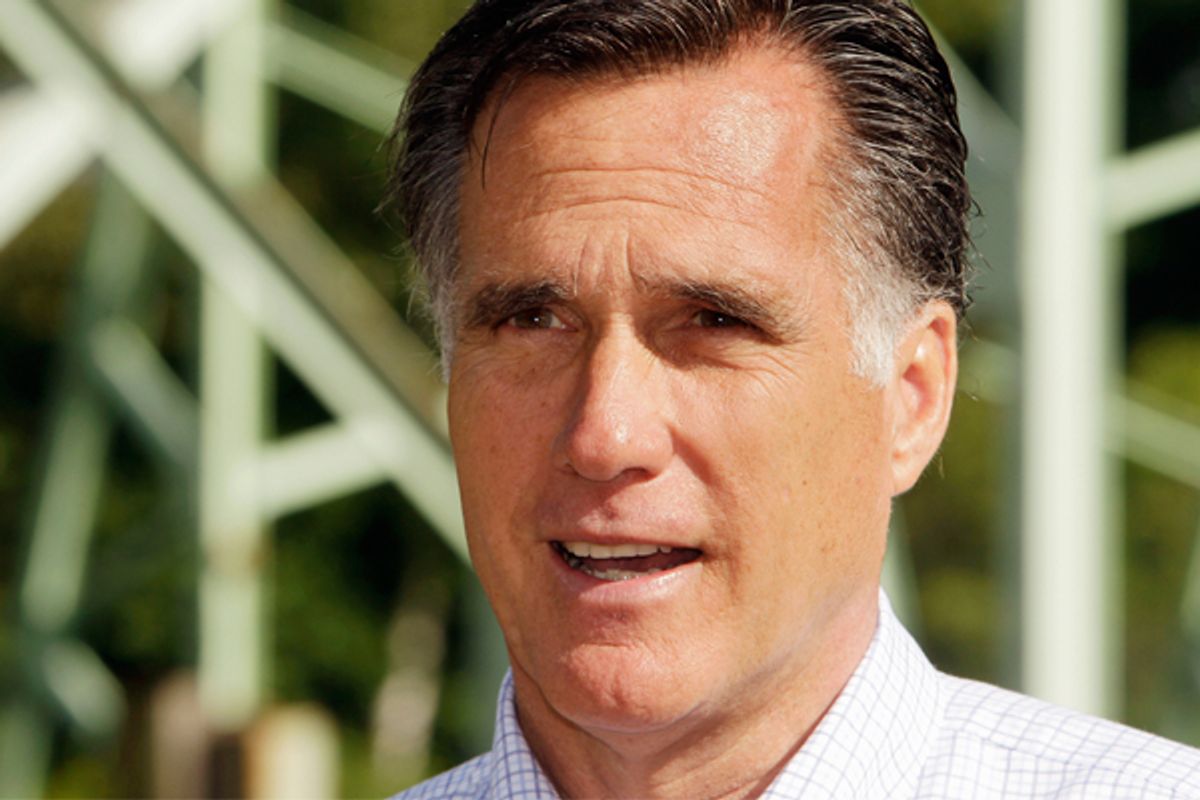

When he ran for president four years ago, there was no such thing as too far to the right for Mitt Romney -- nothing he wouldn't say or do if it held the possibility of pleasing the conservative base of the Republican Party.

This time around, as you may have noticed, things are a bit different. The Iowa Straw Poll, an event dominated by far-right activists, came and went last weekend without Romney lifting a finger, a far cry from four years ago when he invested heavily to win the event. And when a top social conservative leader in that state, Bob Vander Plaats, demanded that the GOP field sign on to his "marriage vow," Romney didn't just refuse -- he branded the document "undignified and inappropriate." He also declined to sign a pledge from a different conservative group on abortion, and stayed as far away from the recent debt ceiling debate as possible, letting one of his rivals, Michele Bachmann, use the issue to strengthen her bond with the base. While Bachmann swore at a recent debate that allowing a default would have been preferable to the deal President Obama and GOP leaders struck, Romney simply ducked the question.

The change in Romney's posture can be subtle -- he remains, on paper, a very conservative candidate -- but it's impossible to miss.

There are some obvious reasons for it. For one, Romney was brand new to the national Republican world the last time out and felt the need to compensate for the culturally moderate paper trail he left in Massachusetts, where he'd waged two statewide campaigns as a pro-choice, pro-gay rights Republican. Today, he doesn't need to strain quite so hard to fit in.

More to the point, the obvious opening for Romney in 2008 was on the right: With John McCain and Rudy Giuliani starting out as the front-runners (and with would-have-been candidate George Allen flaming out in his 2006 Senate reelection race in Virginia),the base was desperately looking for someone credible to rescue them, and Mitt tried hard -- very, very hard -- to be their man. This time, the opening is for a McCain-like establishment candidate, a role that's probably a more natural fit for Mitt to begin with.

So he's doing what establishment candidates do, trying to limit his early exposure and create an air of inevitability, and seeking to win over enough of the base to win the nomination -- but not in a way that gives his establishment backers pause about his electability. Historically, this has been a pretty sound strategy for the "next in line" Republican candidate.

The knock on Romney, though, is that this is (supposedly) a bad strategy in the political climate of 2011 and 2012. With the election of Barack Obama, the GOP base was radicalized almost overnight, as it seems to be whenever a Democrat wins the White House. But the anger of the Obama era GOP base is also unique, in that it's not just directed at the ruling Democrats but also at Republican leaders. It was this base that insisted on nominating unelectable candidates for Senate races in Nevada, Colorado, Delaware and Alaska. And it's this base, a popular line of thinking goes, that will never accept Romney in 2012 -- even if the establishment closes rank around him: There's too much doubt about his ideological purity, and his Massachusetts healthcare plan, with its individual mandate, is just too similar to "ObamaCare."

But something funny has been playing out. All year, there's been talk that Romney's campaign is facing imminent collapse -- a tailspin like the one McCain faced in the middle of 2007, except this time with no miraculous comeback. And all year, he's defied the predictions, faring far better than the doubters expected.

Think back to this spring, when the five-year anniversary of Romney's Massachusetts healthcare law prompted intense coverage of what is supposed to be his chief liability in the GOP race. Romney had avoided confronting the issue head-on, but by early May the talk was too loud for him to ignore and his campaign scheduled a high-profile speech on the subject. Content-wise, it was absolute gobbledygook, and for good reason: Romney's goal was impossible -- to frame his own law as a generally positive and fundamentally conservative advance while simultaneously blasting Obama's as a jobs- and freedom-killing atrocity. To his skeptics, this proved the point: There was simply no coherent, compelling way for Romney to appeal to the Obama era GOP base -- and to prevent it from revolting against his nomination.

But here we are nearly four months later, and while the issue has been a headache for Romney, it has hardly caused his campaign to implode. He still leads in most national polls (although a Rasmussen survey released this week did show Rick Perry grabbing the top slot), is comfortably ahead in New Hampshire, and is more than holding his own in Iowa, despite sending mixed signals about how seriously he'll contest the state.

What's happening is that the sanity strategy has actually worked well for Romney, at least so far. Part of this is because his competition has been so weak. Conservative leaders and activists may genuinely have doubts about Romney, but that doesn't mean they're ready to sign up with someone like Bachmann. And Tim Pawlenty, who seemed to at least have the potential to win over Romney-wary righties, proved himself to be a ghastly candidate incapable of exciting an audience (or pulling off an attack).

But Mitt's healthcare cover story -- which amounts to, "I hate that thing called 'ObamaCare' just as much as you and will repeal it, now just please forget about what I did in Massachusetts" -- has also mostly held up. The fact that his support didn't crater this spring suggests that Republicans are potentially willing to play along. Which makes sense, since the right's opposition to ObamaCare is fundamentally emotional and irrational in nature. Support for an individual mandate only became a crime against conservatism when Obama embraced the concept in 2009. Thus, there would seem to be room for conservatives -- if they choose to -- to continue railing against ObamaCare even while standing with Romney, who has given them a set of talking points to help them rationalize such a decision.

Granted, Romney has some new competition now, and Perry seems far more capable of using healthcare as a weapon against him than Pawlenty did. But here again, Romney may be getting lucky, because Perry is quickly proving himself to be a troublingly erratic candidate. From Romney's standpoint, the threat of Perry has always been that the party's opinion-shaping elites would find him acceptable and that, recognizing that Perry would probably be an easier sell to the base, they would rally around him. This still may happen, but Perry's first few days as a candidate have created the very real possbility that the elites will end up resisting him just like they resist Bachmann.

And if not Perry, then who else is there to derail Romney from the right? That Paul Ryan and Chris Christie are now being talked up as possible late entrants into the GOP race is confirmation of Rommey's vulnerability. But this could also be seen as proof of Romney's strength: It's nearly Labor Day and the Romney-phobes still haven't found a vehicle to stop him, and now that their great hope (Perry) may not be panning out, they're left trying to entice a second-year governor (who's virtually certain not to run) and a House member (whose intentions are harder to discern) into the campaign at the last-second.

There's still plenty that can go wrong for Mitt Romney. But if you'd described the current state of play to him back in the spring, he surely would have been happy to be where he now is as autumn approaches.

* * *

I was on MSNBC'S "The Last Word" Wednesday night and talked about the state of the GOP race with Melissa Harris-Perry:

Visit msnbc.com for breaking news, world news, and news about the economy

Shares