At one point during Tuesday night's GOP debate, Rick Santorum belittled Herman Cain's "9-9-9" tax plan, arguing that it would never pass Congress. This prompted a thunderous retort from Cain: "Therein lies the difference between me, the non-politician, and all of the politicians. They want to pass what they think they can get passed rather than what we need which is a bold solution. 9-9-9 is bold and the American people want a bold slution."

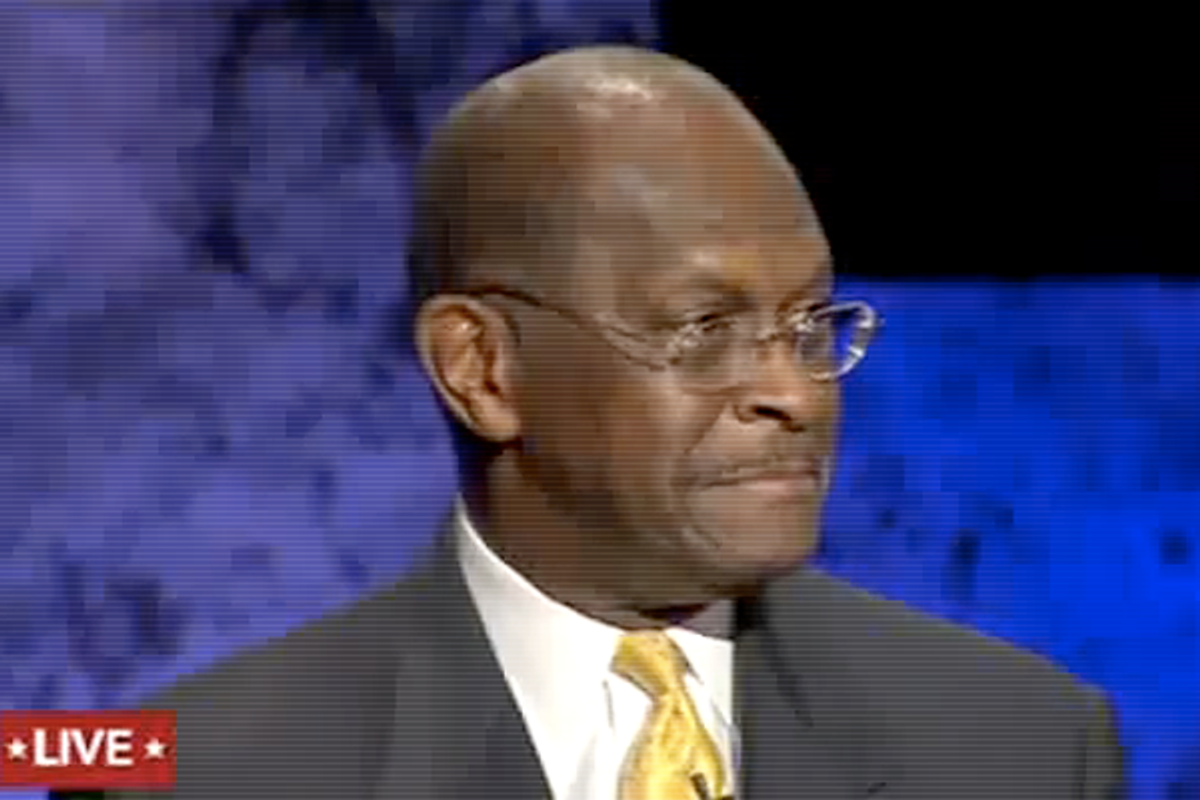

I'd say Cain got the better of Santorum in this exchange, partly because his delivery was so powerful but mainly because of the superficially compelling nature of what he was saying. 9-9-9 is a simple, catchy idea that surely does sound bold to the average viewer, especially since it's being pitched by a businessman who has no previous experience in elected office and who is being told by career politicians like Santorum that it's not practical. Cain's rise to first place in national polling (and in Iowa) certainly demonstrates how truly reluctant Republicans are to get behind Mitt Romney, but it's also the latest affirmation of the power a simple tax plan gimmick.

After all, we've seen this sort of thing play out before. On the Democratic side, there was the 1992 version of Jerry Brown, who jumped into the race shortly after ending a nearly decade-long exile from politics. The Brown of '92 pitched himself as a hell-raising outsider with contempt for the political establishment and corporate power. He offered a series of bold, maybe even radical policy prescriptions. The highlight: Junking the federal tax code and replacing it with a flat 13 percent income tax and a 13 percent value added tax. He seemed to introduce the idea almost on a whim during a debate early in the primary season, when he was struggling for attention, but as the field winnowed and front-runner Bill Clinton's negative ratings rose, Brown began breaking through. He turned the flat tax into a rallying cry, picking up copies of the tax code during speeches and throwing them into trash cans. Since he was positioning himself as a champion of the underclass, Brown made for a curious flat tax messenger, but the electorate's initial reaction was positive and Brown scored one of the biggest surprises of the modern primary era, winning Connecticut's late-March contest and setting up a two-week death match in New York with Clinton.

On the Republican side, there's the example of Steve Forbes, which I outlined a few days ago. The short version is that Forbes jumped into the 1996 Republican race late an with virtually no name recognition, but quickly distinguished himself by offering a 17 percent flat tax plan. (It helped that he could dip into his own pockets to pay for a barrage of ads promoting the plan.) Like Cain today, Forbes claimed that the derision of his rivals was symptomatic of their insiderdom -- and proof of how much his bold plan unnerved the establishment. Just a few weeks before the New Hampshire primary, Forbes made the cover of Newsweek (this meant something back then) and grabbed the lead in the first-in-the-nation state.

Of course, neither Brown nor Forbes went on to win, partly because their plans gave their opponents -- and the media -- endless ammunition. Clinton emphasized the regressive nature of Brown's flat tax, calling it a "rip-off" and noting that "I'd get a tax cut out of it and the people that really made the money in the '80s are going to get a killing out of it." Forbes' GOP foes, as hard as it might be to imagine today, framed his plan as a politically suicidal giveaway to the super-wealthy (it would have exempted investment income from taxation). The relentless scrutiny wore down each man's standing; Brown lost New York while Forbes won only two primaries (Arizona and Delaware). Maybe there's a lesson here for Cain, whose own 9-9-9 plan comes with more than its share of potential ammunition: A catchy tax plan gimmick is a great way to move to the top in polling, but it may not help you stay there.

Shares