Political Hollywood started much earlier than most people realize. In 1918, FBI leaders William J. Burns and J. Edgar Hoover were so worried about the power of movie stars to affect the political consciousness of a nation that they ordered secret agents to maintain close surveillance over suspected Hollywood radicals. Four years later, Bureau agents confirmed their worst fears. "Numerous movie stars," they reported, were taking "an active part in the Red movement in this country" and were hatching a plan to circulate "Communist propaganda ... via the movies."

The Cold War politicians who launched the Red Scare's infamous House Un-American Activities Committee in the late 1940s also feared the power of movie stars to alter the way people thought and acted. They understood that movie audiences were also voters, and they asked themselves: Who would people be more likely to listen to: drab politicians or glamorous stars? What if left-leaning celebrities such as Charlie Chaplin, Humphrey Bogart, Katharine Hepburn, and Edward G. Robinson used their star appeal to promote radical causes, especially Communist causes?

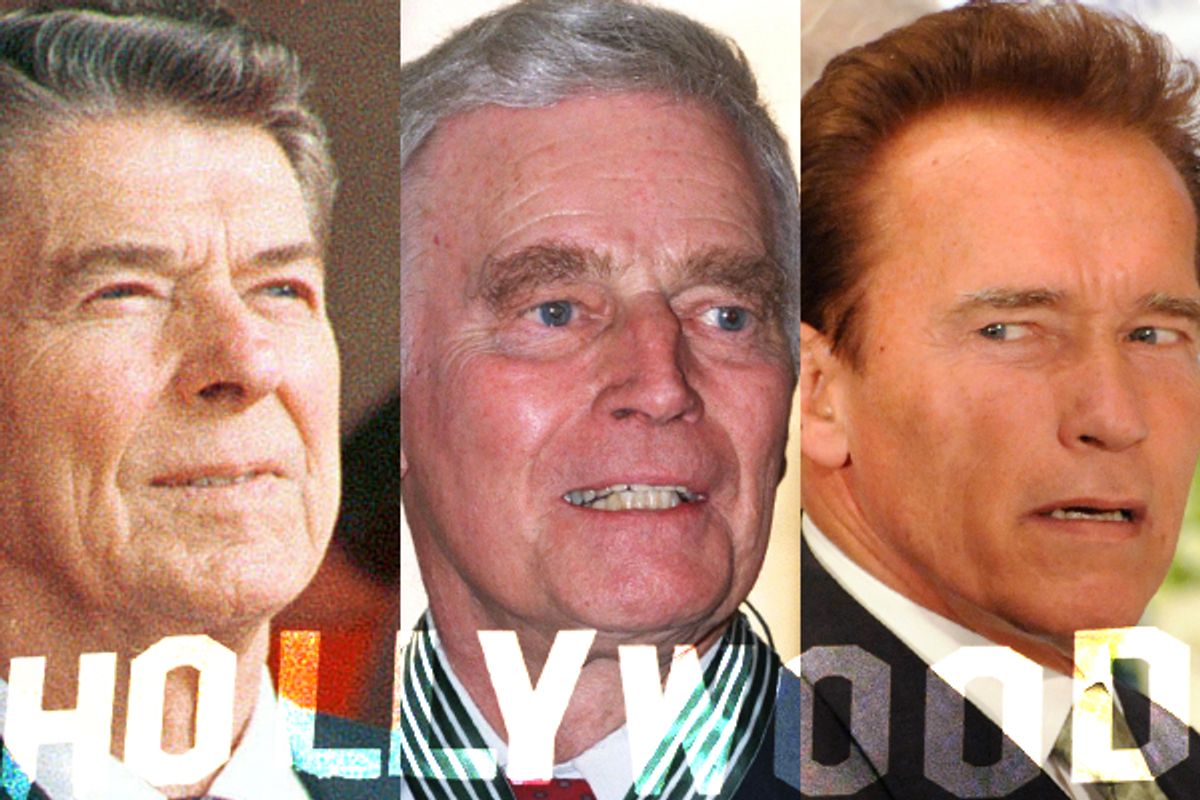

Such fears about radicalism in the movie industry reflect long-standing conventional wisdom that Hollywood has always been a bastion of the political left. Conventional wisdom, however, is wrong on two counts. First, Hollywood has a longer history of conservatism than liberalism. It was the Republican Party, not the Democratic Party, that established the first political beachhead in Hollywood. Second, and far more surprising, although the Hollywood left has been more numerous and visible, the Hollywood right -- led by Louis B. Mayer, George Murphy, Ronald Reagan, Charlton Heston, and Arnold Schwarzenegger -- has had a greater impact on American political life. The Hollywood left has been more effective in publicizing and raising funds for various causes. But if we ask who has done more to change the American government, the answer is the Hollywood right. The Hollywood left has the political glitz, but the Hollywood right sought, won, and exercised electoral power.

Can such a counterintuitive argument really be true? What did the Hollywood right achieve to merit such a claim? There have been two foundational changes in twentieth-century U.S. politics. The first was the creation of a welfare state under Franklin D. Roosevelt, a development that established a new relationship between government and the governed and crystallized differences among conservatives, liberals, and radicals. The second was the gradual dismantling of the welfare state that began under a movie star, Ronald Reagan. The conservative revolution of the 1980s could not have happened without the groundwork laid by Louis B. Mayer, his protégé George Murphy, and his protégé Ronald Reagan.

Although movie industry conservatives began wielding power in the 1920s, the Hollywood right did not emerge as a major force in American politics until after the postwar era. Once they did, their impact was tremendous. During the 1950s and early 1960s, Murphy and Reagan used their fame, charm, and communication skills to help build an insurgent grassroots constituency by speaking to conservative groups throughout the nation. The two stars articulated an ideological agenda that called for dismantling the New Deal, returning power to the state and local levels, reducing taxes, and waging war against all foes of American security -- Communists in particular. During the mid-1960s, the two former stars designed innovative campaign strategies that drew on their experiences as actors to accomplish what more established politicians like the prickly Barry Goldwater could not do: sell conservatism to a wide range of previously skeptical voters. By making conservatism palatable, Murphy and Reagan helped make the conservative revolution possible.

The movie industry began as a small-scale business with hundreds of producers, distributors, and exhibitors scattered throughout the country. There was little political engagement by actors and actresses during the early silent era because the star system was still emerging and performers did not want to risk losing their audience by engaging in partisan activities. The 1920s signaled the rise of a new type of film industry, an oligarchic studio system centered in Los Angeles and financed by some of the largest industrial and financial institutions in the nation. As the studio system known as "Hollywood" matured, so too did the focus of political engagement. With a business-oriented Republican Party dominating the national scene throughout the decade, powerful studio figures such as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's Louis B. Mayer turned to electoral politics both to meet the needs of his industry and to advance the fortunes of his favored party.

More than any other figure, Mayer was responsible for bringing the Republican Party to Hollywood and Hollywood to the Republican Party. Mayer was not a movie star, but he created stars and pioneered the uses of stardom and media for partisan ends. During his tenure as studio chief and head of the California GOP, he injected showmanship into the party's nominating conventions, showed Republicans how to employ radio more effectively, and inaugurated the first "dirty tricks" campaign by employing fake newsreels in 1934 to defeat Democratic gubernatorial candidate Upton Sinclair. Hollywood Democrats had no one to rival the power of the man who helped swing the 1928 Republican presidential nomination to his good friend Herbert Hoover.

The end of the studio system in the late 1940s and early 1950s freed actors and actresses to speak out on a wide range of issues. Just as the Depression and New Deal sparked the rise of the Hollywood left, the Cold War and the Red Scare gave powerful new life to the Hollywood right. The publicity generated by the House Un-American Activities Committee hastened the rise of the Cold War and Hollywood's Cold Warriors. Led by George Murphy and then by Ronald Reagan, a small number of ideologically driven stars engaged in conservative movement politics. Unlike issue-oriented politics, which focused on a discrete set of problems, movement politics demanded a long-term commitment aimed at restructuring the very foundations of American government.

From the late 1940s to the mid-1960s, Murphy and Reagan joined with conservative groups around the nation in an effort to overturn the most important liberal achievement of the twentieth century, the New Deal state. By reshaping the partisan uses of television and skillfully employing it to sell conservative messages, the two men reshaped American politics for the next five decades. During their political careers, Murphy, who was elected California's senator in 1964, and Reagan, elected governor in 1966, preached the politics of fear and reassurance, of dire foreign threats coupled with reassuring promises to preserve domestic tranquility. Their rivals on the left preached the politics of hope and guilt, of what America could be but how prejudice and selfishness prevented us from realizing those dreams. In the skillful hands of Murphy and especially Reagan, fear and reassurance proved a far greater motivator of voters than hope and guilt.

Charlton Heston, who began his political life on the left and gravitated to the right, was the first prominent practitioner of image politics. His monumental performance as Moses in "The Ten Commandments" (1956), and subsequent roles in which he played three saints, three presidents, and two geniuses, allowed him to forge a cinematic persona of such gravitas that he repeatedly used it to lend authority to his offscreen role as political spokesman. In the 1960s, he championed civil rights. However, following the fracturing of the Democratic Party in 1968 and the decline of its longstanding New Deal coalition, Heston moved to the right. Working tirelessly on behalf of conservative causes and candidates, "Moses," as many thought of him, used his involvement with the National Rifle Association to help swing several key states to George Bush in 2000 and thereby enable him to win the presidency.

The democratization of Democratic Party leadership that pushed Heston to the right opened new opportunities for left stars such as Warren Beatty to play a prominent role in national politics. Drawing on his skills as an actor, director, writer, and producer, Beatty served as part of the inner circle of three presidential campaigns, helping to shape the messages and media strategies of George McGovern's run in 1972 and Gary Hart's two unsuccessful bids in 1984 and 1988. Like Charlie Chaplin, Harry Belafonte, and Jane Fonda, Beatty also opened his own production company and used the screen to convey his political ideas to millions of potential voters. At a time when American politics were shifting increasingly rightward, he made two left films -- "Reds" (1981) and "Bulworth" (1998) -- that few other major actors would have touched.

The explosion of 24/7 news and entertainment media in the late twentieth century opened opportunities for yet another form of political engagement. Arnold Schwarzenegger merged Mayer's, Murphy's, and Reagan's creative use of media with Heston's use of image politics to fashion a new era of celebrity politics. Often ridiculed in the press as a political lightweight, the Austrian-born star understood what many establishment figures did not: entertainment venues such as "Entertainment Tonight" and "Access Hollywood" were not a debasement of politics but an expansion of the arenas in which political dialogue could occur, especially among Americans who tended not to vote. During his run for governor in California's 2003 recall election, the popular action hero relied on these outlets rather than on mainstream newspapers or television news shows to spread his message to voters. With few allies in the state's conservative-dominated GOP, Schwarzenegger's victory demonstrated that candidates no longer needed to have deep roots in one of the parties. Image and celebrity were now powerful enough to win an election without traditional party support.

As Murphy and Reagan, and others, demonstrated, movie stars do more than just show us how to dress, look, or love. They teach us how to think and act politically. "If an actor can be influential selling deodorants," Marlon Brando explained just before the 1963 March on Washington, "he can be just as useful selling ideas." Speaking more recently about the relative importance of Washington and Hollywood in the public mind, former Republican turned Democratic Senator Arlen Specter remarked, "Quite candidly, when Hollywood speaks the world listens. Sometimes when Washington speaks, the world snoozes."

Americans have long maintained a love/hate relationship with movie stars. Audiences connect with movie stars at an emotional level and with a sense of intimacy they rarely feel about politicians. We love stars when they remain faithful to our fantasy images of them, but we condemn them when they reveal their flaws or disagree with our politics. The public "choose the stars and then make Gods of them," director William deMille observed in 1935. "They feel a peculiar sense of ownership in these romantic figures they have created -- and, of course, an equal sense of outrage in those cases where their idols turn out to have feet of clay.

Reprinted from "Hollywood Left and Right: How Movie Stars Shaped American Politics" by Steven J. Ross with permission from Oxford University Press, Inc. Copyright © 2011 by Steven J. Ross.

An eminent historian of film, Steven J. Ross is recipient of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Film Scholars Award and author of the prize-winning book, "Working-Class Hollywood: Silent Film and the Shaping of Class in America."

Shares