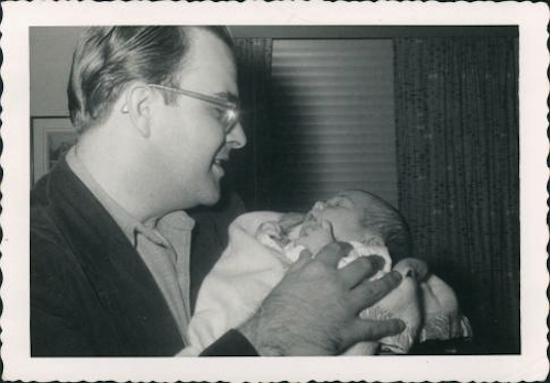

Neither of my older brothers nor I have many fond memories of our father. My brothers, who are 11 and 12 years my senior, tell me that when I was 3 years old I was so terrified of him that on the rare occasions he would come home I ran out into the woods behind our house and hid. They had to come out and find me.

My brothers remember waking up to the sounds of drunken men brawling in the living room — my father and the husband of some woman. It’s no wonder why someone else’s husband would be trying to beat up my father; he was a notorious womanizer. He even lost his job at a women’s college in South Carolina for having an affair with his student.

Dad left when I was 3, and he rarely paid any attention to us kids. He was a musician, but he took no interest in my two brothers who both played in one of the country’s best high school marching bands. One brother got a full scholarship to Eastman School of Music; the other ended up playing trombone in the prestigious Navy band. My father never attended a single one of their performances.

My father was stingy with both money and affection. I can sum up the things he gave me over the years as follows: a child-size lounge chair when I was 7, two books he no longer wanted when I was around 15, a check for $75 when I turned 17, and two ratty little stuffed lions for my daughter when she was a baby. He never saw me in any of my plays or ballet performances. We never did anything together.

As adults, my brothers and I tried to cultivate some kind of relationship with him. Whenever we would see him, he would make a vague reference to our inheritance. “When I die, whatever I have goes to you three children,” he said over and over. I figured he was trying to make up for the fact he never gave us anything when we were kids.

But, even if he’d intended to atone for his treatment of us, he grew completely senile in his last years. So we were disappointed but not surprised when upon his death everything he had (which was not all that much) went to his widow. We were more surprised when she refused to allow us even the smallest token — a book or some other memento or our father. When I was younger and knew I wanted to be a writer, I would gaze longingly over my father’s extensive library during my rare visits, afraid to ask for one.

But the biggest shock of all came at his memorial service. The man who played the piano during the service wept copious tears. He was about my age, maybe a few years older. My brothers and I had no idea who he was. After the service, we mingled with the guests downstairs. Several had been friends of both our parents. There were pictures posted of my dad in his jazz combo. He looked cool with his black goatee and sideburns; he could have been one of the Beats. I felt a sense of loss that I had been so shut out of his life.

Then the man who had been playing the piano came up to us and, after explaining that my dad had been his piano teacher for many years, said, “He was such a wonderful man. He was like a father to me, and he told me I was like a son to him.”

My brothers and I were speechless. I finally stammered, “I’m glad he had that experience with someone.”

He told us how Dad and his wife Mary had given him several hundred books they no longer had room for. He hadn’t known what to do with them so he gave them to the library.

My brothers and I turned away from the man. We were a bitter three, and now we understood how my mother must have felt that one time before I was born when she was taking my brothers to the beach and she looked over at a car next to her at the stoplight. There was my father with another woman and her children, heading to the beach.