Two years ago, Time magazine named Martin Lindstrom one of the 100 most influential people in the world, explaining that he was among "the first brand experts to understand the biology of consumer desire." A marketing guru who has worked with some of the most powerful corporations in the world -- from Disney and McDonald's to Procter & Gamble and American Express -- Lindstrom is clearly very good at what he does.

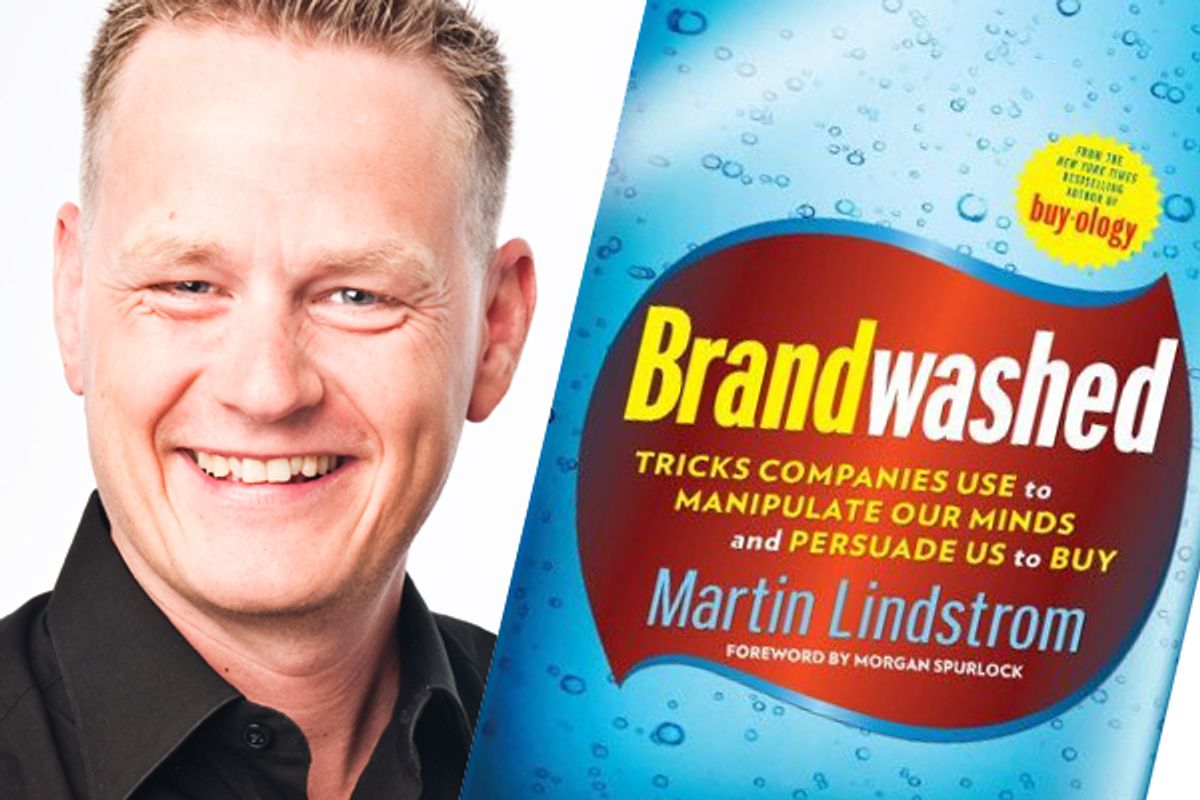

But according to the biographical note at the end of his new book, "Brandwashed," Lindstrom "opened a new chapter" in his career around the same time he was featured in the pages of Time. "Disheartened by much that he had observed on the front lines of the branding wars for the past two decades," it says, "[Lindstrom] decided to turn the spotlight inward and reveal all the tricks and traps he'd seen along his journey from 11-year-old LEGO enthusiast to one of the globe's foremost marketing experts. His goal? ... [To help us make] smarter, more informed decisions about how we spend our money."

Indeed, it might not be the "Kitchen Confidential" of the ad world, but "Brandwashed" does offer insight into some of the more colorful tricks of Lindstrom's trade. Did you know, for instance, that babies can begin to recognize product jingles before they're even born? That the fruit you buy in supermarkets is sometimes more than a year old? Or that the Muzak you heard the last time you went shopping at the mall was "very carefully and deliberately selected" for you, based in part on demographic data collected by the establishment you were visiting?

Lindstrom's book might fall short of scaring you into a full-scale brand boycott (something Lindstrom himself has attempted, without success), but it will likely make you a more skeptical consumer. In a phone interview, Lindstrom answered some of my questions; what follows is an edited and condensed transcript of our conversation.

Can you start by saying a little bit about your background? In particular: When and why did you decide to be a consumer advocate as well as a brand advisor?

First of all, I began my own advertising agency when I was 12 years of age, so I've been into the industry my whole life. It's become clear to me over the years that the industry and corporations are getting more and more greedy and more and more desperate to generate revenue, and I feel at some stage it's my duty as an individual advising companies to draw a line in the sand, and to basically question some of the stuff they do. Because, actually, not a lot of people are doing that -- particularly not from inside.

[Some corporations today] are going so far that I personally do not feel comfortable about it. In order to make things change, I have two options. I can stand on the sidelines and shout and scream at the companies, and say, "You idiots!" -- but I'm not sure I'd get so much out of it. The alternative is to work from inside and actually start to represent the voice of the consumer in a much more prominent way. That's what I believe in, because I believe that will actually generate a much better chance for a change. And if I then have the army of the consumer with me -- so I'm not just one voice, but I have a whole backup choir -- well then, my voice becomes so much stronger; when the executives are squeezed into a corner, making some pretty tough decisions on ethics, then they will actually listen to me, because they know I have influence [with the consumer].

That's really the reason why I wrote "Brandwashed" -- because, to be honest, if I were to write a book called "Ethics," first of all, no one would read it, and secondly, the industry probably wouldn't listen to it at all. If I write a book for the consumer, then I think there's a good chance that the industry will feel huge pressure; once -- hopefully -- this book becomes popular, they will have to change. Someone needs to say it, and so far, no one has.

You do still work on some branding projects, though, right?

I do. But I'll give you some examples of how I work on those projects, just to put things into perspective.

First of all, I do not work on every project in the world; I'm incredibly critical. In my last book, "Buyology," I attacked the tobacco industry. My mom is almost dying from smoking, and of course that's taught me a lot. As a reflection of that, I started to go against the tobacco industry about four years ago. I'm not sure it's 100 percent my fault, but certainly I had a strong influence [on the decision to put new] health warnings on North American cigarette packs. Also, I managed to put so much pressure on Philip Morris last year and this year that they withdraw their $120 million sponsorship for Formula One -- that I'm actually pretty proud of. The tobacco industry has contacted me 18 times in the last year to ask if I wanted to work with them. And I don't need to tell you, the answer has been and always will be "no."

Other companies, like large fast-food companies, have also contacted me -- and here's my response to them: I say to them, listen, I'll be happy to work with you guys if I'm allowed to change the food, and make it healthy. And that's in fact what I [have done]. So in the case of one of the [companies] out there producing meals for kids (which I don't need to tell you are deeply unhealthy), I said to them: I'll work with you guys if you will give me the money to change the product, and not only that, to make sure that that product becomes so popular that kids will start to eat vegetables and bananas and cucumbers and all the boring stuff (in their mind). That's actually what we did. In Europe, I've helped some of those companies to change their entire food menu. And when that happens, I feel good about it. Because then I'm helping mothers and families to make sure that their kids in fact are changing their eating habits. Now, I would not be able to change it by saying, "Close down your brand," because they won't do that. And I cannot help them by just being silent. But what I can do is to use the power of the brand to change consumers' behavior -- and the company's behavior -- so they eat more healthily. ...

I wouldn't do things to consumers that I wouldn't do to my own kids, and to my own family. That's my golden rule, and that is what's driving my behavior.

So you feel your influence on the industry is a mandate -- that you should help consumers where you can.

Yes. I have a door straight into the boardroom in most of the major companies; it's a mandate I should use. Just to shut the doors and [insult the executives] won't get me very far. It will sell a good book, and that's it; it won't change the companies.

Here's my argument to companies. I'm basically saying: Listen, you will have to change because the consumer -- us -- we will over time become the owner of your brand. ... The hold of the consumer is so powerful that we can tear down a brand in days, or we can build up a brand in days. And if you don't buy into that way of thinking, you won't be around 10 years from now, so you'd better change. But it also requires you to step up and change some of your ethical guidelines: Clean up your products; clean up your focus on the environment and use of eco-friendly terms (which, nine times out of 10, are lies), or whatever it is. And that's where I try to use my influence -- in order to make them listen and change.

What's your goal with this book? Is it to change people's habits? Or simply to inform them about marketing tactics they might not otherwise have noticed? Because, while I was certainly surprised by some of the things I read, I have to say that I'll probably continue to buy all the products I bought before.

Well, let me put it this way. Of course I can't change people's entire behavior with one book. But if I can just change you 1 percent -- and if I can make companies change 1 percent -- I think it's worth it. Just 1 percent is fine with me. Perhaps when you buy a product [from the supermarket] next time, rather than being fooled by the fact that it looks fresh, you'll be very skeptical about its presentation -- the ice, the dripping water -- and actually, you'll make a more clever decision. Then I'm happy. I'm happy if, next time you surf on the Net, you actually know how your information will be used, and you're just a little bit more careful. If I change your behavior 1 percent, and I do that with many people in the population, haven't I succeeded? I think I have.

Now that you mention it, I'm sure there's at least one detail I won't forget: You say that the average supermarket apple is more than a year old. Please tell me that's not possible!

It is possible. A lot of apples are stored in huge warehouse where there's a special type of air that can make them last for a very, very long period of time. Remember also that lots of apples have preservatives on them -- they have preservatives in the whole way they've been maintained and grown, so at the end of the day you have apples that are seriously old ([it's the same with] potatoes, and whatever else). You also may recall from the book that we choose things like apples, bananas and carrots based on their colors -- and it's all a hoax, you know? It's us believing that that color is the correct color; [the reality is that these fruits] are designed, color-wise, to look like the color we would prefer. Whereas a greener type of banana is much more healthy. I think these are things we just need to be aware of. I'm not sure how much it's going to change you, but I'm pretty certain that you would across the board probably be more skeptical [after reading my book].

At one point, you say you traveled to Russia in order to develop a new brand of vodka. What interested me most about this particular project was how much of it seemed to involve anthropological elements: Discovering the habits of people from various regions, inventing and marketing new "rituals." In your line of work, what would you say is the split between research involving anthropology and research involving neuroscience?

In my mind, it's the same. And with the Russian case, which was one of those cases where I was on the borderline for should I do it or not, I ... said to [them]: Listen, if I'm going to do this, I'm only going to do it because it would be a way for me to make people drink less and drink more healthily, if you could say that. ...

[In Russia,] the average life expectancy for a man is 56 years of age -- and I've seen the most nasty things you can possibly imagine in Siberia. [Still,] you need to be realistic. If I pull the plug on vodka, I'm sure that the country will go down; if you can't beat them, join them, which is a much more smooth way to change life expectancy.

In order for me to change people's behaviors, I need to understand how they live and breathe; I need to understand how I live and breathe, in order to change my own behavior. And I can only do that by living with consumers, or at least spending substantial time with them. Now a lot of it comes down to understanding and decoding people's emotions, and based on that, trying to identify paths which can change people's behavior for the better. I don't need to tell you, I can change people's behavior for the worst as well. And I try to stay away from that as much as I possibly can. In some cases I would say I've fallen -- like one of the cases I give you in the book, about the [Allianz] life insurance commercial. It's not a really bad example, but still, I feel bad about [the fact that] I sort of persuaded them to use fear in their advertising.

Let's talk a little bit about privacy and data mining. I think many people who read "Brandwashed" will be startled to learn how often they give out information about themselves. But how many options do we, as consumers, really have? Sometimes -- just to give one example -- you can save a lot of money using in-store loyalty cards. Do the advantages of these things ever outweigh the disadvantages?

Well, if I had the time, as a consumer, I would try to do the following. First: Understand how deep your footprint is right now. The way you do that is by signing up to various services -- it's certainly easy in Europe -- which are specializing in basically scanning the Internet and understanding what information exists about you out there. They're not very expensive. And once you find those services, I can tell you one thing: You will be shocked by how much information is out there about you. You will be shocked, period. It will give you a wake-up call that you probably will never forget.

Now, once you then say to yourself, I want to trade off still, because I need whatever it is -- a company membership card I want to have, maybe -- then my best advice to you is that you do two things. One: You always have to read all the small print. And you will most likely discover through the small print that the [given] company will sell your information on to a third party. If they do that, do not go ahead. Because that's the best way for you to make your footprint become even bigger. ...

Secondly, I would say to myself, if I can avoid signing up to services which I know for a fact are earning their money not from me (because they are free) but from selling my information, in principle, I shouldn't use that service. Of course, it's easier said than done. But an example would be Gmail. Gmail is a great service -- unlimited space and whatever -- but here's the reality: Every word you type in Gmail will not only be used in order to customize ads around you, but also will be sold on in such ways that they can give advertisers a sense of how popular you are, as an individual, and therefore, if you affect another person, how strong an influence you have on that person in terms of recommending a brand. In my mind, that's pretty scary information. I would rather pay $9.95 to have my own Web account or email account, where I know they're not going to analyze what I'm writing about, and they're not going to sell the information on. You need to make these choices all the time. And if you can't [resist] -- you still want that membership card -- then do it. But I think you need to go through and tick all those boxes.

A major element toward the end of “Brandwashed” is your reality TV experiment with the Morgensons [a family that, at Lindstrom's request, moved to a community in southern California and recommended specific brands and items to their neighbors and friends]. This particular example is obviously extreme, but you suggest that similar ploys are not unheard of in real life. (For instance, you write that malls "often hire sexy, good-looking kids to stand casually in front of the entrance," tempting others to come inside.) How common is this phenomenon, really? Would I have come across this many times in my life?

I think there is a very good chance you would have, without being aware of it. I'm also pretty sure that after reading about the Morgensons, you will think about it. As you remember, I wrote about an instance where I came in contact with it myself, and did not even detect it -- it's a true story. So I think the reality here is that we are all to some degree affected by it. It may be extreme, like the cases I put forward; maybe it's more subtle -- you sit at a dinner somewhere, and someone next to you is talking very positively about something; they happen to be from that company, but you're not aware of it. Will it be bigger? Absolutely. There's no doubt about it.

Another question about the Morgensons: Did their friends and neighbors -- to whom they were continually recommending products of all kinds -- really not notice what was going on? They were recommending so many different things!

Yeah, they were -- so much so that even the producer thought it was too much. But no, [their friends did not notice anything], unless they lied to me. ... I spent considerable time with the primary groups of friends to interview them -- and we had a "Today" show psychologist with us, too; both of us are pretty good at listening and talking to people, and we didn't detect anything. I'm almost 99.9 percent sure that it was the truth we got out of it -- and if that is the case, first of all, I'm surprised, and second of all, I'm surprised that they were not angry! Legally, I was pretty sure I would be sued to death, right? But it was not the case -- touch wood.

Can you single out one ad campaign from the past few years that you thought was particularly good? Either an especially honest campaign, or maybe just one that you admired more than most?

[There's a Dove campaign that I think] still makes sense -- not using photo models, but using ordinary people to advertise for cosmetic products. It went viral. It was actually developed in Canada originally, that viral video where you see a person being transformed from looking ordinary to looking like a photo model. I think that campaign was and still is a great campaign. I do know for a fact it didn't work as well as Unilever was hoping, but I think in contrast to all the stuff we see out there, it's a great campaign because it's true to its products.

Again, let's be realistic. We cannot close down the gates of brands. If I said to you tomorrow, I'm sorry, you're not going to buy any cosmetic products at all -- end of story -- then I'm sure that you would be pretty angry. But why don't we try to create an industry which is more transparent? I'll tell you, I have been in those executive meetings with cosmetic companies ... In one meeting, I said to them (as a joke), "We should have more mystery built into our product" (this is some years ago). And the executive from the R&D department said, "Well, let's add some water." And it was very telling [given] what the view is of that industry -- selling hope in a jar. Of course, we know today the placebo effect has huge influence on how we think, and even the look we have; we know that from lots of studies conducted. But this is probably going too far. And I think that Dove actually managed to tread that fine line. So kudos to Dove on that one, yes.

My final question is about your personal brand. In the book, there's a good deal about you and your own successes; part of the whole selling point is your experience and expertise. Is it hard to put out a book about branding tricks without looking like you're trying to oversell your own brand?

It's a very, very fine balance. First of all, I need to ask myself: Is the product good? And secondly: Does the product harm anyone -- or does it help people? If I feel it can tick those two boxes (and I feel fairly comfortable about ticking those two boxes [in this case]), then I need people to read the thing. And as you know, you could end up with the operation succeeding but the patient dying -- meaning that it's a great book, but I'm not building my brand, so no one will read it. And I think that that's my fine balance here. Yes, I am branding myself hard, because that's in my nature, and I've done that for so many years now. If I've gone too far, tell me -- everyone. I really mean it. If I go too far, tell me. Because then I'm prepared to change. And sometimes you do become blind. But I think my excuse here (and it may be a bad excuse) is that if I don't get the ears of people, I won't get anywhere. So it's just a fine, fine balance.

Shares