About two months ago, we lost a great man. His name was Jay Criche, and he was a teacher.

He taught English for 30 years, 23 of them at Lake Forest High School. For most of that time, he was the head of the department, and he looked the part. He wore tweed sport coats most of the year, in weather cold or warm, and if I remember correctly, there were suede elbow patches on these sport coats. He wore small wire-framed glasses, a thick mustache, and his hair was dark, dusted with gray. He had a scholarly air because that's what he was, a scholar. His lessons, delivered from a seemingly ancient wooden podium, were Socratic in nature, the students peppered with questions, his expectations high, his mind open and wanting to be surprised.

I took his course when I was a junior, and the first book we read was "A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man." In those first few weeks, he showed us a caricature of James Joyce from the New York Review of Books. In it, Joyce's hands were rendered large, cupped and moving, as if paddling through water. Mr. Criche asked if anyone knew why the artist had depicted Joyce that way, and I raised my hand. "Is he swimming through a stream of consciousness?"

Mr. Criche cocked his head a bit, confirmed the answer, and a wave of validation swept over me. I hadn't known, until that moment, how badly I'd wanted his approval. I was going through some rough times at school and at home -- my face and back were covered in acne, my chest was concave, my last name sounded like food -- but in that class, I felt I had worth. After that, I took it upon myself to impress him. Though William Faulkner wasn't assigned reading, for weeks I brought "As I Lay Dying" to class, stacked neatly upon my other books, hoping he'd notice. (He didn't.)

He was kind to me, but I had no sense that he took particular notice of me. There were other, smarter kids in the class, and soon I fell back into my usual position -- of thinking I was just a little over average in most things. But near the end of the semester, we read "Macbeth." Believe me, this is not an easy play to connect to the lives of suburban high schoolers, but somehow he made the play seem electric, dangerous, relevant. After procrastinating till the night before it was due, I wrote a paper about the play -- the first paper I typed on a typewriter -- and turned it in the next day.

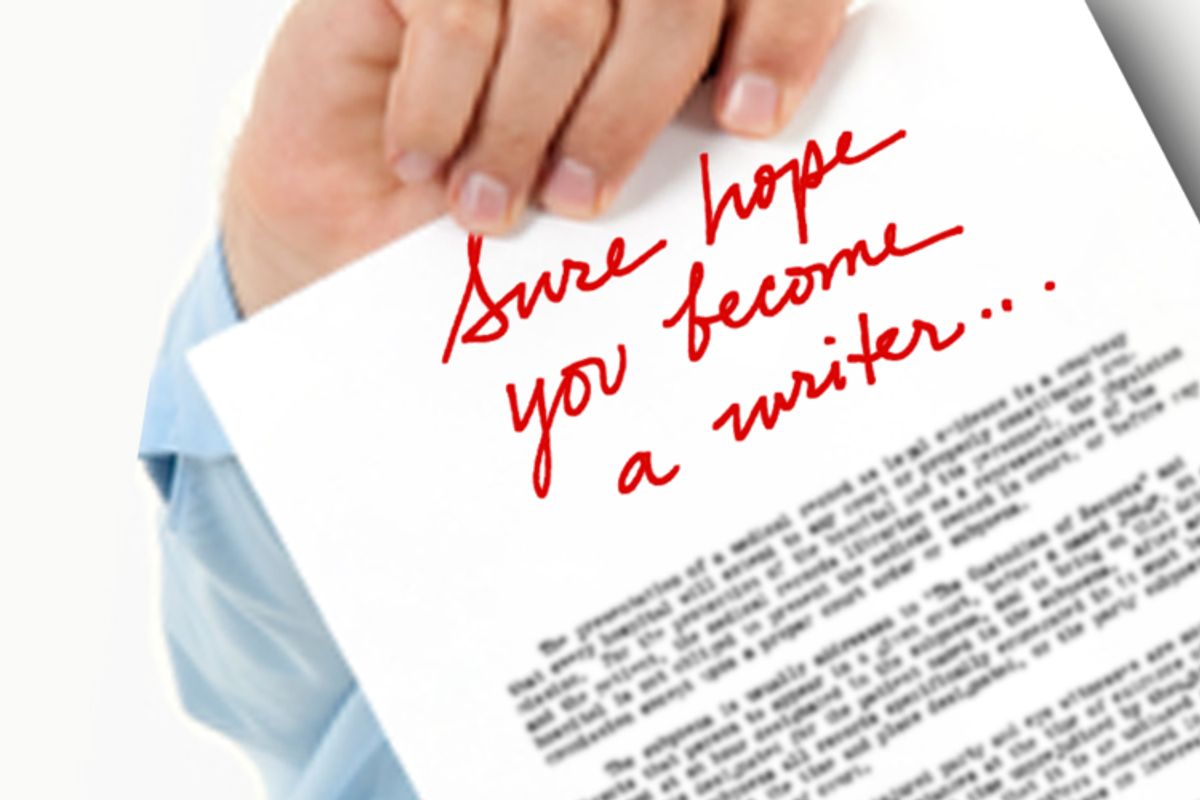

I got a good grade on it, and below the grade Mr. Criche wrote, "Sure hope you become a writer." That was it. Just those six words, written in his signature handwriting -- a bit shaky, but with a very steady baseline. It was the first time he or anyone had indicated in any way that writing was a career option for me. We'd never had any writers in our family line, and we didn't know any writers personally, even distantly, so writing for a living didn't seem something available to me. But then, just like that, it was as if he'd ripped off the ceiling and shown me the sky.

Over the next 10 years, I thought often about Mr. Criche's six words. Whenever I felt discouraged, and this was often, it was those six words that came back to me and gave me strength. When a few instructors in college gently and not-so-gently tried to tell me I had no talent, I held Mr. Criche's words before me like a shield. I didn't care what anyone else thought. Mr. Criche, head of the whole damned English department at Lake Forest High, said I could be a writer. So I put my head down and trudged forward.

Mr. Criche was part of a powerhouse English department at Lake Forest High School, a school that, I believe, knew then and knows now how to treat its teachers. Nationwide, almost half of our teachers quit before their fifth year, driven away by poor conditions and low pay, but in Lake Forest, the teachers were and are able to make careers and lives out of the profession. Most of my other English teachers from 1984 to 1988 -- Mr. Ferry, Mr. Hawkins, Ms. Pese, Mrs. Silber, Mrs. Lowey -- taught there for decades, most of them in the same classrooms, all of them master educators. Imagine the benefit the students there received, from getting pretty much a college-level education in high school from educators who have honed their craft for decades. Every kid in this country deserves the same thing.

I don't want to make this remembrance about the state of teachers in America, but Mr. Criche's passing came just when teachers are at their most vulnerable, at a time when they're fighting to assert and retain the dignity and artistry of their work. I don't remember Mr. Criche teaching us how to take standardized tests, but when we took them, we did well. I don't remember Mr. Criche gearing his lesson plans toward any state-regulated curricula, but we did pretty well on any and every scale. Why? Because he made us curious. He was curious, so we were curious. He was hungry for learning, so we were hungry, too. He made us want to impress him with the contents of our brains. He taught us how to think and why.

I miss him, but he won't be forgotten, not by me or the scores of students who sat before him. Teachers live on in a thousand hearts and minds, right? They're stuck with us. We follow them everywhere and always.

Shares