Strange bedfellows don't get any stranger than this. To the joy of a few dozen graduate students and culture jammers, and the utter bemusement of just about everybody else, the most significant American protest movement in years has been spending time under the sheets with an obscure French avant-garde movement whose ideas are so crazily millenarian they make Jacques Derrida look like Mitt Romney.

I'm referring to the peculiar liaison between Occupy Wall Street and the Situationists – creators of one of those whacked-out intellectual commodities that have constituted France's most lucrative cultural exports for more than a century.

The link between Occupy Wall Street and the Situationists is the Vancouver-based anti-consumerist magazine and organization Adbusters, whose call to occupy Wall Street kicked off the now-global protests. In a recent interview, Adbusters co-founder and editor Kalle Lassn told Salon's Justin Elliott, "We are not just inspired by what happened in the Arab Spring recently, we are students of the Situationist movement."

This connection was odd enough that I decided to dust off my old copy of "The Society of the Spectacle" and see what, if any, help the Situationists might be able to offer the Occupy Wall Street movement. What I found would make those worthies spin rapidly enough in their graves to shake the Eiffel Tower.

I first heard of the Situationists in 1989, when I was doing research for a review of Greil Marcus' weird and wonderful book "Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the 20th Century," in which they play a leading role. They also popped up as one of the inspirations behind a zanily creative San Francisco-based group called the Cacophony Society, several of whose odd urban expeditions I took part in during the 1980s. Founding members of the Cacophony Society, in turn, helped create Burning Man, the most rockin' Saturnalia since Nero fiddled.

There is thus a strong connection between the Situationists and various counter-cultural carnivals, provocations and eruptions – a fact that holds both promise and peril for any political movement influenced by them.

That playfulness should be the most lasting legacy of the Situationists is ironic, for it's hard to imagine anything less playful than "The Society of the Spectacle," the 1967 book by Situationist founder Guy Debord that is the movement's bible. Grim, pedantic, hectoring and, not to put too fine a point on it, mad as a hatter, it is one of those works of Grand Theory that clank along like an ideological tank, crushing everything, including logic and common sense, in their path. Debord's theory is psychotically simple: "Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation." Yes, you heard right -- reality itself has been taken over, emptied out, by capitalist society, which has converted it into what Debord called "an immense accumulation of spectacles," mere images at which people can only gape like stupefied slaves.

Debord's bête noire is the commodity, which he regards as a demonic force that has literally taken over the world. "The fetishism of commodities generates its own moments of fervent exaltation," he writes. "All this is useful for only one purpose: producing habitual submission."

The Situationists did not talk much about an alternative world, an authentic universe outside the nightmare of the Spectacle. They aspired to create what one of their mentors, the radical French historian Henri Lefebvre, called "moments," and what they called "situations" (hence their name), that were radically new, that escaped the gravity of ordinary life.

Basically, Situationism is cultural Marxism on acid. It's an apocalyptic, hyper-theoretical variation on the Marxist theme that commodity capitalism has destroyed – or, in the jargon, "reified" – genuine human relations. Alas, like most Grand Theories, it looks better from a distance. "The Spectacle" is a concept so vast, malign and indefinable that it is essentially theological, like hell. And when Debord gets down to details, the contrast between the paltriness of his examples and the great and powerful Oz of the Spectacle can be positively ludicrous. "Trinkets such as key chains which come as free bonuses with the purchase of some luxury product, but which end up being traded back and forth as valued collectibles in their own right, reflect a mystical self-abandonment to commodity transcendence," he pronounces. "Those who collect the trinkets that have been manufactured for the sole purpose of being collected are accumulating commodity indulgences – glorious tokens of the commodity's real presence among the faithful. Reified people proudly display the proofs of their intimacy with the commodity."

Reified people of the world, unite! You have nothing to lose but your key chains!

It's a weird explosion of lucid paranoia. But the weirdest thing about the Situationists – and the one relevant to today's political scene -- was not their insidious, omnipresent enemy "the Spectacle," but the peculiar tactics they advocated to fight it. To overthrow the "pseudo-world" of the Spectacle, the Situationists proposed two "interventions." The first was so-called detournement, a fancy word denoting the practice of doctoring existing works of art, advertisements or publications so as to subvert their meaning. In practice, detournement is an erudite variant of painting a mustache on the Mona Lisa.

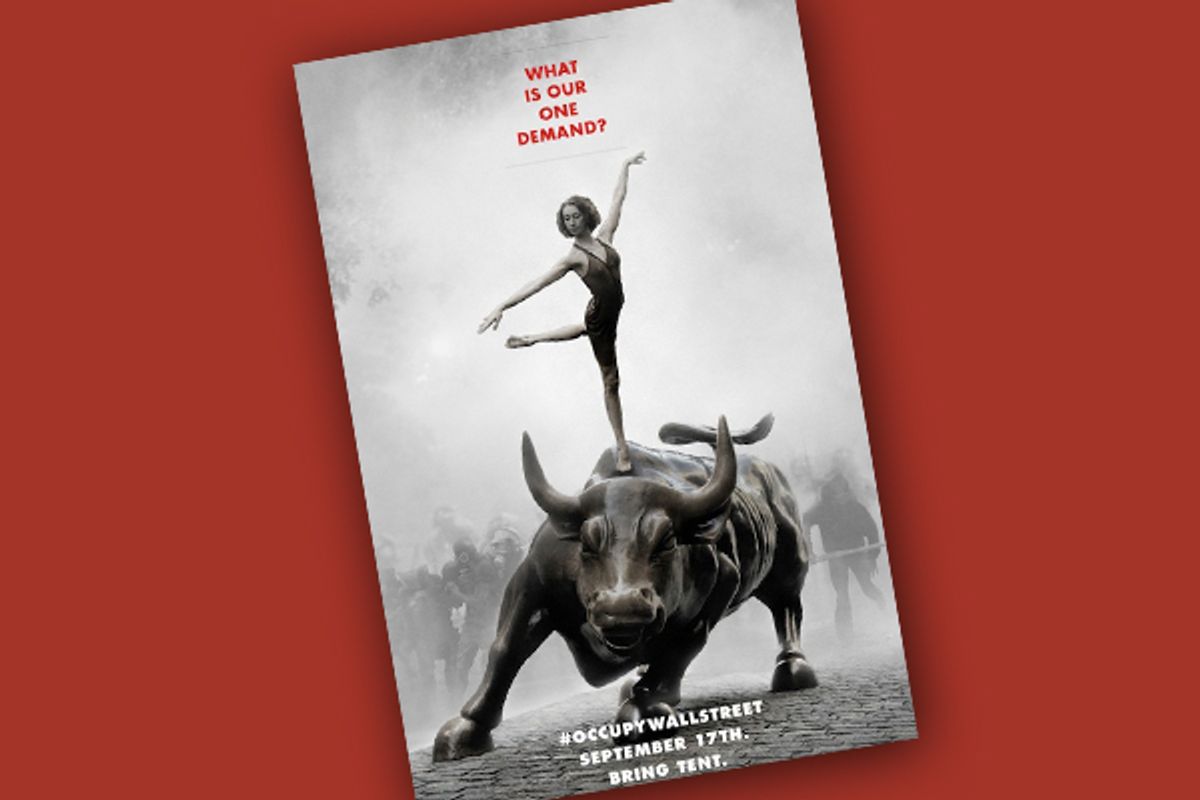

The now-famous Adbusters poster calling on people to occupy Wall Street is a subtle detournement. Ironically slick, it features a ballet dancer pirouetting atop a charging bull, which not coincidentally calls to mind the famous Merrill Lynch "Bullish on America" ad. (Presumably those Merrill Lynch executives who lost billions in collateralized debt obligations, then walked away with $3.6 billion in bonuses – a third of the now-defunct company's TARP bailout money – are even more bullish on America.) The ballet dancer is a pure Situationist icon: rather than being an allegory of earnest struggle, like a figure in a Stalinist boy-meets-tractor painting, she evades and exceeds politics.

The Situationists' second intervention was even odder. It consisted of the derive, a "creative drift" through the city in search of a lost "psychogeography" in which streets and neighborhoods, seen anew, would yield their dark and ecstatic secrets.

Call out the National Guard! The Situationists are drifting through the streets again!

By any real-world measure except for providing grist for countless future Ph.D. theses, the Situationists were a complete failure. They did have an outsize impact on the rhetoric – expressed on posters, publications and most famously in graffiti -- of the 1968 French protests that almost toppled Charles de Gaulle's Fifth Republic. "Never work," "Boredom is counterrevolutionary," "Under the paving stones, the beach" – these and dozens of other provocatively poetic pronouncements were written by or inspired by the Situationists. But their claim to have been the driving force behind the student revolt was overblown (Lefebvre flatly denied it), and Situationism itself as a movement barely outlasted those delirious days in May. The group never had more than 70 members, and Debord's tyrannical insistence on ideological purity meant that he was constantly purging fellow Situationists until by the end it was pretty much a party of one.

By refusing to bring their ideas down into the real world – it's hard to see how they could, since they considered the "real world" to be an empty fraud – the Situationists ensured that their influence would remain purely intellectual, not tangible. They paid lip service to the proletariat but had no knowledge of or interest in actual workers, and were unwilling to engage in the nitty-gritty work of organizing. At the end of "The Society of the Spectacle," Debord writes, "By rushing into sordid reformist compromises or pseudo-revolutionary collective actions, those driven by an abstract desire for immediate effectiveness are in reality obeying the ruling laws of thought, adopting a perspective that can see nothing but the latest news ... A critique seeking to go beyond the spectacle must know how to wait."

Despite the portentous italics (a favorite Debord device to create a sense of dramatic pseudo-profundity), this statement comes across as the temporizing of a mandarin. Just what we are supposed to wait for, and for how long, is never made clear: Presumably, we should still be waiting for Debord to give the all-clear. Because they remained snootily above the fray, the Situationists ended up as a cultural hood ornament, another flashy appendage of the "society of the spectacle" they were at such pains to decry. (The fact that they knew this would happen – they were constantly wringing their hands over the fact that commodity capitalism "recuperates" into itself all attempts to escape it – does not let them off the hook. Quite the contrary.)

It would seem the last place progressives should look for ways to build an effective movement would be a tiny, extinct priesthood of jargon-spouting frogs. As Ben Davis argued in a recent piece in ArtInfo," offering the Situationist playbook as an alternative guide for political engagement today would be like offering alcohol as a substitute for mother's milk."

When Adbusters did try to create an explicitly Situationist movement, it flopped. In November 2010, the magazine called for a "Carnivalesque Rebellion." "From November 22nd to the 28th, culture jammers of all kinds – from artists to churchgoers, anarchists to carpenters – will disregard the illegitimate laws of consumer society. For seven nights, they will honor instead the dictates of their hearts and the demands of their conscience. Overwhelmed by a myriad of insurrections and unexpected acts of resistance, consumer capitalism will grind to a halt," the manifesto incorrectly predicted. Its conclusion: "The Carnivalesque Rebellion is, above all else, a chance to rise above cynicism, skepticism, and ironic detachment. It is an invitation to don the prankster's mask, to regain the sense of magical possibility, and to finally start living." If he took a bunch of Prozac, Guy Debord could have written those words himself. And the number of people who turned out in clown costumes to bring consumer capitalism to a grinding halt was probably similar to the number of his acolytes.

But if the Situationists' ideology offers no guidance to the Occupy Wall Street movement, they still have something to offer it. Their ideas are good: The problem was that they elevated them into crackpot dogmas, suitable only for medieval scholastic disputations of the how-many-Spectacles-can-dance-on-the-head-of-a-pseudo-event variety. One does the Situationists no favors by taking their ravings literally. Strip away the crazy-Marxist, quasi-religious claim that under capitalism "spectacle" has completely replaced reality (an elementary category violation, in which a subjective feeling of alienation or grievance is elevated into a foundational principle – see "Tea Party" for an example on a heroic scale, with "government" replacing "spectacle"), and what is left is a smaller, but legitimate, insight about the insidious power of media to shape consciousness in the modern age. The Situationists' obsession with subverting pop media is evidence that they unconsciously recognized this. In similar fashion, strip away their hyperbolic rhetoric about how escaping the "spectacle" creates a totally new life and what is left is a smaller, but legitimate, insight into the liberating quality of rebellion – the carnivalesque (yes) fun of breaking out of habitual life. Both insights have inspired contemporary movements like culture jammers, and contemporary mass-controlled deliriums like Burning Man.

At bottom, despite their icy rhetoric, Frankfurt-School-Marxist-tinged pretensions to objective analysis and Young Turk-like aversion to sentimentality, the Situationists were romantics. Like a super-brainy, sex-starved Dante wandering through the Left Bank, they simply made the object of their desire impossible to obtain. Their ideology reflected the French mania for theory, but it also reflected the intoxicating spirit of the times. As the historian Walter Laqueur pointed out, "the European revolutionary movement of the sixties was, as in America, basically motivated by cultural discontent ... It was romantic in inspiration, and romantic movements are always based on a mood rather than a program."

So what can the Situationists offer today's progressive movement? First, it's pretty obvious what they can't offer. Mere cultural pranksterism is not enough: In fact, it's an insult. Today America – and the world -- is facing more serious issues than cultural discontent. Income inequality has reached grotesque levels: The 400 richest Americans own more wealth than the bottom 150 million, half the entire population of the country. Millions of people are out of work, healthcare is a disgrace, and the corrupt American financial and political system is incapable of responding. A nascent popular movement has sprung up in protest, but to be effective it must grow exponentially. On Oct. 15, when hundreds of thousands of protesters turned out in cities across Europe, an estimated 100,000 turned out in America – a decent showing, but not enough to shake the system. In particular, the movement needs to reach beyond its base, which is currently – at least in San Francisco, which may not be a fair sample -- made up overwhelmingly of the young and culturally disgruntled, those who have not even been able to get a foot in the American door. When I went down to the protesters' camp in Justin Herman Plaza this week, I talked to several highly intelligent young people with articulate grievances (including one recent college graduate who cited Erich Fromm's "Escape From Freedom," a book referenced by Debord) but there was nary a middle-class-looking person to be seen. This is not a judgment, and the vanguard of a movement are never the mainstream. But it is going to be extremely difficult for Occupy Wall Street to be effective unless this changes.

It's all about advertising. And this is where the Situationists come in – the most unwilling creative team in history.

The Situationists were the original Mad Men (in both senses of "mad.") Yes, they felt about advertising the way the Spanish Inquisition -- whose management style they appear to have emulated -- felt about heretics. But they hated it so much that they became experts in it. Their demented worldview, in which we're all trapped forever inside a gigantic Reality Commercial, led them to devise escape routes that utilized some of modern advertising's favorite techniques -- irony, collage and pastiche. Moreover, their interventions exuded a silly lightheartedness that, if used right, can move product.

Proof of the Situationists' ad acumen is that their successors have followed in their talented footsteps. According to Naomi Klein in "No Logo," several large corporations tried to hire AdBusters to create ironically hip ads for them.

So we're giving the Occupy Wall Street account to the firm of Debord and Debord. You got a problem with that, Campbell?

Debord and Debord will have to bring their A-game. OWS is a tough account, for reasons that were summed up succinctly by Mad Man and proto-Situationist nonentity Don Draper. "Advertising is based on one thing, happiness. And you know want happiness is? Happiness is the smell of a new car. It's freedom from fear. It's a billboard on the side of the road that screams reassurance that whatever you are doing is OK. You are OK."

The problem is that the people OWS is trying to sell to are not OK – and that fact has to be part of the pitch. How do you sell unhappiness? Making things worse, you're selling an act of individual rebellion – and Americans don't rebel. It's a comfort issue. How do you break through the inertia, fear of embarrassment, isolation and aversion to doing anything different that surrounds most middle-class Americans like a moat?

As the failure of the Carnivalesque Rebellion campaign shows, traditional Situationist techniques won't cut it. But as the ballerina-on-the-bull poster shows, the zany Situationist spirit can be effectively used. As Don Draper said, it's all about happiness. To get Middle Americans out of their armchairs and onto the street, the OWS campaign will have to do a tricky two-step. It will have to acknowledge that its viewers are unhappy, and use that as a motivation to buy the product -- but also convince them that they will be happier in the end when they do.

It's a tough sell, but Debord and Debord are pros. And ironically, a form of mass media far more omnipresent, inescapable, and all-devouring than the Situationists' worst nightmare may be their best friend. One shudders to think what the Situationists would have made of the Internet. And yet the Internet is what allowed the Occupy Wall Street movement to go global on Oct. 15. The Internet has allowed all kinds of information –mediated and unmediated, official and subversive and everything in between – to be instantly disseminated around the world. In Situationist terms, it is at once the Spectacle and its detournement. And most important, the Internet has expanded people's comfort zones. As familiar and unthreatening as television, a two-way form of communication that is now so internalized it functions like an extension of the individual, the Internet has changed the rules of the game. At least to some degree, it can help erode passivity. The success of MoveOn in raising millions of dollars for progressive candidates, on the left side of the political spectrum, and the rise of the Tea Party on the right, is evidence of this.

The big question, of course, is whether a movement can use the Internet to build communities beyond self-selecting ones. So far, no one has been particularly successful at this. But we are in a crisis, and things change during crises. Social media (although used disproportionately by young people) could play a role. One can imagine all sorts of creative ways of trying to mobilize middle-class people. Debord, who wrote that the family "remains repressive and offers nothing but pseudo-gratifications," would not sign off on this idea, but a "Take Your Mom to Protest Day" aimed at America's millions of unemployed college graduates would be a good start.

But for the campaign to really be effective, it will need to go beyond wit and playfulness. It will need to reflect the sense of solidarity and agency, rising at times to euphoria, that suffused the crowd at the Occupy San Francisco protest I attended. It will need to capture that rare, heart-lifting quality, one I witnessed on so many faces moving down Market Street: hope.

The Situationists were masters of carnival – but carnival is free. The happiness of people who have come together to work to change the world is something that has been paid for -- and it is precisely the price they have paid that constitutes their happiness. The language for this happiness is beyond the Situationists. To find it, we must turn to another, much greater, French philosopher.

In "The Rebel," Albert Camus wrote, "Awareness, no matter how confused it may be, develops from every act of rebellion: the sudden, dazzling perception that there is something in man with which he can identify himself, if only for a moment ... What was at first the man's obstinate resistance now becomes the whole man, who is identified with and summed up in this resistance. The part of himself that he wanted to be respected he proceeds to place above everything else and proclaims it preferable to everything, even to life itself ... [Rebellion] lures the individual from his solitude. It founds its first value on the whole human race. I rebel – therefore we exist."

Even a pitch as eloquent as Camus' probably won't get Americans to hit the streets. The economic-political-media system is deeply entrenched, Americans are notoriously passive, and the civic culture that encourages entering the agora to speak one's mind has withered. The odds are stacked against the Occupy Wall Street movement, no matter what it does. But it's worth a shot. The alternative is a future world even grimmer than that imagined by the Situationists.

Shares