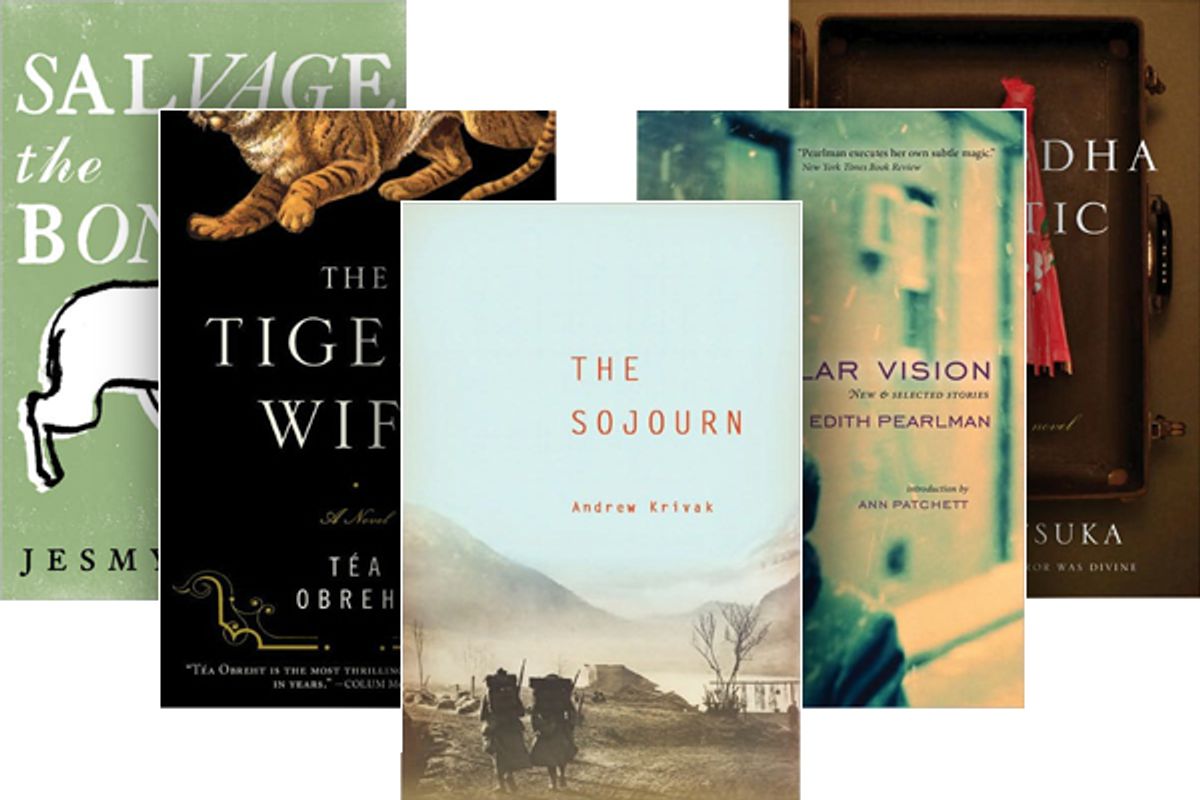

The short lists for the National Book Awards were announced in Portland, Ore., on Wednesday, with the annual ritual head-scratching following closely behind. As usual, it was the fiction list that provoked the most comment; it's an assortment of low-profile and/or small-press offerings, with the exception of Tea Obrecht's bestselling debut, "The Tiger's Wife."

Over the next day or two, expect to see observers pointing out the absence of two widely praised fall novels -- "The Art of Fielding" by Chad Harbach and "The Marriage Plot" by Jeffrey Eugenides -- and the fact that four of the five shortlisted titles are by women. (Those with longer memories will hearken back to the much-discussed all-female short list of 2004.) However, two prominent new novels by women, Ann Patchett's "State of Wonder" and Amy Waldman's "The Submission," were passed over, as well.

Although the judges for the NBAs change every year, the sense that the fiction jury is locked in a frustrating impasse with the press and the public is eternal. (One notable recent exception: the selection of Colum McCann's "Let the Great World Spin" as the winner two years ago.) The press, assuming that the amount of media coverage a novel gets is a reliable indicator of its merit, expresses bafflement. The judges, if they respond at all, defend their choices as simply the best books submitted.

Neither view is entirely persuasive. While it's certainly true that celebrated novels are not necessarily good, it's also true that they aren't necessarily bad, either. Whatever policy each panel of judges embraces, over the years, the impression has arisen that already-successful titles are automatically sidelined in favor of books that the judges feel deserve an extra boost of attention. The NBA for fiction often comes across as a Hail Mary pass on behalf of "writer's writers," authors respected within a small community of literary devotees but largely unknown outside.

It's understandable that the judges (all fiction writers themselves) want to correct this neglect, and that the press interprets this as a rebuke to its own judgment. However, the larger reading public has also proven recalcitrant. If you categorically rule out books that a lot of people like, you shouldn't be surprised when a lot of people don't like the books you end up with. This is especially common when the nominated books exhibit qualities -- a poetic prose style, elliptical or fragmented storytelling -- that either don't matter much to nonprofessional readers, or even put them off.

If outsiders fail to sympathize with the judges' perspective, the judges often have a distorted sense of the role literature plays in the lives of ordinary readers. People who can find time for only two or three new novels per year (if that) want to make sure that they're reading something significant. Chances are they barely notice media coverage of books -- certainly not enough to see some titles as "overexposed" -- and instead rely on personal recommendations, bookstore browsing and Amazon rankings.

Prizes are one part of this mix, if an influential one, and the public mostly wants the major awards to help them sort out the most important books of the year, not to point them toward overlooked gems with a specialized appeal. In a culture dominated by film and television, all literary novels are so obscure as to be virtually invisible, and books that seem ubiquitous to people embedded in the publishing world are anything but to those who aren't. (The next time you're waiting for a bus, ask the person next to you if he or she has heard of Jeffrey Eugenides or "The Art of Fielding." Hell, ask them if they've heard of Jonathan Franzen.)

For these reasons, the National Book Award in fiction, more than any other American literary prize, illustrates the ever-broadening cultural gap between the literary community and the reading public. The former believes that everyone reads as much as they do and that they still have the authority to shape readers' tastes, while the latter increasingly suspects that it's being served the literary equivalent of spinach. Like the Newbery Medal for children's literature, awarded by librarians, the NBA has come to indicate a book that somebody else thinks you ought to read, whether you like it or not.

As a kid, after several such medicinal reading experiences ("... And Now Miguel" by Joseph Krumgold was a particular chore to get through), I took to avoiding books with that gold Newbery badge stamped on their covers. If it weren't for a desperate lack of alternatives one afternoon, I'd never have resorted to E. L. Konigsburg's "From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler," which became one of my favorites. Today's adult readers, with millions of titles a mere click away, are unlikely to find themselves in such straits.

I don't doubt there have been similarly wonderful books scattered throughout the NBA's famously esoteric short lists over the years. (I can also attest that there's been more than one pretentious turkey.) Whether the NBA will hold onto its fading ability to get anyone to read them is another matter.

Shares