Sometime after the end of the modestly enjoyable "Becker" and before the short run of the more modestly enjoyable "Help Me Help You," Ted Danson disappeared -- only to reemerge with completely white hair. Like the bleached reincarnation of Gandalf in "The Lord of the Rings" or Richie Tenenbaum's prodigal hawk in "The Royal Tenenbaums," it was evident that something profound had happened, that the actor has attained some new wisdom. Joining the chorus of angry (celebrity) gods punishing Larry David on "Curb Your Enthusiasm," we began to see a new Danson: no longer the affable Sam from "Cheers," he became at once looser, less predictable and touched with something resembling gravitas.

Danson had become a dangerous actor. On FX's "Damages," we saw the white-haired wraith create an almost lovable monster in the form of Arthur Frobisher, all kind eyes and awkward rage. As Frobisher broke a man's nose with a Pinewood Derby car, defrauded his employees, and snorted coke with prostitutes while calling in hits from the backseat of his SUV, Danson spent a phenomenal season out-acting Glenn Close on her own show. Then, on HBO's stoner noir "Bored to Death," Danson reemerged as a comic actor with an impeccable sense of timing and a melancholy sensitivity toward death and dying. Danson's George Christopher is a poignant slapstick exploration of what it means to get old. But the performance is also a kind of statement, on Danson's part, about what it means to become an older actor.

Actors age in idiosyncratic ways. The White Period of Ted Danson most resembles that of Bill Murray, who, since his resurrection as an upper-middle-aged curmudgeon amid pubescent scoundrels in "Rushmore," has become an unlikely muse for indie writers and directors. "Garfield" aside, Murray has grown choosier and more obscure in his AARP days, but his performances have gained a new strength. The fast, fluent one-linerism of his youth has morphed into the funniest and saddest deadpan on the silver screen.

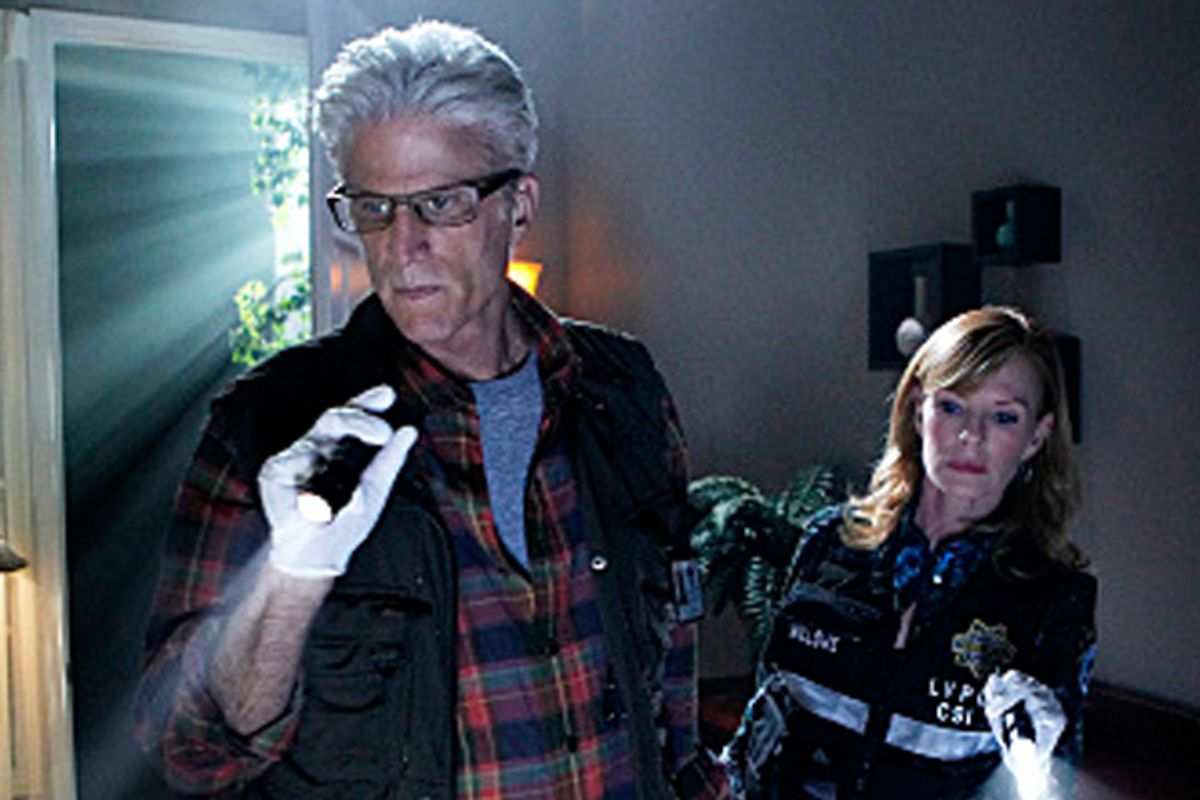

Tonight, however, Danson makes a puzzling return to prime-time network TV to anchor "CSI: Crime Scene Investigation," one of CBS' most profitable -- and, in many ways, most conventional -- series. Why would Danson make such a confounding choice? Is this his "Garfield" moment?

The first episodes of the new season don't offer much help. The primary impediment to figuring out what Danson is doing on this television show lies in the nature of the show itself. The ur-series of the scientific crime procedural, "CSI" is a show that does not need actors. Revelations come through forensics, not necessarily intuition, cunning or intellectual derring-do -- though Sherlock Holmes was a master of forensic science, his investigations benefited from a bit more panache and a bit less automation. And so, at best, the CSI investigator becomes a supporting player to the hocus pocus of blood and semen analysis. Actors like William Petersen and Laurence Fishburne have worked valiantly to establish relatable characters on the show, but "CSI" is no place for charismatic Sherlockery.

Without overly lionizing Ted Danson -- who, in his prime, was the most mainstream of mainstream television actors -- as an avant-garde instigator, it's hard not to entertain the notion that this might be a piece of James Franco-style conceptual art. Within the bounds of the material, Danson is doing fun, off-the-wall work -- his character is implied to be smoking pot off-hours -- but he is surrounded by a well-chiseled, anonymous supporting cast trying to act as hard as they can.

What seems more likely is that Danson is making a prudent move to secure himself late-career recognition. Danson was nominated for an Emmy for his astounding performance on "Damages," but he lost to his costar Zeljko Ivanek, and most people seem content to overlook the great work being done by pretty much everybody on "Bored to Death." In this context, it’s entirely possible that Danson sees the CSI franchise as an opportunity to take advantage of the actor's recent renaissance in order to transform the series from bland procedural to something more character driven, punchy and, well, Emmy-worthy.

In the post-"Sopranos" decade, it is a commonplace assumption that the only really serious quality television is happening in the form of non-network serialized narrative. Even AMC's infuriating procedural "The Killing" went out of its way to avoid the episodic by stretching one case across the length of a season.

But there are exceptions. Fox's "House" is a likely model for the Danson-era "CSI" makeover. The show is still structurally an episodic procedural -- each episode focuses on a new patient, afflicted with a mysterious, multistage illness that might be, but probably isn’t, lupus -- but each episode is a veritable showcase for the sad features, romantic potential and convincing American accent of its star. And though Hugh Laurie has yet to snag a best actor Emmy, the show adapts and evolves along with his performance in a way that few network shows, especially genre shows, are able to do.

While Laurie's cranky savant on "House" is a clear analogue to Danson's new work on "CSI," this formula has also worked for recent Emmy-laureate Julianna Margulies' network prestige drama, "The Good Wife." The hybrid serial has become the gold standard for network drama, and it's proven to be an extremely wise mid- to late-career move for Laurie and Margulies. With "CSI," Danson is in a position to get the same kind of notice without the hassle of trying to sell a new series.

Of course, "CSI" is not already a showcase for central talent. Both Laurie and Margulies are surrounded by incredibly talented supporting casts, from Robert Sean Leonard on "House" to the court reporters on "The Good Wife" who do more valuable character work than most of Danson's cohort in the CSI unit.

But this brings up another crucial element of Danson's White Period, and that is his knack for association. Larry David, Glenn Close, Zeljko Ivanek, Zach Galifianakis, Jason Schwartzman -- Danson's late career is as defined by proximity to other great performances as it is by his own performance. His best scenes, in fact, have most often been shared with other equal partners, from the explosive Ivanek on "Damages" to Galifianakis' narcissist clown on "Bored to Death." As it turns out, in addition to becoming dangerous, Danson has become a dynamic ensemble player. And while he brings that energy to "CSI," there is considerably less opportunity for charged give and take. James Franco, we all know, is one kind of actor on "Freaks and Geeks" and a whole other kind of actor on "General Hospital."

This focus on the ensemble is the defining feature of Danson's White Period, and it makes the actor a surprisingly timely figure for this cultural moment. Over the last few years, television has been dealing with aging in remarkably direct and occasionally embarrassing ways. Last year's season finale of "Mad Men" -- spoiler ahead! -- ended with Don Draper's impulse-buy selection of a much younger bride, thus revealing the show's earlier plotline about Roger Sterling's own trophy wife to have been more than an elaborate punch line. And more recently, FX's "Louie" has trained a gleefully grotesque eye on the physical and emotional deteriorations and regrets that accompany aging. Louie himself is compulsively self-effacing, and the show's theme song even pointedly ends: "Louie, Louie, you're gonna die." To age on television in the early 21st century is to face, alone, the imminent and irrevocable destruction of the ego.

Ted Danson has been quietly at the forefront of this discourse for years now. Danson's homicidally humbled and lonely Frobisher on "Damages" set the tone for that show's still incisive study of friendship and power. To watch the fall of Arthur Frobisher was to watch the tragedy of friendless old age and the terror that comes in the face of being forgotten. In a different register, George Christopher on "Bored to Death" feels the same terror as Frobisher but finds salvation in his league of ordinary gentlemen and the joy of carousing with his buddies in a used Subaru.

And so both Danson and his characters, of late, have been animated by the desire for a good ensemble. This, I think, is at the heart of the actor's perplexing move to "CSI." It's hard to know whether this gamble will pay off, and especially if this particular ensemble can grow around this particular actor. Regardless, it's a decidedly optimistic show of faith in network genre television -- and a real statement against the monolithic "Sopranos" model of serial narrative.

Shares