Americans are angry about a political system that seems incapable of responding to the needs of ordinary people. Many people have found a new "ism" to denounce: "corporatism." Until recently, "corporatism" referred to government-sponsored cartels. This outlandish word was seldom to be found, except in denunciations by right-wingers of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal, which, they claimed in their sectarian ghetto literature, was a copy of Mussolini's Italian fascism. (Don't even ask, it's too silly to explain).

In the last few years, however, the term has broken loose from its moorings, and "corporatism" now seems to have become an elastic, pejorative phrase for any dealings between government and business of any kind, other than arm's-length regulation. A number of conflicting and not necessarily related things are lumped under the ever-more-inclusive term "corporatism"-- everything from public venture capital for emerging technologies to the outsourcing of government functions to for-profit contractors to political contributions by companies and lobbies. A word that once had a narrow and fixed meaning is in danger of becoming an empty, all-purpose insult, like the epithets of "fascism" and "socialism" hurled by conservatives at anyone who disagrees with them.

Unlike "fascism" and "socialism," however, "corporatism" is used as a catch-all denunciation by many on the left as well as the right. The right and left alike have recently found proverbial poster children to symbolize this sinister government-business "corporatism."

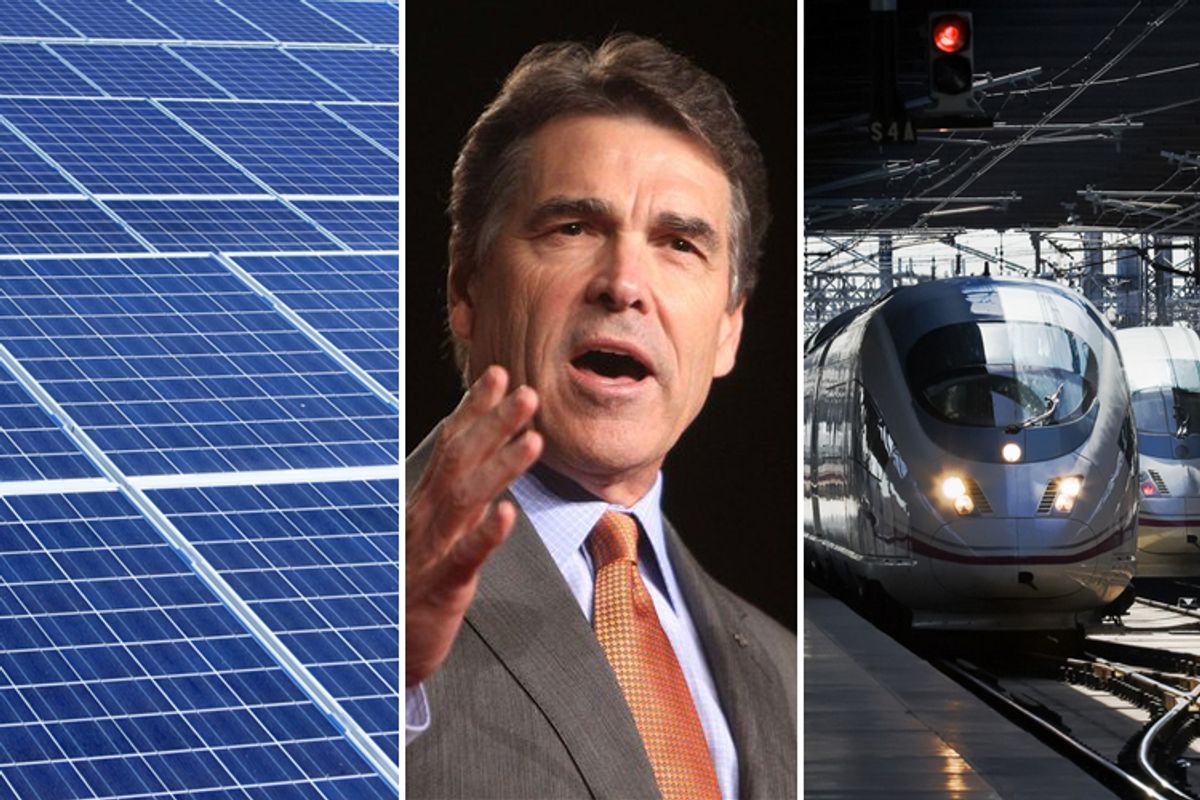

The right has Solyndra, the failed solar energy company that benefited from federal subsidies and the attention of the Obama White House. The left has attacked economic development agencies of Rick Perry's Texas government, including the Emerging Technologies Fund, which, according to news reports, disbursed much of its largess to interests that contributed to Gov. Perry among other politicians.

But there's a problem with over-the-top denunciations of government programs to foster particular sectors and technologies. Other countries routinely and often successfully promote their industries using a variety of "corporatist" measures including favorable access to credit, procurement, state-owned enterprises and tax incentives, to say nothing of techniques like China's currency manipulation and Japan's disguised barriers to imports. To give only one example, using government subsidies Japan, South Korea and China have raised their combined share of global commercial shipbuilding from less than 10 percent in the 1970s to more than 80 percent today.

Government sponsorship of targeted industries and technologies is not controversial in most of the world. On the contrary, it is the norm in advanced countries and developing countries alike. Utopian Marxists and equally Utopian libertarians may denounce industrial policy, but there is no reason for mainstream liberals or conservatives to object to these tried-and-true methods of economic development used by local and national governments.

That doesn't mean that every example of public sponsorship of private business is legitimate. Any political agency, like any human institution, can be perverted and suborned to serve the wrong purposes. The Emerging Technology Fund in Texas, for example, assigned final decisions about funding to the governor, lieutenant governor and speaker of the House. That is a model of how not to organize a public venture capital agency, if the goal is to insulate decision-making from political pressure.

But it is one thing to conclude that particular economic development programs have been turned into slush funds or campaign kitties, and another to accept the theory that any collaboration between business and government other than arm's-length regulation represents corruption that threatens to destroy capitalism (according to many on the right) or replace democracy with rule by corporations (according to some on the left).

To be sure, demonizing all collaboration between government and private enterprise as "corporatism" or "crony capitalism" provides an appealingly simple diagnosis of the nation's ills that can unite anti-government libertarians with anti-capitalist leftists and old-fashioned populists. It makes for sound bites and slogans. It resonates with the powerful Jeffersonian strain in American culture, which despises bigness -- big government, big business, big banking, big labor -- and treats politics as a melodrama pitting the unitary, easy-to-perceive "public interest" of the many against conspiracies by "special interests." Nobody ever lost an election by promising to protect the People against the Interests.

The fact remains that collaboration between public enterprise and private enterprise has contributed to America's success since the earliest years of the republic. In the 1790s, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson's rival Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton sought to jump-start American industrialization with a federally chartered private entity called the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures. While the initial effort failed, it catalyzed the growth of the important industrial town of Paterson, N.J., which had a major role in American industries from locomotives to the silk that gave Paterson its nickname, "Silk City."

Because capital was scarce in early America, many large-scale projects like canals and roads were undertaken by corporations that were owned in whole or in part by state governments. Between the 1850s and the 1870s, the federal government used land grants and other subsidies to promote the private construction of transcontinental railroads. The project was wasteful, corrupt -- and successful, reducing travel times from the East to the West Coast from months to days.

Libertarians often claim that one railroad baron, James Hill, built a transcontinental railroad, the Great Northern, without any government subsidies. The libertarians are liars. Hill and his partners inherited millions of acres of government land grants when they bought a failed railroad, the Saint Paul and Pacific. Franklin Roosevelt, in a speech at the Commonwealth Club of San Francisco, delivered a nuanced verdict on the railroad tycoons in a 1932 campaign speech at San Francisco's Commonwealth Club:

"The financiers who pushed the railroads to the Pacific were always ruthless, often wasteful, and frequently corrupt; but they did build railroads, and we have them today. It has been estimated that the American investor paid the American railway system more than three times over in the process; but despite this fact the net advantage was to the United States."

Government procurement has been as important as government subsidies. For more than two centuries, military procurement has nurtured one infant industry in America after another. Federal arsenals developed the "armory system" that spread to the private sector and evolved into mass production. Following the success of the Wright brothers, the federal government fostered American aviation with military and air-mail contracts, as well as technological research performed by a government agency called the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). Founded in 1915, NACA became the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in 1958.

Following World War II, President Woodrow Wilson was worried about excessive American reliance on British radio technology and networks. At his direction, a young assistant secretary of the Navy and future president named Franklin Delano Roosevelt directed the Navy to fund the creation of a public-private consortium called the Radio Corporation of America (RCA). At the government's request, GE, Westinghouse, ATT&T and other companies pooled their radio-related patents to ensure that interlocking American corporations controlled radio development in the United States.

During World War II and the Cold War, the federal government adopted a new strategy for promoting enterprise: large-scale funding of scientific and technological research. With federal funding, much of it military or health-related, researchers in universities and corporations split the atom, developed the jet engine, created a vaccine for polio, developed rocket and satellite technology, developed digital computing and the Internet and mapped the human genome. While much of the work was done by nonprofit research universities, large corporations like IBM and Boeing were responsible for a lot of the innovation and were well-remunerated for their contributions. If this be "corporatism," America needs more of it.

Today a government-backed private project of which you approve is enlightened "public policy," while one of which you disapprove is "corporatism" or "crony capitalism." We would be better off spending more time debating particular projects and policies on a case-by-case basis, and less time shadowboxing with amorphous "ism's," including "corporatism."

Michael Lind is policy director of the Economic Growth Program at the New America Foundation.

Shares