Just over two years ago, an Atlanta writer named Blake Butler submitted a story to Cal Morgan’s short fiction website, Fifty-Two Stories. Morgan, the editorial director of Harper Perennial, was so taken with Butler’s voice — “I was awestruck by how brilliant, unusual and challenging it was,” he said recently — that he published the story that day. Morgan soon signed him to a two-book deal, and he was confident enough in his new find to arrange a marathon, four-night public reading of Butler’s 400-plus page novel “There Is No Year.”

Butler, 32, is young and talented; and as the editor of a popular website of his own, HTML Giant, he brings a well-established link to his readers. He’s prolific, and he writes books that manage to be both earnest and cool. And for a major publisher like Harper -- part of the HarperCollins family -- he’s inexpensive. Butler received just a $10,000 advance for his first novel with Perennial, he said in an interview, and $20,000 for his follow-up, out this month, "Nothing: A Portrait of Insomnia."

“The stuff I do, I never really considered it major-house stuff… so I was surprised that he was even in to it,” Butler said. Because of Perennial’s faith in his work, Butler said he “never even really considered anyone else.”

In a sense, Butler represents everything that Harper Perennial has tried to become since it started a rebranding effort in 2005, trying to find its niche in the unpredictable world of contemporary book publishing. Like Vintage Contemporaries did in the 1980s when it published a series of novels by Jay McInerney, Bret Easton Ellis and Tama Janowitz that captured the zeitgeist, Perennial, with its line of handsome, affordable paperback originals — many of which are penned by members of Butler’s generation — is trying to establish itself as the home of a new kind of literary smarts and style. It's almost a small press inside a much bigger one -- authors get paid less than they might even from another HarperCollins branch, but still benefit from the publicity and distribution muscle.

“Some of the books we’re doing are almost avant-garde, a lot of them are by young writers, and a lot of the promotional efforts we do are online or in innovative new ways,” Morgan said in a recent interview. “But it still is all coming from this very deep-rooted sense of the physical book as our little sacred item.”

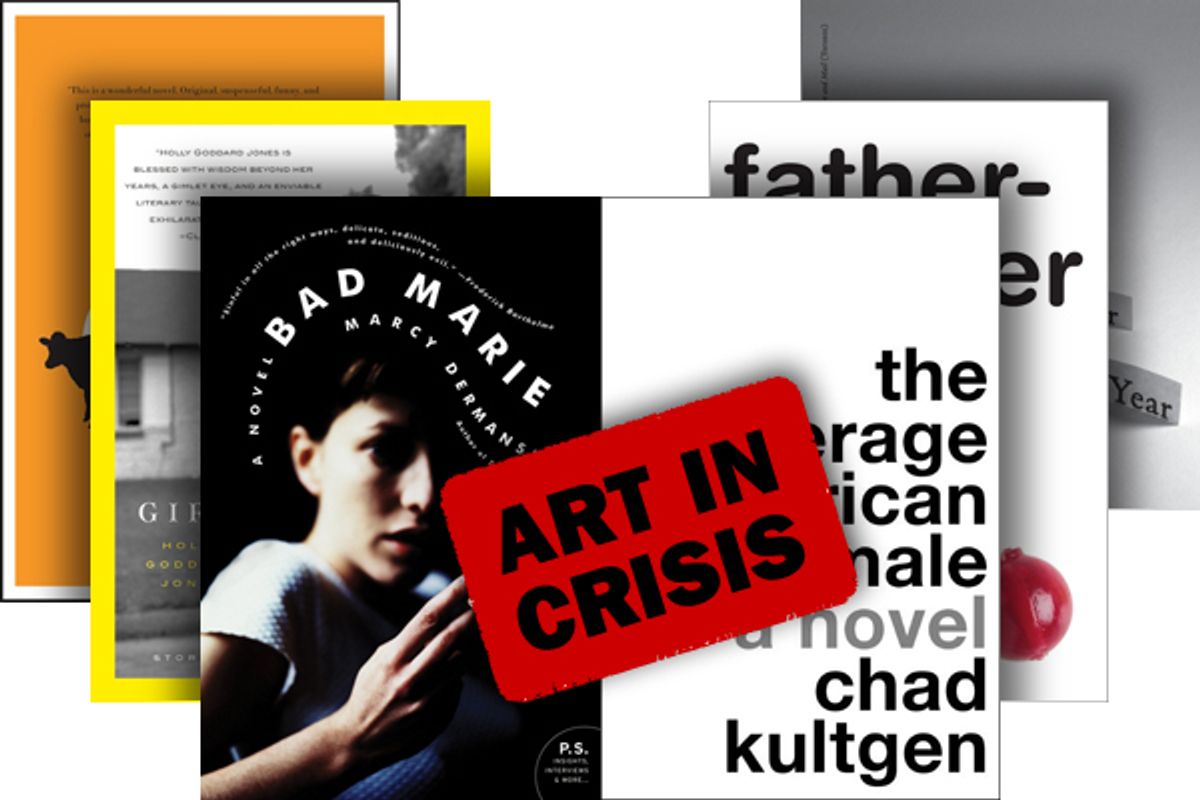

Harper Perennial’s model isn’t unique, but it’s an intriguing case study in what an imprint needs to do to distinguish itself in an increasingly stratified market. What it does is innovative and exciting, but also traditional. The imprint nurtures young writers, orchestrates creative — occasionally quite elaborate — marketing schemes, and packages its content in gorgeously designed paperback originals. There is no star system, no bidding wars, no big names — Perennial’s biggest author is not bonus baby Chad Harbach but the moderately well-known Chad Kultgen — and the imprint keeps its costs down by offering most writers modest advances for first novels and debut story collections. Nobody’s getting rich, yet the imprint fosters a sense of team spirit. In a series of interviews, more than one author described Harper Perennial as a “family.” In the best sense, Harper Perennial is selling a cutting-edge aesthetic on the cheap.

As Diana Spechler, the author of "Skinny" and "Who By Fire," and one of the many Harper Perennial fiction writers who’s in the early part of her career, put it in an e-mail interview, “Readers seem more willing to take a chance on a new or under-the-radar author if they don't have to spend hardcover prices.”

Perennial’s methods have caught the attention of some important people in the industry.

“They seem to be the one publisher that’s taking a lot more chances on new authors, for a major imprint,” said Gerry Donaghy, the new book purchasing supervisor at the mega-indie Powell’s Books in Portland, Ore. “There are a lot more quirky writers that sometimes you would expect to see on a much smaller press — somebody who maybe they’re only expecting to sell 2,500 or 5,000 copies of a book. And I think that’s where they’re sort of finding their niche, because they can certainly keep their doors open by cranking out copies of ‘To Kill a Mockingbird.’”

Kultgen, for one, was unknown when he came to Perennial. As he said in a phone interview this month, in 2006, “I had a book agent at the time who had sent it around to maybe like a dozen or so different publishers, who all said, 'This is hilarious, there’s no way we can publish it, though. Good luck.'”

After the round of rejections, a new agent representing Kultgen approached Perennial, where he found a home. “It’s kind of abrasive,” he said of his work, especially his first novel “The Average American Male,” “and I don’t necessarily think this, but I’ve heard this critique of it from a lot of people: that it’s highly misogynistic. I think for the most part the publishing industry may not want to do something like that, may not want to take a chance on it. But Harper Perennial certainly did.”

At 35, Kultgen has become one of Perennial’s reliable earners; in June the New York Times reported that his debut had sold more than 100,000 copies -- a figure that Morgan said was “accurate then.”

But sales figures like this are unusual for Perennial’s newer authors, who usually start small. “In an environment where we no longer have Borders as an outlet, we can start off by shipping fewer than 10,000 copies,” Morgan said.

For instance, “Bad Marie,” a 2010 novel by New York City writer Marcy Dermansky, had an initial print run of 10,000, she said in an e-mail interview. But the book, she added, “has been reprinted four times since then.” She said the continued interest in her novel is due in part to the imprint’s creative marketing ideas. “This August, Harper Perennial did an e-book promotion. Twenty books for $20. I loved that… Probably I did not make a lot on royalties with this promotion,” she said, “but I am happy that my book isn’t disappearing.”

An undeniable, if often overlooked, part of a publisher’s success is tied to the appearance of the books it publishes, and on this front few best Perennial. The imprint’s art staff, under Robin Bilardello and Milan Bozic, designs books that are pleasing to look at and equally gratifying in a tactile sense. “Reasons for and Advantages of Breathing,” a 2009 story collection by Lydia Peelle, is a good example: The sturdy, rough-hewn cover features an alluring black-and-white image of a solitary tree set against a cloudy sky, and unlike most paperbacks, it features wraparound flaps that give it a hardcover feel. With its playful reds pinks and yellows, Valerie Laken’s 2011 story collection, “Separate Kingdoms,” is no less attractive.

“I actually really love the cover art for the story collection,” Laken said, “and when they started to show me page proofs and they had all those great little graphics, I was thrilled. I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, somebody over there is really getting into this … We all like to think that stuff doesn’t matter, but of course you want to see your work presented in the most elegant and appropriate format.”

Morgan suggested that a book’s appearance might be more important than ever, given that different stores have varying visions, goals and layouts. “That means one thing for Barnes and Noble, it means a different thing for an independent bookstore, and it means a different thing still — and a very distinct thing — for a lot of the special markets that we sell into,” he said. “We’re really very focused on places like Anthropolgie and Urban Outfitters, places that do sell increasing numbers of our books every year. They look at our books as part of an extremely well-curated physical environment. If we have a book where we think the market is an Urban Outfitters consumer, we try to create a book that looks like it would make sense in their store.”

Harper Perennial publishes about “60 originals a year,” Morgan said, and the goal is to build a brand identity that transcends old-school and newer markets. Their authors include veteran underground writers like Dennis Cooper, smart young voices like Justin Taylor, new-breed Southern authors like Peelle and Holly Goddard Jones, and comic writers like Ben Greenman.

Some more traditional booksellers, however, suggest that it is hard to define a brand by being eclectic.

“Harper Perennial, it’s just been watered down to the degree that it no longer has its own identity,” Robert Contant, one of the owners of Manhattan’s St. Mark’s Bookshop, said recently. “I don’t know that there’s a certain kind of book that Harper Perennial is publishing anymore. There are some publishers — Europa (for one); they tend to be kind of small — that have a well-defined publishing list, and people will actually at least pick their books up and browse them just because of the imprint, but it’s not true for any of the major houses anymore.”

Whether or not this is true, one thing that seems beyond dispute is the loyalty that Harper Perennial breeds among its younger writers. Maybe that’s because the imprint gave many of them a shot when others publishers told them no. “It’s like a family,” said Simon von Booy, another young New York fiction writer who has published several books with Perennial. “It’s really a close-knit community. Everything people told me about publishing — they warned me away, they said be careful — I didn’t find any of that in my experience.”

Butler said he feels the same way.

“They’re such a tight-knit crew, and they’re all really good friends, and they make you feel like you’re part of that, too. I imagine it’s an anomaly in New York publishing,” he said. And he has no intention of going anywhere: “I have already got some other books that I’m finished with, and my full intention is to send them to Cal. I wouldn’t ask my agent to shop them at this point. If Harper wanted to do the book, then I would do it with them.”

Shares