"Our greatest primary task is to put people to work. This is no unsolvable problem if we face it wisely and courageously. It can be accomplished in part by direct recruiting by the Government itself, treating the task as we would treat the emergency of a war, but at the same time, through this employment, accomplishing great -- greatly needed projects to stimulate and reorganize the use of our great natural resources."

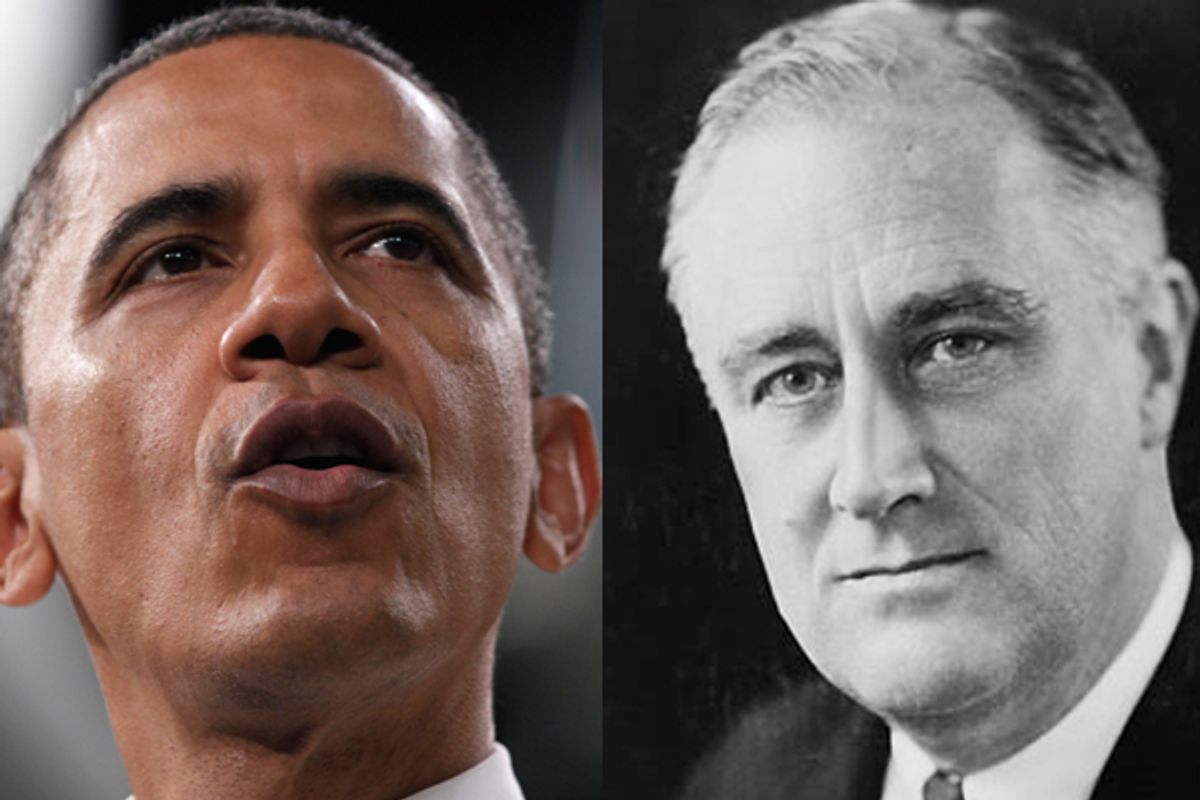

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, March 4, 1933

The economic news of the past few weeks -- highlighted by the debt ceiling debacle; the downgrade of US credit worthiness; the wild gyrations in the stock market and the wholly inadequate growth in the US job market in June and July -- all seem to point to one thing: the economic crisis that began in 2008 is far from over.

Worse still, given the political gridlock in Washington and the inability and/or unwillingness of the leadership on both sides of the political aisle to face the real crisis we face today -- the jobs crisis -- the prospects for a meaningful recovery seem remote at best. Many economists predict that the US will slide back into a recession. This is bad news for the millions upon millions of Americans who are out of work; bad news as well for the millions of young people just entering the work force. For the first time since the Great Depression, we face the ugly prospect of the loss of skills that often comes with long term unemployment or the lack of meaningful career opportunities for our youth.

One would think that in the face of such a calamity our government would do everything within its power to expand or at least maintain the workforce. But with the current Administration having embraced the mantra of deficit reduction and budget slashing, and with one branch of Congress ideologically opposed to government intervention in the economy, government layoffs, especially at the state and local level, are actually pushing up the rate of unemployment.

Over three quarters of a century ago, when faced with a similar jobs deficit, Franklin Roosevelt used the power of the federal government to do just the opposite -- to put people to work. Under the auspices of such New Deal programs as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) or the Works Progress Administration (WPA) millions of Americans found meaningful employment restoring our nation’s forests and watersheds and building the economic infrastructure we needed to grow the economy well into the future. Equally important, the skills required to build the 1000s of bridges, roads, schools, airports, dams and other key pieces of economic infrastructure necessary for a modern economy were not lost to that generation.

FDR did this because -- as he said in his first inaugural -- the most immediate and primary tasked needed to meet the economic emergency was to put people to work. This not only led to a significant drop in the unemployment rate (by more than 10 percent in his first term), it also helped fuel a period of economic expansion that would average 14 percent per year for the next four years.

Thanks to these efforts, the American people could look to the future with confidence rather than fear. Yes, times were hard. But under the leadership of the Roosevelt Administration, the federal government was engaged in an active effort to provide real jobs -- not handouts -- to millions and the industrial expertise we needed to meet the challenges of the Second World War were in place at the critical hour.

The national unemployment rate has now been at roughly 9 percent for more than two years. By any measure such a statistic -- which tells us little about the millions of under employed or those who have given up looking for work -- constitutes a national crisis. Yet all we hear about these days in Washington is the need to cut government spending (including federal aid to states) and reduce the deficit. Following this false logic will lay off more workers in the midst of the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. Given the dire state of affairs, the American people are right to fear the future. In addition to a jobs deficit, we now face a deficit of leadership at a time when we can least afford it.

David Woolner is a Senior Fellow and Hyde Park Resident Historian for the Roosevelt Institute.

Shares