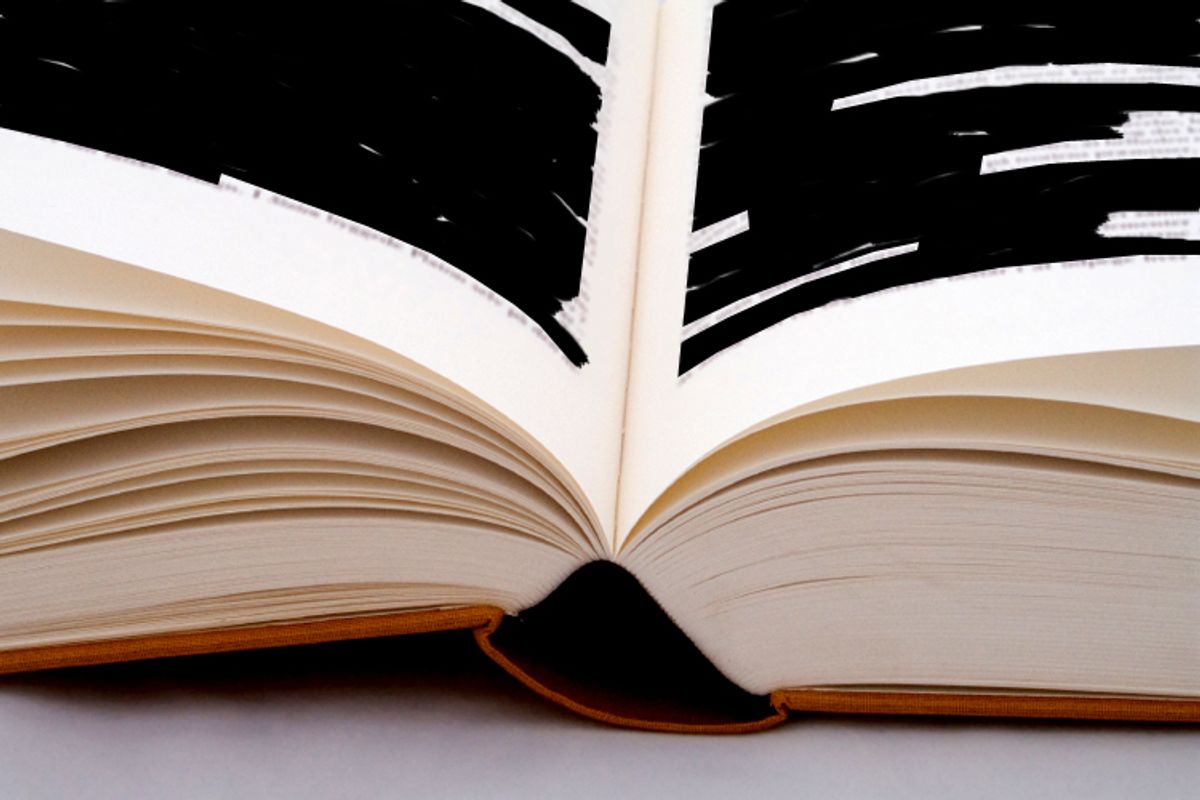

News that the CIA has demanded "extensive cuts" from a forthcoming book by former FBI agent Ali Soufan made the front page of the New York Times last week. But Soufan's isn't the only recent memoir to earn the intelligence agency's wrath by, in part, criticizing its use of brutal interrogation techniques in the decade since 9/11. There's also "The Interrogator," by Glenn Carle, a 23-year CIA veteran who was given the task of questioning a purported al-Qaida kingpin in 2002. Carle's book was published earlier this summer with many passages -- and occasionally entire pages -- blocked out with black bars to show where the agency had insisted on redactions.

Soufan has called many of the CIA's excisions from his own book "ridiculous," pointing out that some of the "classified" information is a matter of public record and appears in the 9/11 report and even in a memoir by former CIA director George Tenet. Carle had a similar experience; "The Interrogator" is laced with caustic footnotes explaining that redacted passages revealed the agency's incompetence, rather than sensitive information.

When I reviewed Carle's book in July, I made a few guesses about facts the author was obliged to leave out of "The Interrogator." Less than a day had passed before I learned that most of my guesses were wrong. Readers sent me helpful emails with links to articles supplying all the missing details, including the identity of the detainee Carle interrogated, a man he eventually came to believe was innocent.

If the CIA is trying to prevent information in Soufan's and Carle's manuscripts from reaching the public, they've obviously already failed. If anything, the agency's efforts to censor these and other books only seem likely to inflame interest in the forbidden material, which will surface anyway. Does the CIA's power to vet the writings of former government employees have any teeth in the Internet age? I decided to call up Carle to ask about his experience with the agency's censors.

Carle explained that an author negotiates the approval of his or her book with the CIA's Publications Review Board, a handful of staffers who coordinate input submitted by several agency departments. "My goal was not to piss them off to the extent that I couldn't get anything that I wanted," he said. "Their goal was to intimidate me. That was quite clear."

Because Carle knew and even respected some individuals on the board, he felt that its members were exceptionally (and perhaps recklessly) candid with him. At one point, a man standing next to him at a urinal remarked, "Don't you realize that people could go to jail for this?" referring to passages in "The Interrogator" where Carle alludes to detention and interrogation practices he regards as illegal.

The two things a former CIA officer is instructed to keep secret, Carle says, are "sources and methods." However, like Soufan, he soon discovered that the PRB had no intention of stopping there. "They told me, 'We will not allow you to take the reader into the interrogation room. We will not allow you to make the prisoner a human being. To the extent that we can, we will take out anything that gives him a personality.' I couldn't say I saw fear in his eyes, or that he was a middle-aged man. They had no right to take that out. But they did."

Like Soufan, Carle complained when the PRB insisted on cutting information from his book that was already common knowledge. Two reasons are offered for such demands. One is the "mosaic theory of classification," characterized by Carle as "one of the most harmful consequences of eight years of the Bush administration. And that is not a partisan statement." According to Carle, "The White House freaked out after Michael Scheuer's book ["Imperial Hubris" (2004), originally published anonymously] came out. They thought the CIA was out to get them. Bush said, 'I don't want anything to come out of the agency. Shut this down.'"

The mosaic theory alleges that pieces of information that may seem innocuous enough on their own -- including material that has already been cleared by the CIA -- can, when combined with similar pieces of information, present a potential threat that might be of use to the enemy. "By that rationale," Carle observed, "you should take every chemistry textbook out of every high school in America."

To get around the PRB's objections, Carle had to resort to some unusual tactics. When forbidden to describe in much detail the bombed-out wasteland surrounding one overseas prison where he worked (because this would reveal the location to be Afghanistan, a fact obvious to any informed reader), he ended up quoting T.S. Eliot. "They forced me to be more pretentious than I actually am," Carle joked.

The other justification the agency commonly offers for redacting material is that some facts, although widely known, have not been officially acknowledged by the agency or the U.S. government. If the CIA were to approve a book stating those facts, it would supposedly amount to an acknowledgment. For this reason, Carle is not allowed to write that he was posted to a position at the United Nations for over four years, although, due to the highly visible nature of that position, "every country in the world knows it." He can't refer directly to his work there "because if I do the CIA will have to acknowledged that a CIA employee was assigned to the U.N."

I asked Carle if he thought these objections were legitimate or just cover stories used to interfere with books that the agency finds objectionable for other, more self-serving reasons.

"It's absolutely both," he said. "Those are real dynamics. And they were also pretexts to harass me and injure the publication of my book. Every day that I didn't publish was a victory for them."

Further reading:

The New York Times reports on CIA efforts to censor Ali Soufan's book, "The Black Banners."

Salon's review of "The Interrogator: An Education" by Glenn Carle

Salon's review of "Imperial Hubris: How the West Is Losing the War on Terror" by Michael Schueur

Shares