A trillion here, 2 trillion there, pretty soon, we're talking about real money! Or so you might think. While we still have no clear picture of what kind of deal Congress and the White House will finally cut to steer clear of debt ceiling disaster, we do know that some large numbers are being thrown around by both sides.

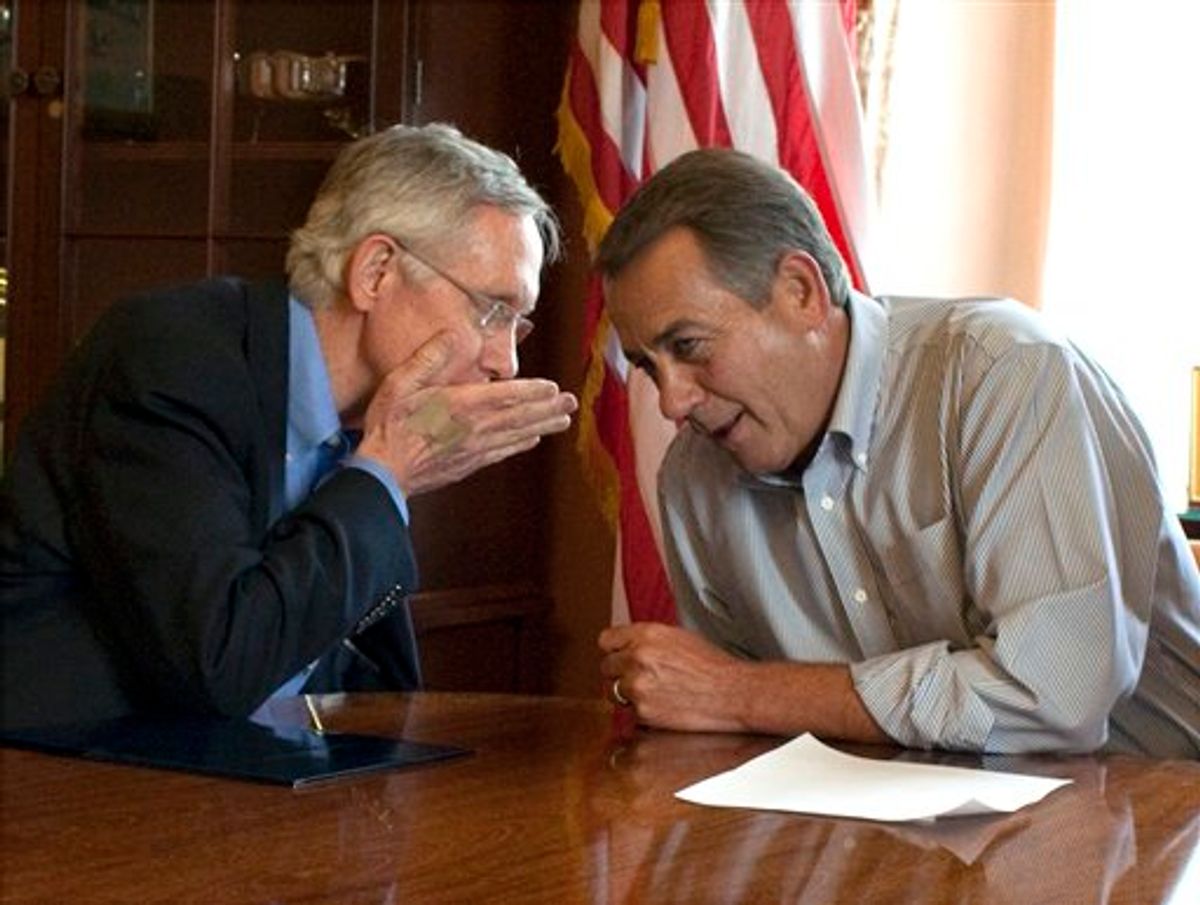

The first stage of the Boehner "Two Step Plan to Be Mean to Obama" promises "immediate" cuts of $1.2 trillion. Harry Reid's counter-proposal proposes $2.7 trillion in reductions, a total big enough to make most Democrats gulp at the prospect of the poor, sick and elderly suddenly shoved onto the street.

As previously noted here, however, more than half of that $2.7 trillion comes from winding down spending on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan as well as savings from interest payments on debt that the government won't have to pay since it will be borrowing less money. Which makes the Reid plan a little less scary. But what about the other half? We may not know the final shape of a debt ceiling deal, but it's safe to say that whatever happens, the ultimate agreement will include at least $1.2 trillion in the "discretionary spending cuts" that were agreed to by both sides during the negotiations led by Vice President Biden. And if you look at the legislative language for both the Reid and Boehner bills, they include very similar language on discretionary spending limits.

But here is where it gets tricky. Because the cuts are not exactly what most people would think of as "cuts." Discretionary spending authority -- the amount government is allowed to spend each year -- actually rises over the next 10 years. Under the Boehner plan, the 2021 cap is $1.234 trillion, or about $190 billion more than authorized for 2012. Under the Reid plan discretionary spending is capped at $1.228 trillion in 2021.

So you might well ask, if the amount that Congress is allowed to spend goes up each year, how can either side claim savings of a trillion dollars or more?

The answer: It's all about the baseline.

Budget planners assume a baseline in which spending rises at the same rate as inflation. Under the Biden framework, spending increases are capped at a rate less than inflation. The exact percentage isn't spelled out in the legislation, but one report pegged the spending cap at two-thirds the normal inflation rate.

"Savings" are calculated by subtracting what the government will spend with the cap in place from what the government would have spent if spending rose at the full inflation rate. Voilà! Spending, overall, continues to rise, even as a trillion or more dollars are "saved."

As I contemplated these numbers, I began to understand, for the first time, the psychology of a House Republican freshman. The closer you look at the U.S. federal budget process, the more it all seems like chicanery. But just to make sure, I called up the Center on Budget Policy and Priorities to see if I could get a little more clarity.

Jim Horney, CBPP's vice president for federal fiscal policy, argued that it is still "appropriate" to call the cap on spending authority a "cut," for the simple reason that if you hold spending increases to under the inflation rate, the amount of goods and services that can be purchased with that spending is going to fall, since costs will be rising at the full rate of inflation.

Here are some examples of programs that fall under the category of "discretionary spending":

The single largest non-defense discretionary program is the Veteran's Health Administration, which delivers free and low-cost health care to more than 8 million veterans. The National Institutes of Health is also entirely supported by discretionary funding. So are the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Drug Enforcement Agency, and the whole federal prison system. Federal aid to local school districts comes from the discretionary pot, as does the budget for the Food and Drug Administration. The National Park System operates because of discretionary funding, which puts it in the same company as the United States Coast Guard, the Transportation Safety Administration, and the Farm Service Agency.

I know some of my readers would be delighted to see the FBI, DEA and maybe even the whole federal prison system abolished. But if spending authority rises at two-thirds the rate of inflation for the next 10 years, school districts will be able to afford less heating, national parks will be forced to reduce hours and services, the NIH will be able to fund less research and veterans will get less healthcare -- depending on how congressional appropriators allocate funding under the caps.

So the cuts are real -- for the recipients.

But they're also a numbers game. There's a huge difference between a balanced budget or serious long-term deficit reduction and tweaks to discretionary spending caps based on inflation adjustments. And the more one learns how Congress plays this game, the more one understands why House Republicans are unwilling to endorse any compromise. And that leads us to an ugly conclusion: The better they grasp the numbers, the more determined they might be to drive us toward default.

Shares