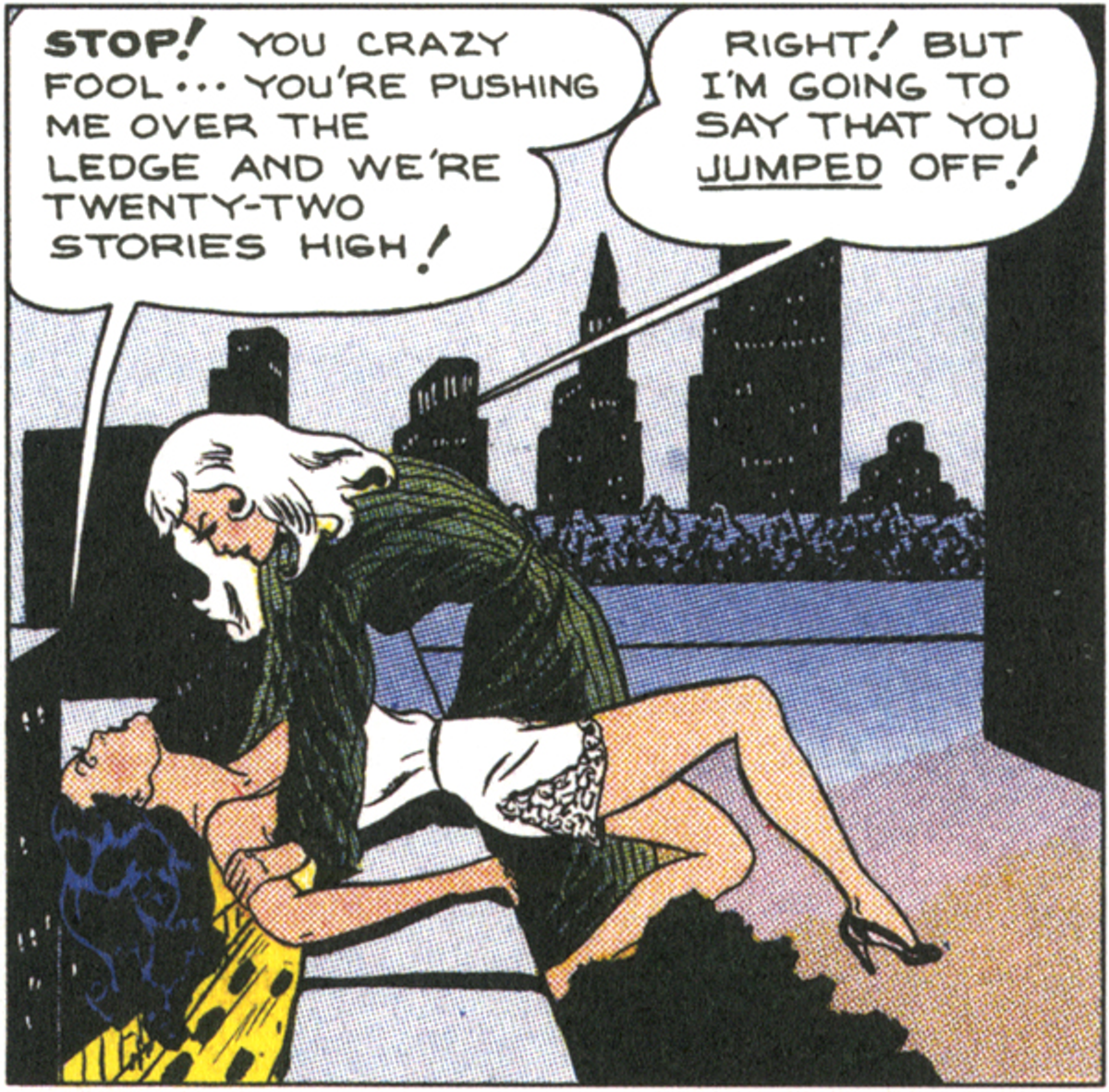

Marla "Miss Fury" Drake's first meeting with the Baroness isn't going very well. Art by Tarpé Mills.

OK, who'd win in a fight: Miss Fury or Catwoman?

It depends on which Catwoman. Should be quite a catfight.

Now let's say you're curating a historical exhibition featuring female comics artists. They'd represent different decades and genres, and be chosen for their significant graphic innovations as well as their influences on subsequent generations. Who would you include?

The 1900s, Grace Drayton. The 'teens, Nell Brinkley. The 1920s Flapper period, Brinkley and Ethel Hays. The 1930s, Fanny Y. Cory, who produced "Little Miss Muffet." 1940s would be Tarpé Mills and Dale Messick. The 1950s, maybe Hilda Terry, with her teen strip "Teena," representing the popular teen comics. The 1960s would have to be Marie Severin, the only one of two women then drawing superheroes.

After that, I show up and it becomes recent history.

And which female cartoonists are currently breaking new ground in visual narrative?

So many women drawing great graphic novels these days! Joyce Farmer's "Special Exits," Alison Bechdel's "Fun Home." Of course, Marjane Satrapi. Carol Tyler. Dame Darcy ... I love her! Miriam Libicki ... There are more women than ever before producing comics today, and those are only some that I can come up with off the top of my head.

Who'll be the subject of your next book?

I'm speaking with IDW, my publisher, about a collection of the Fiction House comics of Lily Renée. After I have put together a Renée collection, I will have done all the histories of women cartoonists that I want to do.

From "Dog Fight," Wet Satin #2, 1978. Art and story by Trina Robbins.

Copyright F+W Media Inc. 2011.

Salon is proud to feature content from Imprint, the fastest-growing design community on the web. Brought to you by Print magazine, America's oldest and most trusted design voice, Imprint features some of the biggest names in the industry covering visual culture from every angle. Imprint advances and expands the design conversation, providing fresh daily content to the community (and now to salon.com!), sparking conversation, competition, criticism, and passion among its members.

Shares