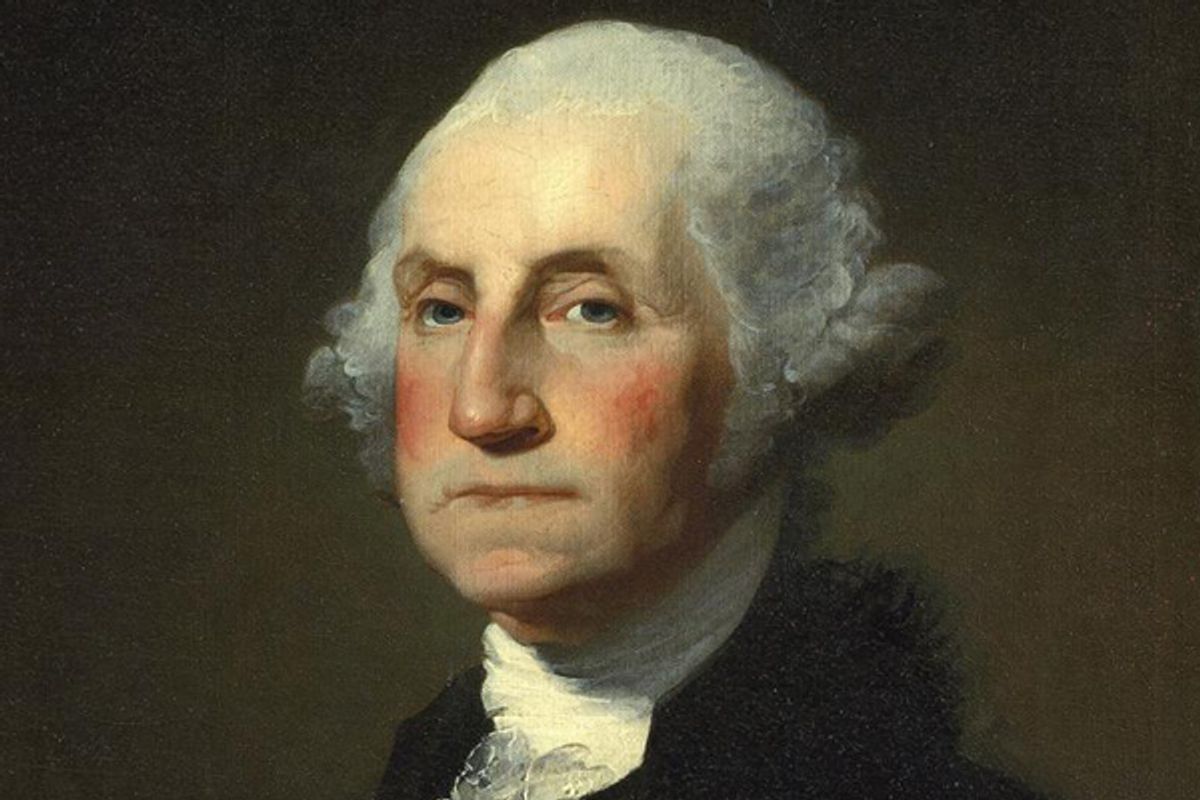

When George Washington wrote of an American "Union" with "a government for the whole," his vision was radical, perhaps foolhardy. Such a thing had never existed among a diverse people, across a vast continent, with no established royal or military authority. The Union of politically empowered citizens that Washington described was an aspiration more than a reality. It was a dream after two difficult decades of revolution, war, and reconstruction.

Washington's vision was prophetic. He was ahead of his times. His contemporaries, especially in Europe, expected tyranny, anarchy, or the return of foreign empire in North America after the British defeat. Eighteenth-century thinkers had few models of a good government "with powers properly distributed and adjusted." They had even fewer models of a strong government that became a "guardian" rather than an oppressor of liberty.

George Washington's eighteenth-century radicalism evolved into the twenty-first century's conventional wisdom. The success of the American experiment in building a prosperous and democratic Union discredited other options. When Washington wrote his words people advocated many kinds of government: monarchy, theocracy, confederation, empire, city-state, and even small republic. Representative government for a large, diverse, and united population living in a dispersed but discrete territory -- that became the contemporary standard for the modern "nation-state." It was almost nonexistent during Washington's lifetime. In its early American formation, the political institutions that we now take for granted were an eccentric experiment -- an "exception" to the common arrangements of the era.

Two hundred years after Washington, American exceptionalism became the normal expectation for citizens. The United States proved that large, diverse, and united societies -- "nations" -- could achieve more than their fragmented counterparts. The United States also showed that the first president's claims about the virtues of a representative government were well founded. A powerful government of the people did more for the people, and it was generally more stable than its predecessors. The American model stood out for its unity and its representativeness.

Although many Americans -- including women, African Americans, and others -- did not initially have full rights of citizenship, the society they inhabited encouraged more popular participation in politics than any late-eighteenth- or nineteenth-century counterpart. Politics was part of the nation's common culture. The state birthed from rallies, debates, and conflicts claimed legitimacy from its roots in the street, not the gentleman's club.

By the twentieth century virtually all governments organized themselves as nation-states. Dominant state institutions claimed legitimacy because they spoke for the people -- not divine authority or a borderless ethnicity -- in a particular place. Modern political power was nation-state power. National populations claimed particular rights and privileges because they were constituted in a single state. The ties between nation and state became symbiotic and near universal.

Political power centered on territory, institutions of control, and repertoires of consent -- all symbolized by the flags and passports distributed to mark simultaneous identity and authority. The unbound merchant traveler of an earlier age became the Chinese citizen regulated by the Chinese government, or the German citizen protected by both the German and European Union governments. When entering the borders of another nation-state, one must show one's passport to prove that one is a bona fide part of the larger nation-state system, with clearly defined loyalty and responsibility. If you do not have a nation and a state, then you have neither a homeland nor a right to travel safely beyond. If you do not have a nation and a state, you do not count in the modern world.

The antiterrorist measures implemented across the globe since 11 September 2001 to control the free movement of peoples, weapons, and products have reinforced this nation-state system. Borders are rigidly policed by states. People are closely categorized by nationality. "National security" takes precedence over all other claims. Nongovernmental organizations (like Amnesty International) and intergovernmental institutions (like the United Nations) continue to exert important influence, but they are tightly tied to nation-states for their resources, recruitment, and leverage over policy. International advocates of human rights, environmental protection, and religious freedom are most effective when they work within and between nation-states, not as alternatives to nation-states. The same is true for multinational corporations. Although they operate globally, they remain regulated by nation-state laws and organizations composed of nation-states, especially the World Trade Organization. The world of the early twenty-first century is a world dominated by political "Unions" that resemble Washington's farsighted conceptualization. He would be surprised only at their uniformity and their near universal spread.

The United States did not create this system alone, but it contributed to its development and expansion. Washington's calls for "Union" in a new country began the wider diffusion of the nation-state as the foundation for political power in the modern world. Other forms of political authority declined as the American-inspired version rose. The United States influenced this process by model, by rhetoric, and often by direct policy. Since the eighteenth century, Americans have sought to create a world that would be "safe" for their form of government -- a world that would adopt harmonious political institutions, despite continued cultural diversity.

That is, of course, the deeper meaning of pluralism: "unity in diversity." It was the foundation for Woodrow Wilson's famous -- perhaps infamous -- call for a "League of Nations." Franklin Roosevelt followed with plans for a "United Nations." His successors have furthered this process through the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the European Union, the World Trade Organization, and other international bodies that define power around nation-states -- not races, religions, or other markers of identity. American pluralism is the pluralism of nation-states. Modern globalization is the globalization of nation-states too.

There are very few substitutes for this system in the twenty-first century. If you want respect as an international player, you must be a nation-state. Compare the circumstances of Egyptians, who have a recognized nation-state, and the Kurds, who do not. United peoples represented by strong institutions in a given territory can claim voice in global negotiations. Those who are not united, not represented, and not identified with a particular place get little attention. Political sovereignty in the modern world is based on national identity and effective state governance. Other forms of authority get little recognition. Politics has become less diverse since the eighteenth century.

President Barack Obama's description of contemporary American foreign policy reinforces this point. When he echoed George Washington, extolling the United States "as one nation, as one people," his words were neither original nor revolutionary. They were common to American political statements. Obama was describing the obvious, articulating the standard clichés, appealing to American triumphal self-regard. His words were ritualistic, repeated by nearly every president. United action in a strong nation-state had become the touchstone for protecting security and liberty, especially after attacks by vicious nonstate actors. Building stable nation-states in regions filled with "tribal" hatreds and "failed" states -- both of which sponsored terrorist activities -- had become the most accepted approach to ensuring peace and prosperity. This is what Obama meant when he spoke of an American "creed that calls us together, and that has carried us through the darkest of storms."

Applying the wisdom of accumulated American experience, Obama and most of his listeners believed that the suffering citizens of Afghanistan, Iraq, and other countries would live better if represented by institutions that governed local groups "as one nation, as one people." Effective nation-states in those countries would establish security, they would help their citizens, and they would keep extremists out. They would also serve American and other international interests in stability, access, and profit. Afghan and Iraqi nation-states were the solution to terrorism, as they had been the American solution to other threats in prior decades. From the founding to the first years of the twenty-first century, the history of American nation-building repeated itself.

Obama pledged that the United States would continue to support nation-building abroad, despite all the other demands on resources at home:

Our union was founded in resistance to oppression. We do not seek to occupy other nations. We will not claim another nation's resources or target other peoples because their faith or ethnicity is different from ours. What we have fought for -- what we continue to fight for -- is a better future for our children and grandchildren. And we believe that their lives will be better if other peoples' children and grandchildren can live in freedom and access opportunity.13

Nothing could be more American than to pursue global peace through the spread of American-style institutions. Nothing could be more American than to expect ready support for this process from a mix of local populations, international allies, and, of course, the United States government. Between the presidencies of Washington and Obama, nation-building became the dominant template for political change among Americans. Matched with the growing power of the United States, this template gained unparalleled global force.

The most difficult part of policy is making change. Time pressures, resource constraints, cultural diversity, bureaucratic red tape, and the fear of the unknown reinforce resistance to reform. This is true within both rich and poor societies. For this reason, many leaders give up. They satisfy themselves with efforts to work on the margins, to preserve rather than to progress. This is often called pragmatism, but it really is not. It is the politics of least resistance and the tolerance of the lowest common denominator. Never understimate how risk-aversion prolongs failed policies, including wars and other conflicts. To sue for peace and invest in reconstruction -- that is often the most uncertain and unsettling endeavor.

Americans have made more wars than many others, but they have also tried more often than anyone else to build nations after battle. That is why I call Americans "a nation-building people." That is why Americans are continually trying to change societies. That is why American policies are so unique, so interesting, and sometimes so baffling.

Jeremi Suri is the Mack Brown Distinguished Professor for Global Leadership, History, and Public Policy at the University of Texas at Austin.

Excerpted from "Liberty’s Surest Guardian: American Nation-Building from the Founders to Obama" by Jeremi Suri. Copyright 2011 by Jeremi Suri. Published by Free Press.

Shares