In 1974, while working at a garment company in San Francisco, a native New Yorker named William "Picasso" Gaglione walked up to Darlene Domel, a Chicagoan working at the same company, and said, "Close your eyes and put out your hand." With her eyes closed and her heart in her throat, Darlene offered him her open palm. She then felt a tiny weight in the center of it. He pressed her fingers around that little lump, and she then felt the brush of a kiss over her fisted hand. When next she opened her eyes, he turned and walked away. Upon opening her fingers, she saw a small packet in the palm of her hand. In it, she found a tiny little rubber stamp of a star.

In 1974, while working at a garment company in San Francisco, a native New Yorker named William "Picasso" Gaglione walked up to Darlene Domel, a Chicagoan working at the same company, and said, "Close your eyes and put out your hand." With her eyes closed and her heart in her throat, Darlene offered him her open palm. She then felt a tiny weight in the center of it. He pressed her fingers around that little lump, and she then felt the brush of a kiss over her fisted hand. When next she opened her eyes, he turned and walked away. Upon opening her fingers, she saw a small packet in the palm of her hand. In it, she found a tiny little rubber stamp of a star.

"It seems quite charming now that my life changed directions under the sign of a rubber star," Domel says, 37 years later. "I found his bushy moustache and the killer smile a devastating combination. His New York accent charmed me. He was not like anyone I had ever known. He did not fit my ideal fantasy. He wore traditional long sleeve shirts and pants when everyone else was in jeans and t-shirts. He wore only all black or all white. To tease him I bought him a red leather belt at a thrift shop. He began to wear it every day. I knew I was in deep trouble."

At Esprit de Corp, Picasso was in shipping and Darlene worked in sales. He had a sign posted on top of his desk that said, "Dada is everywhere." One day, Domel stopped and asked him what it meant. He began to explain that Dada was an art movement when she interrupted to say she knew that, and having seen the stickers all over the city, simply wondered what they meant. He was impressed to find out she knew about Dada and the Surrealists. They began to go on lunch breaks together and talked about art and art movements, all the while pretending their new friendship was anything but platonic flirtation.

Gaglione, it turned out, was widely known around the world as a consummate mail artist. As a young man, he was taken by the Fluxus and Dada movements; in fact, his nom de plume, before adopting Picasso as a nickname, was "Dadaland." "He never stopped surprising me in the ways he looked at the world," says Domel. "The kind of visual poetry he created and the materials he used. He made art in ways that I had never seen before, little photocopied booklets he called 'zines.' I loved it. He made montages from photo booth pictures. He collected pictures of the backs of heads. He created collages with elements of old etchings that reminded me of Max Ernst."

They fell madly in love. But somewhere along the line, their relationship ended. Gaglione married someone else. Domel was heartbroken and moved to Miami and tried to forget. There, she rode out the rest of the decade.

By 1981, Gaglione was divorced and searching for Domel. They reconnected in San Francisco, where Gaglione was working for a mutual friend who had started a rubber stamp company at his urging. It wasn't long before they bought their own vulcanizer machine and began to make their own rubber stamps as a way to showcase and reproduce his artwork. "If we buy this machine," he had said, "we can make our own stamps, and it will save us a lot of money." "Like a fool," she says, smiling, "I believed him."

They quickly realized there was an audience for rubber stamps. "We took all of Picasso's early designs to a flea market one day," says Domel, "and to our surprise, people bought them. After that, we went to flea markets every weekend to sell more stamps. Pretty soon, there were two or three guys helping him." "And we were in business for real," says Gaglione, finishing her sentence.

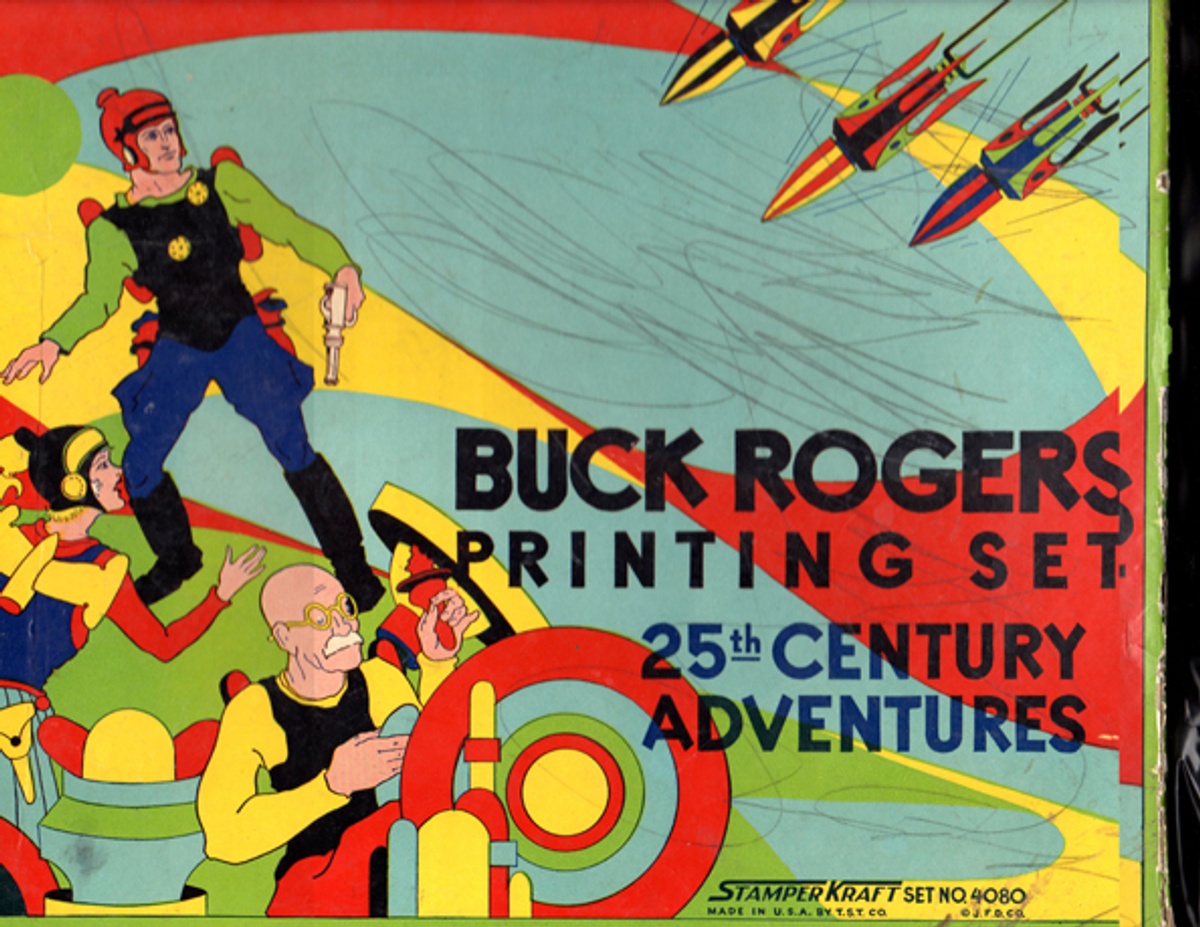

Unbeknownst to them at the time, rubber-stamping had been an American pastime for almost 100 years. After stumbling upon a '30s-era stamp set, they started to track down other stamp sets from bygone eras, some going back to the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago.

Initially, they set up shop in the basement of their San Francisco home. Early on Domel knew that in order to expand the business they would need to get it out of their house. Meanwhile, Gaglione set up a makeshift rubber stamp museum and production room. "Eventually I realized we had 14 people a day coming through our basement from 7 a.m. to 9 p.m. making stamps," she says. "A lot of our business was through mail order. There were magazines and conventions that started to pop up all over the country."

By the '90s, their business, then called Stamp Francisco, blossomed into a multimillion-dollar operation with over 100 employees. "The business moved out of the mail artist's world," says Domel, "and moved into a burgeoning hands-on crafting movement. We knew we had to build an industry." It wasn't long, however, before big companies, without the attention to detail they encouraged, came in and started to make "slave-labor-produced crap." This flooded the market, and the wholesale market for stamps collapsed by the end of the decade.

"We have survived by innovating," Domel continues, "by creating our own style of fine art hand-made rubber-stamping. We only deal with our end-users these days. We go out on the road and connect with our customers directly."

The couple ended up back in Chicago with their rubber-stamping operation housed, once more, in the basement of their home. This time around, they christened their company and museum Stampland. The couple tried the storefront approach, but after moving in and out of several locations in Chicago's Ukrainian Village neighborhood, this July 2010, Gaglione and Domel decided to move the whole operation to "a house in the country outside Gurnee, Illinois."

With a small but dedicated staff, they still plan on offering affordable stamp classes to the public, and will continue to custom-make thousands of rubber stamps for collectors and renegade handmade aficionados around the world. Along with fellow mail artist Scott Helmes, who lives in Minneapolis, Gaglione and Domel possess the world's largest collection of rubber stamps sets, which they'll proudly continue to showcase and discuss passionately in their creative workshops.

"When you grow up in a city like New York or Chicago," says Gaglione, "you're surrounded by art all the time. What we do at Stampland is a reflection of that, no matter where our museum resides."

Copyright F+W Media Inc. 2011.

Salon is proud to feature content from Imprint, the fastest-growing design community on the web. Brought to you by Print magazine, America's oldest and most trusted design voice, Imprint features some of the biggest names in the industry covering visual culture from every angle. Imprint advances and expands the design conversation, providing fresh daily content to the community (and now to salon.com!), sparking conversation, competition, criticism, and passion among its members.

Shares