I used to think genre fiction was for the slow-minded. Page turners, potboilers, pulp -- none of that interested me. That was for folks who liked their novels rubber-banded and soft-backed, who finished two books a year and read everything aloud.

There is a war against popularity in many MFA programs in America, and in my 20s, I was on the front lines. I wrote literary fiction, the only work serious and relevant enough to be worth my time. I cut my blue jeans off at the knees and called everything ironic. I read John Banville's "The Sea" by an actual sea. I wrote the kinds of hard-bitten, muscular novelettes young men are supposed to become famous for writing.

For a short time I morphed into John Ashbery; at 25, I was sort of a Michael Chabon lite. All the while I was tunneling outward across the sediment of recent American letters, digging hard for something worthwhile to say in my own stale fiction. Being original -- or even, God forbid, honest -- didn't interest me in the least. Instead I tried on disguises, trying to cobble my fiction together out of different styles and contexts. Words like "urgency" and "vitality" were my catchphrases.

I flailed, hilariously, to be sure my writing could not be confused with mere entertainment. I went through an experimental phase; I grew the requisite chin beard. I wrote text upside down, scribbled counterpoint in the margins. Every story I wrote contained footnotes. I was like John Gardner's Grendel: forever posturing, transforming the world with words but changing nothing.

In the evolution of the writer there is first Disillusionment, then Despair and finally Discovery -- believing in yourself and accepting what kind of writer you really want to be. For some, discovery probably occurs on backpacking treks across Europe, or maybe at sedate writers' retreats in the mountains of Vermont. For me it began in the paperback section of a Rite-Aid drugstore in Whitley City, Ky.

There was a book on the shelves by a man named Michael Connelly. I'd heard of Connelly before; his covers blared out at me on my trips to the bookstore, but I always stormed past him on my way to the "real" fiction. The book was called "The Closers." I bought it more out of curiosity than anything, prepared to laugh at how bad and base the prose was. Instead, I devoured the book in a few sittings, marveling at how Connelly worked the machine of his plot, how everything pitched forward and ran along the tracks of his story in this thrumming, gnashing rhythm. I immediately thought, "This isn't trash at all. This is something like art." Not long afterward I picked up another thriller, Peter Abrahams' masterpiece "Oblivion," and a kind of love affair with the genre was born.

Here, then, is how the young writer evolves -- I mean truly evolves, sloughs the old skin and gets to a point in his craft where he understands what it is he wants to elicit in the reader. I saw in "Oblivion" a chance to fuse what I had once loved (the aggressive, sardonic style of modern literary writers) onto this new thing (books that are written for the purpose of pure pleasure). In 2007 I began a short story called "Polly." My son, then 2 years old, sat on the couch beside me while I wrote. I had no idea what I was doing, but I did know one thing: this was no disguise. What I was writing came from something that felt immediate, fresh, right.

The thriller novelist's place in the culture is hazy. There are those whose novels ascend to literature (Connelly, Jeffrey Deaver, Karin Slaughter, Dennis Lehane, Laura Lippman), others who write only out of an urge to entertain the masses -- and then a world inside the cross stream. In those first thrillers I read, I actually found a common bond to the experimental writers I'd once mimicked; in some of these books -- Abrahams' "Oblivion" is certainly one -- the writer looks to unmoor the very literary style he has invoked. Abrahams' novel is a detective novel, but it is one that slowly becomes unhinged; it is Raymond Chandler held up to a fogged, cracked glass.

Yet thrillers, like all genre fiction, remain for the most part "beneath." There is a feeling in literature, more than any other art form, that books meant to simply entertain must be flawed. There is an entire cache of what critics call "beach reads," books that are disposable, forgettable, anti-literary. And this is where I have changed the most as a reader and also as a writer. As I began to dig in to a lot of thrillers, I came to believe that entertainment and reading for pleasure can be transcendent; that while art might be a hammer it is also a mirror, changeable and subjective. And there is a point where the boundary of the thriller genre rubs hard against a much more vast literary tradition. A lot of great writers exist on this axis.

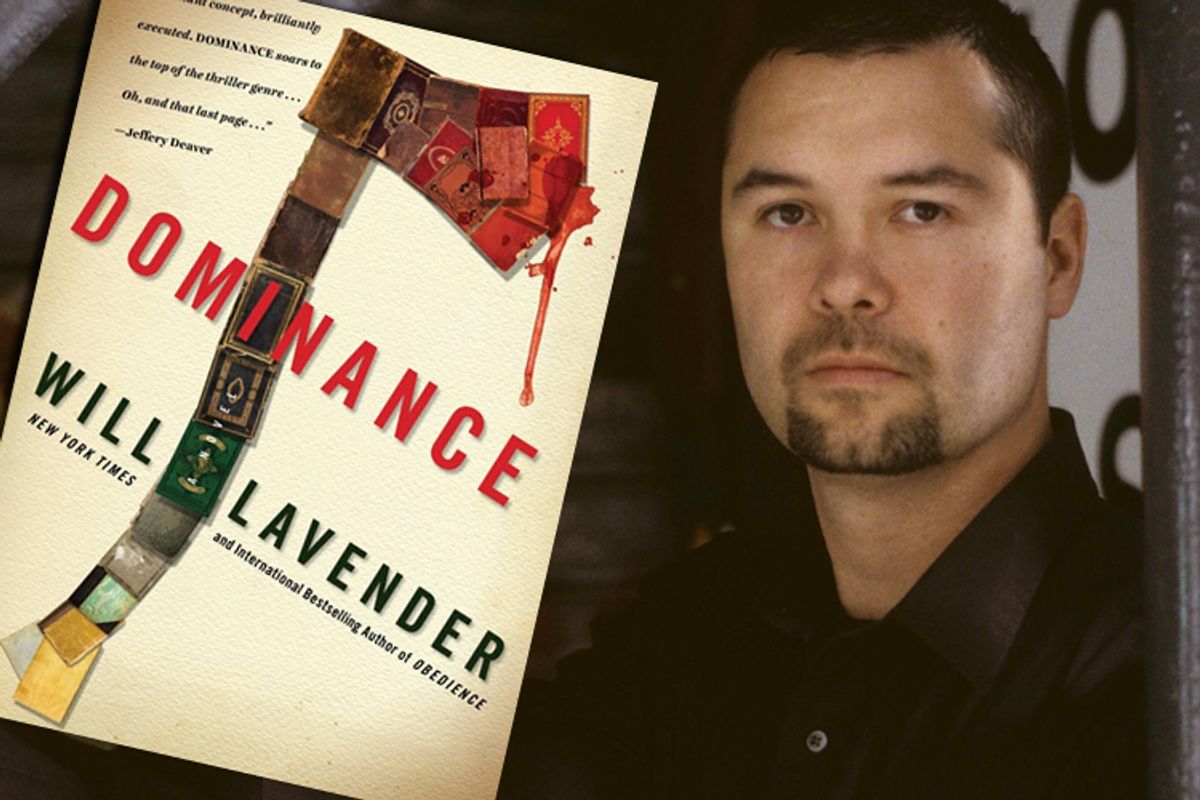

"Polly" became "Obedience," my first novel. A second book, "Dominance," was published earlier this month. Nevertheless, I'm still asked by a lot of people if I am ever going to change, if I have any aspirations to write a different (read: better) kind of fiction. Unspoken in the question, I think, is whether I am going to go back to the kind of writer I was in my 20s. I smile and nod and tell them that I am content. And it is true, because I have found something that suits me and makes me happy -- and this, I think, I hope, is how the writer knows that he has finally grown up.

Shares