Although it's long accommodated a few idealists and loads of fans, the music industry is not for the faint of heart. On the contrary, it's always been long on tough guys and worse, for reasons that are not hard to figure out. Cash businesses conducted at night in places where alcohol is served would have their shady side even in nations where the liquor trade wasn't illegal for 14 crucial years, and although jukeboxes didn't catch on until well after Prohibition, the Mob was positioned to take them over, and get its mitts on record distribution into the bargain. Nor is it all about the Benjamins. If by popular music you mean domestic palliatives from "Home Sweet Home" to Celine Dion, OK, that's another realm. But most of what's now played in concert halls and honored at the Kennedy Center has its roots in antisocial impulses -- in a carpe diem hedonism that is a way of life for violent men with money to burn who know damn well they're destined for prison or the morgue.

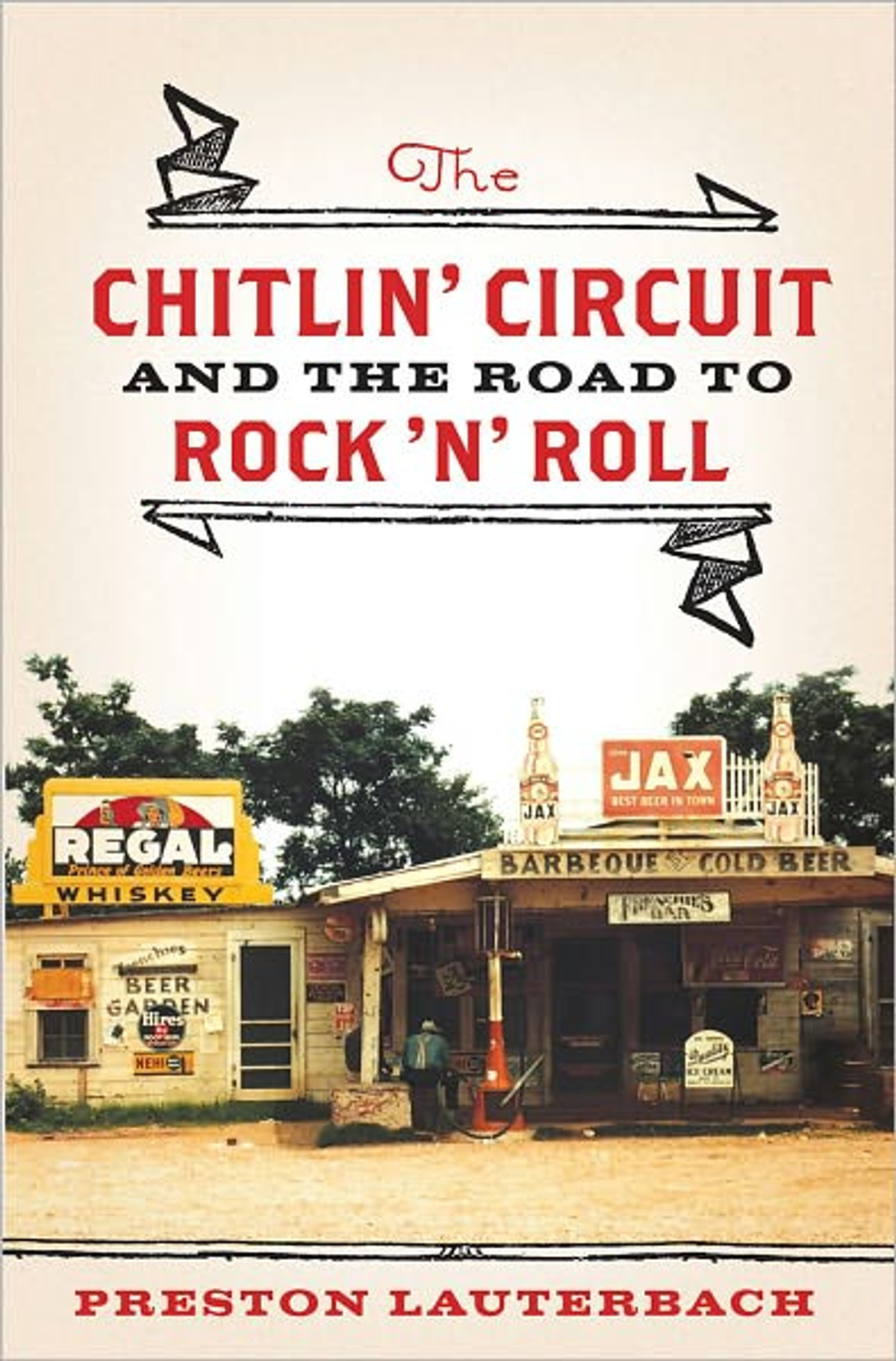

Most music books assume or briefly acknowledge these inconvenient facts when they don't ignore them altogether. But they're central to two recent histories and two recent memoirs, all four highly recommended. Memphis-based Preston Lauterbach's "The Chitlin' Circuit and the Roots of Rock 'n' Roll" relishes the criminal origins of the mostly southern black club scene from the early '30s to the late '60s. Journalist-bizzer Dan Charnas's history of the hip-hop industry, "The Big Payback," steers clear of much small-time thuggery and leaves brutal L.A. label boss Suge Knight to Ronin Ro's "Have Gun, Will Travel," but plenty of crime stories rise up as profits snowball. Ice-T's "Ice" devotes 25 steely pages to the lucrative heisting operation the rapper-actor ran before he made music his job. And '60s hitmaker Tommy James's "Me, the Mob, and the Music" is an artist memoir distinguished by its substantial portrait of American pop's most legendary gangster, Morris Levy.

Most music books assume or briefly acknowledge these inconvenient facts when they don't ignore them altogether. But they're central to two recent histories and two recent memoirs, all four highly recommended. Memphis-based Preston Lauterbach's "The Chitlin' Circuit and the Roots of Rock 'n' Roll" relishes the criminal origins of the mostly southern black club scene from the early '30s to the late '60s. Journalist-bizzer Dan Charnas's history of the hip-hop industry, "The Big Payback," steers clear of much small-time thuggery and leaves brutal L.A. label boss Suge Knight to Ronin Ro's "Have Gun, Will Travel," but plenty of crime stories rise up as profits snowball. Ice-T's "Ice" devotes 25 steely pages to the lucrative heisting operation the rapper-actor ran before he made music his job. And '60s hitmaker Tommy James's "Me, the Mob, and the Music" is an artist memoir distinguished by its substantial portrait of American pop's most legendary gangster, Morris Levy.

Owner of Roulette and countless other labels as well as the jazz club Birdland and the Strawberries record retailing chain, Levy is said to be the model for Hesh Rabkin of "The Sopranos" and deserves fuller treatment than the fast-moving 225-pager James wrote with Martin Fitzpatrick. After he died of cancer while appealing an extortion conviction in 1990, a few of Levy's machinations were detailed in the likes of Dorothy Wade and Justine Picardie's Ahmet Ertegun biography, "Music Man," and John A. Jackson's Alan Freed biography, "Big Beat Heat." But James's stories are the most closely observed to date. IRS men examine Levy's books for so long that he gives them their own office at Roulette, where low-level enforcers and future Genovese boss Tommy Eboli stroll in and out. Levy roughs up James's first manager and threatens James himself. When James gets his draft notice, Levy phones a friend who's on the board of both Chemical Bank and the Selective Service, and James is classified 4-F. Finally, in 1972, with the hits dried up anyway, James confronts Levy in a pill-fueled rage and walks out with his knees intact.

James hated Morris Levy. Yet he also loved him, and he's not the only one. With James, maybe this is understandable. Although he and his Shondells were no Paul Revere and the Raiders quality-wise, he was a smart, ambitious, hardworking kid compelled to learn the music business at 19, and so Levy inevitably became a father figure -- a father figure who robbed him of millions in royalties while overseeing a five-year run where James made his own pile touring, served as a youth advisor to Hubert Humphrey, and married a Mob-linked Roulette secretary whose dad forwarded the kids pharmaceutical samples from his Post Office job. But Levy had more sophisticated fans, especially in jazz, which he greatly preferred to rock and roll. Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie, and Nesuhi Ertegun are among the many to testify to his kindness and generosity. James simply says, "He was more fun to be with than anybody."

Levy -- who also shows up in "The Big Payback" when he acquires the groundbreaking hip-hop label Sugarhill in a usury scheme -- is the only white crook with a prominent role in these books. This is demographically unrepresentative. The Mob had its hooks into MCA, long America's dominant booking agency, and Levy's notorious predecessor Joe Glaser, who managed and fleeced both Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday, was only the best-known of the many Mob-linked operators who controlled the nightclubs that became such a big deal as of the '20s. For the most part, however, these were northern clubs, because the North was where jazz fans had money and where white gangsters were organized. Preston Lauterbach tells the story of their black counterparts in the South, where ruder music was germinating.

Lauterbach's kingpin is Denver Ferguson, second in Indianapolis's Bronzetown only to that seminal black capitalist, hair-straightening queen Madame C. J. Walker. Ferguson was a numbers tycoon from a frugal landowning family in a predominantly white Kentucky town. His printing business generated a specialty in gambling devices called "baseball tickets," and by the early '30s that operation, plus the real estate it bought, led to his brother Sea Ferguson's Cotton Club and his own Trianon Ballroom, and these ventures to the Ferguson Brothers Agency a decade later. Lauterbach cares plenty about music, offering insightful descriptions of, among others, Little Richard, Louis Jordan, Johnny Ace, Gatemouth Brown, and journalist-bandleader Walter Barnes, whose well-embellished "Chicago Defender" columns on the South's many bronzetown "strolls" did much to raise African-American cultural consciousness in the '30s. But what he emphasizes about Ferguson is his workaholic organizational capacities. Though Ferguson accrued capital breaking the law, he was basically a businessman, and a responsible one: "He collected black dollars in underworld trade and gave back to the community at large, carving economic independence out for himself and employing black locals."

At times Lauterbach finds his material so colorful he can't resist providing prose to match, and he obsesses predictably on the ineffable southernness of rock and roll. But these are forgivable tics given what he's achieved -- a coherent, musically savvy history of a performance culture that until now was known only piecemeal. In addition to Denver Ferguson we get the lowdown on Houston's Don Robey, remembered because he owned a record label, and Memphis's Sunbeam Mitchell and Bob Henry, uncelebrated because they didn't. We also get revealing glimpses of unsafe havens where black men who knew damn well the white man was keeping them down could have more fun than anywhere -- where music imparted spiritual concord to wine, women, and craps.

A redolent factoid is the name of the fraternal organization that staged the Baby Doll Dance at Natchez, Mississippi's Rhythm Club on April 23, 1940: the Moneywasters Social Club. How better declare your dissent from the Puritan ethic than by calling yourselves the Moneywasters? Unfortunately, the reason these spendthrifts are remembered is the 209 people who died that night in a one-exit venue where Spanish moss had been doused with kerosene to disperse mosquitoes -- including Walter Barnes, who had seen lots of fires and kept playing in a doomed attempt at crowd management. Also unfortunately, what has been dubbed the Natchez Dance Hall Holocaust would have been less deadly had not the Moneywasters boarded the windows and padlocked the back door to thwart freeloaders. But that's the kind of tradeoff you live and sometimes die with when you aim to have more fun than anybody.

Although most of the chitlin'-circuit impresarios went to their rest in more comfort than they'd been born to -- and more comfort than their artists, especially the earlier ones -- none of them got rich; Don Robey ended up selling Duke-Peacock for $100,000 and a leased Cadillac. Two generations later, their successors have profited rather more spectacularly, marketing a rock and roll offshoot that began as un-southern as any African-American music this side of Anthony Braxton. The even tone of Dan Charnas's account of this big payback differs markedly from Lauterbach's. A Boston University summa whose thesis was entitled "Musical Apartheid in America" and who always capitalizes "Black" and "White," Charnas was an early contributor to "The Source" and worked in the record business for much of the '90s. "The Big Payback" fuses these complementary orientations in a swift, detailed, thoughtful narrative that stands tall alongside Jeff Chang's canonical hip-hop overview "Can't Stop Won't Stop." At 638 pages, it weaves substantial portraits of at least 50 artists, businessmen, and radio pros into a story that isn't quite encyclopedic -- it fast-forwards from 2000 and pretty much skips the Dirty South -- but justifies its grand conclusion: ""Hip-hop succeeded not by being correct. It succeeded by being." In its materialistic ubiquity, hip-hop won. It is takeover. America has officially been remixed."

Half a century after Denver Ferguson opened the Trianon Ballroom, Afro-America had been changed drastically by an entrenched civil rights movement, an expanding economy that stalled just as the black middle class was taking off, and the partial breaching of racial barriers by rock and roll itself. Maybe the runners and enforcers who manned the chitlin' circuit weren't all that different from the many casual drug dealers who find a better way in Charnas's book: among them, in roughly ascending order of seriousness, Russell Simmons, Jay-Z, Damon Dash, Biggie Smalls, and Chris Lighty (plus the very casual young Ice-T of "Ice," well before he figured out that robbing jewelry stores with a sledgehammer was a better deal). But the general mood was certainly angrier and more polarized -- fatherless children were everywhere, and so were guns. Although hip-hop refutes the Lauterbach-approved Jane Jacobs truism that public housing projects destroy ""innovative economies"" (her italics), none of the thuggery described by Lauterbach, James, or any other pop historian approaches the murders of Tupac and Biggie. And those are merely the most spectacular examples of what Charnas calls "hip-hop's cycle of violent one-upmanship," which made the beatdown a social currency.

In "Ice," Ice-T observes that this cycle began with escalating hostilities among L.A.'s gangbangers. But these were obviously cranked up by the profits at stake in the inner city's innovative response to Reaganism's entrepreneurial imperative: the drug trade -- especially, as Ice-T also observes, "once crack hit." Of the small-time dealers named above, several of whom sold only weed, Simmons and Dash were born businessmen on their way to safer hustles. Ice-T was an army veteran and a non-deadbeat dad who preferred to keep his ambitions reasonable -- once he went into the crime business, he refused to use a gun on the job or traffic drugs. Biggie and Jay-Z, on the other hand, had much bigger dreams than street dealing could satisfy, and turned to music to fulfill them, as did two less casual dealers, 50 Cent and Wu-Tang headman RZA. Who knows whether any of these men had what it takes to become a crime boss -- probably not, we hope. But they kept their eyes on the prize, which was untold wealth. And except for the slain Biggie, all made bigger bucks rapping than any but a few of the African-American musicians who preceded them. That is, all made out like gangsters, including the moderately talented 50, who cashed out of his VitaminWater deal with as much as $100 million and has a net worth Charnas estimates at nearly half a billion.

One of Charnas's most fascinating portraits is of supermanager Chris Lighty. His absentee dad an FBI agent, Lighty may be the one guy here with the makings of a crime boss -- like Morris Levy, he's proven "calm, but completely capable of carnage." After one particularly fraught beatdown early in a career that began with his Violators crew providing muscle for DJ Red Alert, Russell Simmons's Israeli-born partner, Lyor Cohen, told Lighty: "You have to make up your mind. Do you want to be "that "guy, or "this "guy?" Lighty chose "this "guy, but when necessary -- convincing Suge Knight to OK a Def Jam video, say -- he became "that" guy. Charnas says Lighty got into hip-hop because he "was interested in girls and thrills." He took 15 percent of 50 Cent's VitaminWater money and may well be worth as much as his client.

"The Big Payback" documents the phenomenal talent, faith, and enterprise that went into hip-hop's takeover. Little Richard and Louis Jordan were musical titans, but Jay-Z and Wu-Tang belong in their company, and even adjusting for history, Chris Lighty and Puffy Combs as well as Jay-Z the label exec dwarf Denver Ferguson and Don Robey. And though there were quite a few whites and middle-class blacks in the hip-hop mix, many crucial innovators came up from circumstances as daunting as those of Ferguson's time. Charnas celebrates their admirable achievements without sensationalism or sentimentality.

Yet though he's not a political idealist on the order of fellow historian Jeff Chang, the onetime student of musical apartheid sees hip-hop's limitations. Economically, "there is still no great Black-owned major record company, no film studio. The winning paradigm...seems to be the joint venture." And culturally, the man who again and again depicts gangsters finding a better way -- the scariest of Lighty's Violators now has his master's and a guidance counselor job -- is less sanguine about gangsta rap, starring those hyperreal villains who became hip-hop's commercial mainstay by pretending to be ordinary thugs and sometimes acting like same. Charnas believes that what got Tupac killed was his pursuit of a "street credibility...measured by money, violence, brutality, and blind loyalty."

Such gangsta images as the gun and the beatdown have gradually lost ground to a carpe diem hedonism long on a sexist sexual candor that offends its female fans far less than feminists of either gender would prefer -- no more "correct" than gangsta, but less deadly in its generalized escapism. Hip-hop accommodates many other kinds of expression, and I'm gratified when it makes them work. But at hip-hop's core is a dissent from the Puritan ethic that achieves its own kind of spiritual concord. And behind it, as behind many popular musics before it, are more or less shady businessmen with a special appreciation for girls and thrills.

Shares