There are two books grappling for predominance in Stephen Greenblatt's "Swerve: How the World Became Modern." The most interesting is the story of how a school of thought -- Epicureanism -- survived the downfall of the classical world and has woven itself through Western culture despite being antithetical to the dominant beliefs of that culture for much of its history. The most splendid manifestation of Epicurean ideas, a long Latin poem by the first-century Roman philosopher Lucretius, titled "De rerum natura [On the Nature of Things]," was nearly lost, like so many other Greek and Roman texts. Fortunately, as Greenblatt relates, a Florentine book hunter named Poggio Bracciolini discovered a manuscript in a remote German monastery in 1417, had it copied and returned it to circulation among the collectors, writers, artists and thinkers who would become responsible for the Renaissance.

If you think Epicureanism means extravagant self-indulgence, think again. Lucretius was a follower of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus, who did indeed argue that pleasure is a sign of the good. But Epicurus also wrote, "we do not mean the pleasures of the prodigal or the pleasures of sensuality." Another of his followers, Philodemus, explained that it is impossible to live in true pleasure, "without living prudently and honorably and justly, and also without living courageously and temperately and magnanimously, and without making friends and without being philanthropic."

Moreover, the Epicureans were materialists who believed that the human soul does not survive the death of the body and that no gods preside over our existence, doling out rewards and punishments. They understood the universe to be infinite and to be composed of tiny particles called atoms. In "On the Nature of Things," Lucretius argues that everything around us is the result of (in Greenblatt's words) "an unexpected, unpredictable movement of matter," causing atoms to clump together or break apart, forming all the recognizable objects of the world. Living things themselves emerged in this way, and are in a process of continuous change as a result of untold numbers of chance "swerves."

These views are remarkably close to those of contemporary secular humanists, right down to an approximation of Darwin's theory of evolution via random genetic mutation (although, of course, the ancients did not know about genes or mutation). "Swerve" illustrates that this way of seeing the universe preceded the scientific revolution that ultimately confirmed it, which may or may not give today's secularists a boost. (Confirmation bias, anyone?) Above all, Epicurus and his followers conceived of an ethos that required no supernatural enforcer threatening to condemn the wicked to eternal torment. The Epicurean good life is a good life in both respects -- enjoyable because it is moral, prudent and honorable. It is also a life devoted to celebrating this world, not the next.

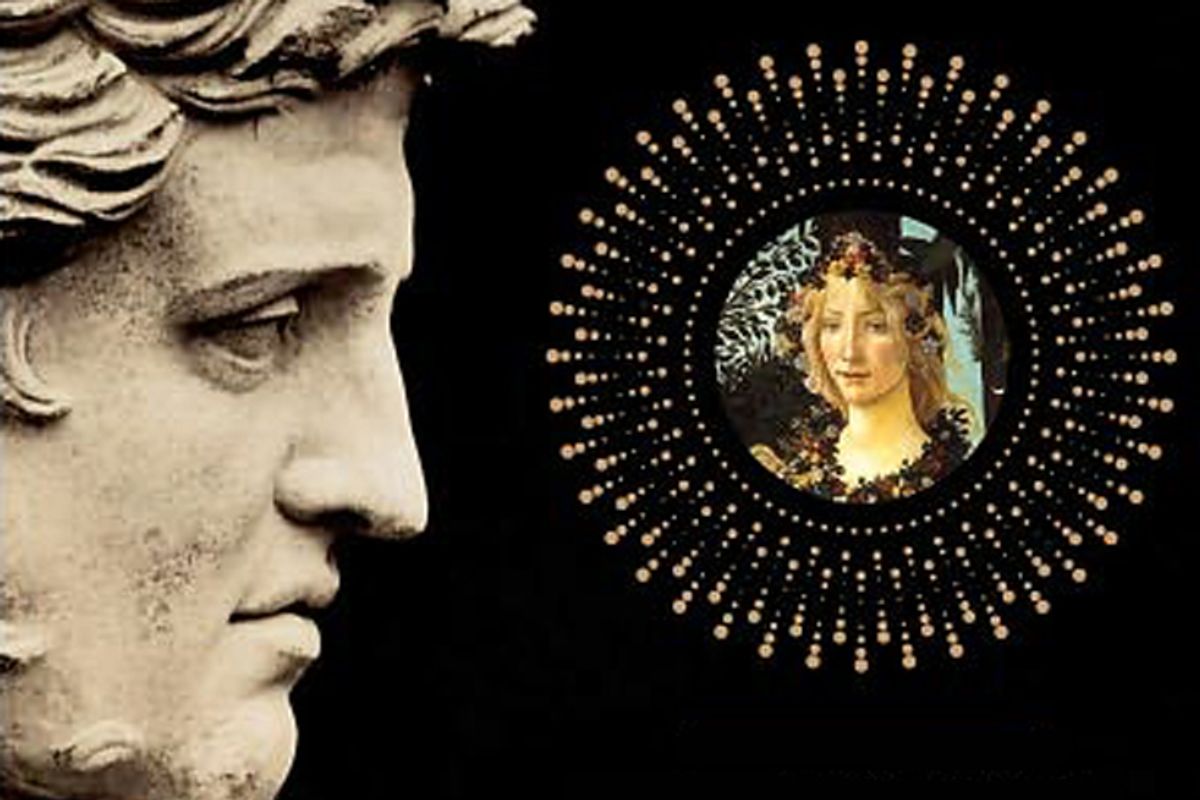

It's fascinating to watch Greenblatt trace the dissemination of these ideas through 15th-century Europe and beyond, thanks in good part to Bracciolini's recovery of Lucretius' poem. Because it was written in the most exquisite Latin (and because the author was a pagan who didn't know any better), "On the Nature of Things" found a place in many respectable libraries despite containing ideas that got the likes of Giordano Bruno burned at the stake. Lucretius probably had the most marked influence on Montaigne, but Greenblatt claims to see traces of "On the Nature of Things" in everything from the paintings of Botticelli to the plays of Shakespeare.

At times, all this seems a bit of a stretch, and that's where the second narrative in "Swerve" comes in. Perhaps it's due to a publishing industry imperative dictating that you can't write a book about a historical subject without claiming that it "changed the world." That revolutionary model certainly jibes with a hoary narrative familiar from my elementary-school social studies courses, an orgy of Renaissance worship whipped up by Kenneth Clarke's "Civilization" (the TV series and the book), in which the Middle Ages was invariably depicted as an inert cultural wasteland presided over by a philistine church.

This view of European history is by no means shared by all or even most historians, as Greenblatt himself surely knows. At times "Swerve" feels downright distorted, bending the facts to fit this Clarkean scenario. That takes some elbow grease, especially when you consider that the introduction of Lucretius' poem "reinvigorated" and made more creative a medieval Italian literature that had already produced Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio. The post-Lucretius lineup is a lot less impressive, which may be why Greenblatt emphasizes the painters of the Renaissance instead. How a rediscovered poem could revolutionize a region's visual arts without much improving its written ones remains a puzzle.

Greenblatt is no stranger to finessing the historical record; his last popular history, "Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare," spun the handful of facts known about the playwright into a highly speculative but supremely charming meditation on his life. "Swerve" is just as beguiling, even if Poggio Bracciolini makes for a less compelling protagonist (but then, who wouldn't?). I can't help wishing that Greenblatt were as forthright about the liberties that he's taken in this book as he was about the speculation in "Will in the World," but a better acquaintance with Lucretius, Epicurus and Bracciolini more than compensates for that minor vexation. I see more evolution than swerve in the journey of European culture, but the trip is pretty darn scenic either way.

Further reading:

Salon's review of Stephen Greenblatt's "Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare"

Shares