Young people throughout the Arab world are in a state of rebellion. In the past two years, the world has seen Muslim youth help overthrow authoritarian presidents in Egypt and Tunisia, and challenge the suspicious ballot results of an Iranian election. In a break from the region's often-violent past, the anger and frustration of this new generation of revolutionaries has been expressed in surprising ways. Some young Muslims are using humor, hip-hop and peaceful demonstrations to protest tyrannical leaders and Muslim extremists who brutalize their countrymen and demonize the Islamic faith.

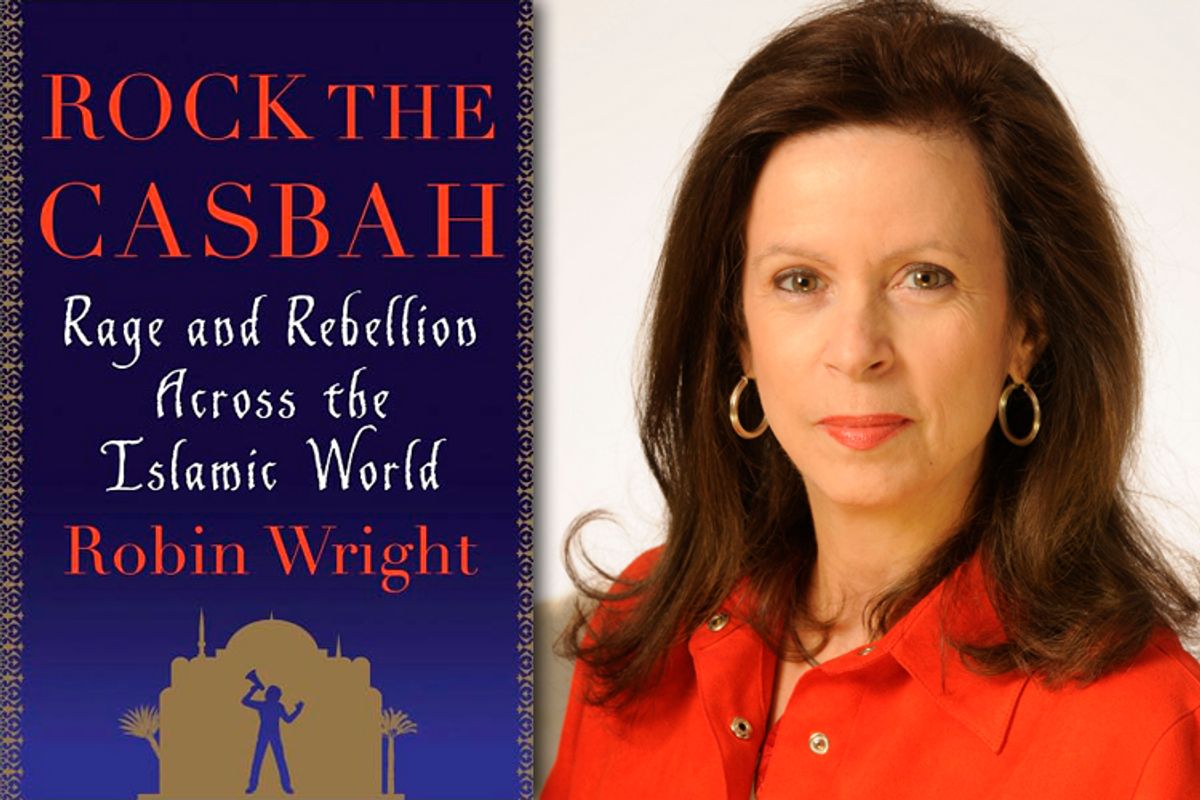

In "Rock the Casbah," veteran journalist Robin Wright highlights the artistic and political work of numerous counter-jihadis and explains why she believes the current rebellions in the Middle East are distinctly different from earlier ones. Using Internet tools like Facebook and Twitter, youth have been able to expand the reach of their nonviolent messages for widespread social, cultural and political change. They are mobilizing their peers online and in the streets in places as distinct as Syria, Palestine and Yemen.

Salon spoke to Wright about the historical precedents for the counter-jihad generation, the changing meaning of martyrdom and the power of the pink hijab.

In the 40 years you have been writing about the Middle East, what key changes have you seen?

The modern Islamic revival has had four phases. The first one began with the 1973 Middle East war, which is when Islam became an effective tool for mobilizing people. In the next phase was the rise of extremism in the 1980s. I was in Beirut when the first suicide bombs went off against American targets at two embassies and the U.S. Marine compound. Although the use of suicide bombs began with the Shiites, it had extended to the Sunnis by the end of the 1980s. The 1990s was the third phase, when Islamist movements began using the ballot as well as the bullet to integrate into politics. Hezbollah came out from underground for the first time, and its members ran for Parliament. This also happened with the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, Islah in Yemen, and the Islamic Action Front in Jordan. What all three of these phases have in common is that they were reactive, whether to autocratic leaders, the Arab-Israeli conflict, or foreign intervention. In the current phase, which grew out of the aftermath of 9/11, Muslims are working proactively to reject both the political status quo of autocracies, outdated monarchies and extremism.

What caused this change?

One of the biggest factors is demographics. Two-thirds of the 300 million people in the Arab world are under 30 years old. No regime has been able to accommodate the number of young people moving into the labor force. Muslims are increasingly turning against extremist groups like al-Qaida because they've been unable to provide basic needs, like housing, education, healthcare or employment. Also, for the first time the majority of youth are literate. They may not have graduated from high school, but they have the ability to read about what has happened elsewhere in the world. They also have access to an extraordinary number of sources of information. In 1996, Al Jazeera became the first satellite station that could circumvent the state-controlled media in every country. Today there are over 500 satellite channels in the Arab world, not to mention the Internet.

How is this "counter-jihad generation" distinct from their forebears?

Counter-jihadis are young people who are striking out on their own to create a new future. This is happening in many different forms, from protesting in the street to rapping. They are using their voices to convey a message that represents their generation. Comedians are challenging the status quo and rejecting extremists. Playwrights are using the word "jihad" in their titles in an attempt to reclaim the idea from the militants. In this part of the world, poetry is still a strong literary form, and poets are writing against radical fatwas. Counter-jihadis are expressing themselves in many ways, but they're all part of the same phenomenon: defining what they want to politicians and other traditional elites.

What is so striking about the uprisings in the Arab world is that all the protests started with the use of peaceful civil disobedience. Libya disintegrated into civil conflict, but in Syria they're still predominantly trying to use peaceful demonstrations. That is really an extraordinary change in the world's most volatile region.

Are the artists and protesters communicating with each other across national borders?

People told me common stories, but they didn't tend to know about each other. Several people told me that they were frightened after 9/11 because they were condemned by so many parts of the world just for being Muslim, even though they had nothing to do with bin Laden and felt he had besmirched their religion. They were looking for a way to do something that would rescue their faith.

The mission of Tissa Hami is to redefine the Muslim presence in the United States through comedy. She'd always been funny and loved cracking jokes. Tissa was an investment banker in Boston on 9/11, and after enrolling in a comedy class, dropped everything to become a comedian. Comedy has become a common language that spans the Islamic world. Telling jokes is a way people can belittle, question, challenge or tell the truth about politics and politicians.

How do they share their work with one another?

Mostly through the Internet, but they all have different ways. In the case of El General in Tunisia, he put his song on Facebook. He had no idea it would generate the kind of response it did. Now he's enormously popular, and his music has been played in other countries as one of the anthems of opposition. He has recorded a lot of music since then and a lot of it is political. Some of the most interesting rappers have tapped into the political environment, and for them, that is the most immediate, important and stimulating part about it. The Palestinian group, DAM, raps against drug use and a sewage project that is close to a children's school. They talk about all kinds of issues that are particular to their neighborhood as opposed to their country. It's not just against the autocrats and the extremists.

How widespread are technological tools like Facebook and Twitter?

Access varies from country to country. There are a lot of arguments about whether the number of people using these technologies is the majority, but it doesn't have to be the majority in order to generate a significant opposition. All it takes is a few people who use these tools and have that message spread through the legendary neighborhood grapevines.

How have these tools aided the counter-jihad?

The virtual uprising began in Iran in 2009 after the disputed presidential election because the press was banned. Young Iranians used cellphones to capture pictures on the street and sent them out to let the world know what was really happening there. One of the most moving videos was of a young woman named Neda Agha-Soltan, whose death after being shot by a sniper was captured on someone's cellphone. That video was one of the defining moments of the protest.

Over the next two years, Twitter and Facebook really took off, so that by the time Tunisia erupted in late December of last year, one in five Tunisians was on Facebook. Facebook was the one outlet the government couldn't censor or manipulate. So, in a country that banned rap, El General got his song out that challenged Ben Ali. He said things that politicians did not dare say against a president who had ruled for 23 years. The Egyptian uprising took off after Tunisia because of a Facebook page started called "We are all Khaled Said," who was a younger blogger that had been arrested and beaten to death by police in the streets of Cairo in the middle of last year. That led to tens of thousands going out into the streets on Jan. 25; 18 days later, the president of Egypt, who'd been in power for 30 years, was gone.

Martyrdom has significance in Islam, and each of the uprisings has had one. What function did these people's deaths serve?

Technology has allowed counter-jihadis to communicate an entirely different set of values, goals and tactics. After three decades of associating the word "martyr" with suicide bombers, you now have people being called martyrs who weren't trying to hurt anyone else and died in the process of protesting. In the case of Mohamed Bouazizi, the young Tunisian street vendor who died as a result of self-immolation, he was trying to shame a corrupt government. Neda was out peacefully protesting a disputed election. Hamza al-Khatib was a 13-year-old boy in Syria who tried to challenge the arrest of his friends who had been arrested for writing anti-government graffiti on public walls. The process has generated the phenomenon of a new kind of martyrdom that isn't about the destruction of other people's lives. It is about using the most precious essence of your own life to change the political system.

Are social networking sites virtual stand-ins for more traditional gathering places, like mosques?

They supplement the mosque. These are all leaderless movements, and that's quite remarkable. They could probably use a little bit more leadership, but the fact is that it's through this new means of communication that the youth have created bodies that have no head. They also don't have any ideology except that they want to oust the system. They have been rallied by a combination of technology and principles, not by a leader or an ideology. That may be their vulnerability down the road, but it's certainly been stunningly effective in some places already.

What roles are women playing in the recasting of Islamic societies?

The two engines of change in the region are youth, because of the demographics, and women, because for the first time the majority of them are literate in every country. Women want to have more control over their lives. That doesn't necessary mean they want to become a doctor or lawyer, but they do want to be able to marry when they're ready to, get an education, and have a sense that they're doing something useful with their lives.

The women were at the forefront of the uprisings in both Syria and Yemen. They've even had all-women uprisings, just to be clear that they're as much a part of this as the men. It is clear that women still have an enormous way to go. In Cairo's aftermath of Mubarak's ousting, they tried to have a million women's march in Tahrir Square, but the men blocked them, harassed them, and gave them a hard time. Getting women's rights is a long way off, but in the United States we can't get an Equal Rights Amendment either.

Are there specific issues women are advocating for?

Women in the Middle East are going through something that women of my generation went through in the United States. During the women's liberation movement in the 1960s, women stopped waiting for men to pass laws that would empower them or change the dynamics of personal relationships. They began to push for rights in their own way, and that's what you're seeing now in many parts of the Arab world. Women have had enough with men saying they need better political systems before they deal with rights for women, and they're demanding their rights be pushed to the front. That's why the "pink hijabi" is so important.

What is the "pink hijab" generation?

Forty years ago almost no women wore hijab, and today over 80 percent wear it. Yet most women now wear hijabs that are very colorful and tied in creative ways. They aren't black; they're sometimes even adorned with things like sparkles and sequins, because the women want to be fashionable while also observing the modesty of their faith. Women want to wear the veil, and they want to make decisions for themselves. It's a really interesting combination of modernity and tradition.

What are the challenges the youth in these countries face as they move forward?

The next generation in the Arab world is going to be very tough.There will be many setbacks and diversions. It's now a generation after the demise of the Soviet Union, and still there is a former communist and KGB spy chief in power in Moscow. A generation after Nelson Mandela walked to freedom in South Africa, many blacks are economically worse off than they were under apartheid, and life expectancy has decreased. The majority rule government has not taken them seriously. Egypt and Tunisia have gone through the first of a multi-phase political, economic and social transformation, and there is so much work ahead. Change takes a long time in every place, and it will be very difficult in this most volatile region.

What role should America play in supporting Muslim youth resistance movements?

We need to reach out beyond the traditional elites who are our contacts and understand that we need a better grasp of what's happening on the ground. Instead of propping up the militaries, we need to use our aid to help generate jobs; the real challenge will often be economic. With the possible exception of Saudi Arabia, no country in the Middle East can afford democracy. We're spending something like $10 billion each month to fight a war in Afghanistan, but our Congress is reluctant to spend money to help countries with their rebuilding process.

There was a heartbreaking story I heard in Egypt about a camel driver who worked at the pyramids. He said he could no longer feed his family and he could no longer feed his camel, so he had to consider feeding his camel to his family in order to survive. But then he would have no job. The U.S. has to use its resources more wisely to ensure that the political process that has begun is not diverted or destroyed by economic issues. That said, we also need to allow these countries to learn through their own experience instead of rushing in to tell them what to do and how to do it. To be credible and legitimate, the change has to be defined and achieved by the people themselves.

Shares