Like Touré, I get nostalgic for the monoculture. It certainly seems like an alluring idea. The monoculture reinforces the belief that what we as critics spend so much time thinking about really is a central part of the way our society lives and breathes. Otherwise it might be hard to believe in the primacy of pop music when millions of people are out of work and our government is crippled by deep systemic dysfunction. But the best thing (or the worst thing, if you’re writing a think piece) about the monoculture is that it exists safely in the past, where it can live on in our imaginations as a mythical place where, as Touré recently wrote in Salon, “an album becomes so ubiquitous it seems to blast through the windows, to chase you down until it’s impossible to ignore it” — an all-powerful communal unity that comments on the shortcomings of the present.

If I’m feeling really nostalgic, I’ll think about seeing the video for Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” on MTV for the first time, back when I was in eighth grade and eating at home alone on my lunch break in the fall of ’91. You know, the good old days — when I had to ride my bike an hour one way to the record store to buy a CD for $14.99 because I liked the one song I heard on my town’s only rock radio station. Ah, sweet inconvenience.

I’ll remember going back to my junior high school that afternoon and talking about the video with all of my classmates. We knew instantly that “Smells Like Teen Spirit” signaled the dawn of a new era in pop music; it expressed our joys and fears, and pointed the way to a new future. We pledged to commit all the details of this moment (sorry, Moment) to memory, so that when our children asked us what it was like When The World Changed Forever, we would be able to pass down the tale.

Oh, wait a second: It didn’t happen that way at all.

Yes, I saw “Smells Like Teen Spirit” video over lunch, but nobody seemed to know who Nirvana was when I got back to school. It wasn’t like my friends could just punch up the video on their iPhones after I told them about it; the clip was in heavy rotation on MTV, but you still had to watch the channel for an hour or two (and at certain times of the day) to see it. Once my classmates did see it, a number of them purchased "Nevermind," as I did. But many of them didn’t. Some preferred Pearl Jam. Some liked N.W.A.’s "Niggaz4life." Some didn’t care about music at all; they’d rather play Tecmo Bowl. Then there were the millions and millions of Americans who bought Garth Brooks’ "Ropin’ the Wind," the best-selling album of 1991. If anything, that was the album that we as a culture were united behind — it sold 14 million copies, though I never heard it once blasting through people’s windows.

You’d think that people living in a monoculture would be able to agree on a soundtrack for all the shared experiences we were having. But guess what: People have always had differing opinions and tastes, even when they had fewer media options. I’m not saying that the monoculture is a fantasy created by myopic critics who willfully misremember the past and project their personal experiences onto a diverse population ... actually, that’s exactly what I’m saying. Not only do monoculture fetishists romanticize a bygone era of centralized media that nobody really misses — three TV networks! Limited radio playlists! Art-house films that only play New York and L.A.! — they have constructed a utopian concept of cultural “togetherness” that only ever appeared to exist because of that very same centralized media.

Talking about the long-lost monoculture is a rigged game, because media used to be a relatively modest beast controlled by a select few gatekeepers. If you want evidence that “everybody” loved "Thriller," you can point to Billboard, Rolling Stone and MTV and not see any dissenting opinions — not because they weren’t there, but because those voices didn’t have access to media with any reach beyond a select cadre of in-the-know aesthetes. Dig a little deeper, though, and you’’ll find “Political Song for Michael Jackson to Sing,” a song that has nothing to do with Jackson other than the snarky title, from the Minutemen’s 1984 punk classic "Double Nickels on the Dime" — a record that, in certain circles, another kind of “everybody” likes.

I thought about the monoculture last week while surveying the media coverage of Steve Jobs’ death from pancreatic cancer. Much of the media veered into straight-up hagiography as it lionized the Apple CEO — grief over celebrity deaths remains our most potent form of monoculture — but there was a significant minority of publications and websites that sought to put the tragic early demise of a fabulously wealthy manufacturer of high-status tech products in a less deified perspective. In a different time, coverage of the Jobs story would have been monochromatic, handed down from daily newspapers and the television evening news; today, we’re afforded a broad range of commentary — some insightful, some maddening, all equally accessible.

We all know deep down that this is a good thing, right? The old media structure presented an oversimplified view of our world that people at the time rebelled against. (Hence the proliferation of “underground” culture standing in opposition to the mainstream. Today, all culture is aboveground.) Our monoculture was an illusion created by a flawed, closed-circuit system; even though we ought to know better, we’re still buying into that illusion, because we sometimes feel overwhelmed by our choices and lack of consensus. We think back to the things we used to love, and how it seemed that the whole world — or at least people we knew personally — loved the same thing. Maybe it wasn’t better then, but it seemed simpler, and for now that’s good enough.

But yearning for monoculture is like wishing that men still wore hats in public: Guys back in the ’50s might have looked handsome, but beneath that uniformly tidy facade were dudes who drank too much and didn’t respect women. Our world has always been a complex mass of contradictions; it’s just that we’ve finally turned on the lights and seen all the ants scatter.

What’s really incredible about monoculture nostalgia is thinking it ever applied to music. Anyone who has spent time in a high-school hallway knows that music is used to separate youth culture, not bring it together. More than any other popular art form, music is a vehicle for self-expression for the audience; there are so many genres, and sub-genres tucked inside genres, that picking your favorite is a way of choosing the kind of person you want to be, and (more important) who you don’t want to be. Punk, metal, rap, country — they all come with unique clothing styles, slang, postures and ideologies ideal for young people looking for different personalities to try on, or react against.

“Now the music divides us into tribes/ you choose your side, I’ll choose my side,” sings Win Butler of Arcade Fire on 2010’s “Suburban War,” a song about growing up outside of Houston in the early ’90s, the time right before the Internet came along and supposedly fragmented our blessed monoculture. But if great popular albums from the period like "Nevermind" and "The Chronic" were important at all, it’s that they showed a whole lot of people that there was really great music being made below the radar of the mainstream. The scenes those records came out of — the indie rock and rap music of the ’80s — didn’t get played on the radio; as a result, kids like me had no idea this music even existed until Nirvana and Dr. Dre showed up on MTV. When they did, I didn’t think, “Wow, it’s great that the masses finally get to hear this music.” I thought, “What in the hell else are they keeping from me?”

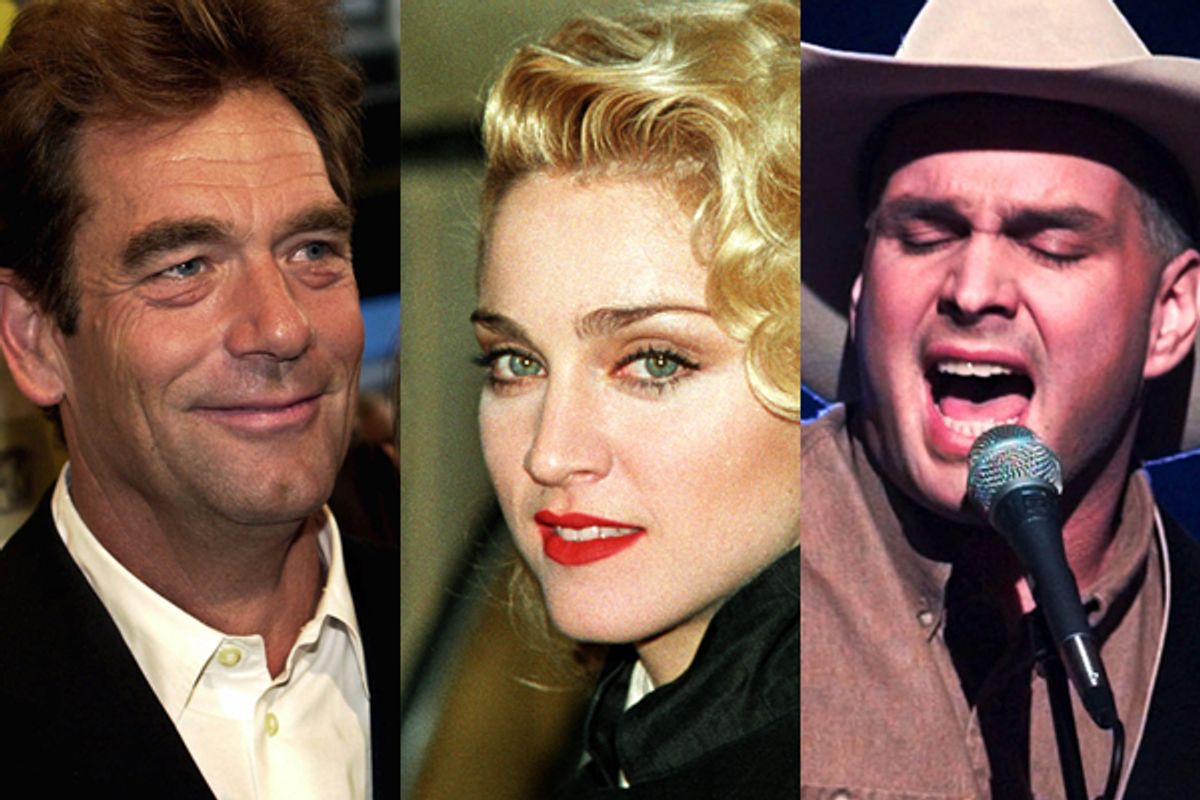

Instead of pining for a return of monoculture, how about speculating about the impact the Internet could have had on the careers of the Replacements and Eric B. & Rakim in the ’80s. Imagine if those artists had been as available to the average music fan as Madonna and Huey Lewis and the News. If given the choice, isn’t it possible that Madonna and Huey would have sold fewer records back then, while allowing for masterworks like "Let It Be" and "Paid in Full" to reach more people?

But albums sales (or just albums, period) don’t tell the whole story in this age of rampant downloads and music streaming services with exhaustive libraries. The world has changed, and so has our connection to music — though that doesn’t mean it has weakened. Musical popularity used to be measured by sheet-music sales, but just because people aren’t gathering around pianos for family singalongs doesn’t mean they don’t care about songs anymore.

If we stop looking to the past, we might realize that we’re living in a golden age of music listening and discussion. The Internet has enabled more people to hear more music than at any point in human history. More people are writing about music than ever — on websites, on personal blogs and Facebook pages. There are lots of niches out there, but unlike the music scenes of the past, people don’t live there exclusively; we’ve become a culture of song-sampling polymaths, slotting Drake next to Mastodon, Real Estate next to Robyn, and Jamey Johnson next to Beyonce in our iTunes playlists.

With minimum effort, you can find worthwhile music online, and thoughtful fans to talk about it with. Countless connections over shared passions for artists, albums and songs are being made among strangers every day. It’s all part of a conversation that is thriving, vital and thrillingly multi-cultural. Think about it: If you were living in a monoculture, don’t you think you’d want the world to be like this?

Steven Hyden is the music editor for the A.V. Club.

Shares