The first thing she said was no. Then she began to scream. It went on for nearly a minute, loud and shrill, echoing down the quiet block of 16th Street in Brooklyn, N.Y., at 11:30 one night last March.

Across the street, Donald Harrington peered out his window. Down the block, Gretchen Barton called 911. A neighbor named Ray lumbered down his steps and rumbled, “Hey, what’s going on?”

The man loosened his grip on the woman. She sprinted up the block screaming. He ran too. Patrol cars arrived. They sped around the block to look for the woman and the assailant, but found neither.

When the police returned, Ray said he had a video that captured part of the attack.

“They said they didn’t want to see it because they didn’t have a complaining witness,” Ray, who did not want to give a last name, told the Crime Report. “Then they drove off.”

The incident shook the residents of the block in Park Slope, a brownstone-lined area in south Brooklyn. A month after the screams, they had heard nothing from the police. The neighbors did the only thing they could think to. They called the New York Daily News.

The video of that attack, captured by a camera outside of one neighbor’s house, went viral. It became one of what police came to call a “geographical pattern” of assaults in south Brooklyn.

By mid-October, the number had reached 20. One was a rape. Others were filed as attempted rapes, sexual assaults and gropings.

For weeks, residents, police and the press believed one of New York City’s most coveted neighborhoods had a serial rapist on the loose. The unraveling of that narrative illustrates our persistent misunderstandings about the nature, and prevalence, of sexual assault.

Truth In Numbers

The National Crime Victimization Survey estimates 188,400 people were raped or sexually assaulted in 2010. Yet thousands of these crimes go unreported to police. The survey shows only half of rapes and sexual assaults were reported to police. Even fewer made the news.

The stories that do appear in the press shape our understanding of sex crimes. At best, they empower victims to report, and the public to hold law enforcement to account. At worst, they serve to monger fear and convict the innocent.

The most salient example of the latter may be the 1989 rape of the Central Park Jogger, recently revisited by the Crime Report. Calls by the press and public to hang the “wolf pack” that allegedly raped the attractive 28-year-old investment banker encouraged the false conviction of five young men of color.

In 2002, a man serving a life sentence confessed to the crime. DNA evidence confirmed his guilt.

The case spoke to the public anxiety about the crime that plagued the city. Then the New York “Miracle” brought a precipitous drop in crime that outstripped even the steep fall seen around the country. Murder in New York has fallen nearly 75 percent since 1993, according to the NYPD’s CompStat data. Rapes have dropped by half.

Numbers, however, can lie.

Investigations by newspapers in Philadelphia, Baltimore, New Orleans and elsewhere have revealed elaborate schemes by police to make rape and sexual assault disappear. Some departments “downgraded” reported felonies to misdemeanors or non-criminal complaints. Others questioned the account of the victim or lost files in bureaucratic limbo.

A year after the Baltimore Sun revealed that police had deemed hundreds of potentially legitimate sexual assaults “unfounded” to keep numbers down, reported rapes have risen by 50 percent.

"More people are coming forward and reporting,” Sheryl Goldstein, director of the Baltimore Mayor's Office on Criminal Justice, told the told the Sun in July, “and those reports are being taken and handled appropriately.”

David R. Thomas, a law enforcement instructor at Johns Hopkins University’s Public Safety Executive Leadership Program, is a part of an effort to change the culture of policing around sex crimes.

“When we’re talking about sexual assault, when we’re talking about rape, the only other worse crime is murder,” Thomas said. “Look at the way we investigate this crime -- it’s just appalling.”

His training deals with all facets of the investigation, and focuses in particular on teaching law enforcement to treat people who report assault as victims rather than suspects.

“Training has to address the attitude that we walk in there with, because it totally impacts not only the victim sitting there before us, but other individuals that may be victimized in the future,” Thomas said.

Neighbors React

The officers’ attitudes after the March attack never sat well with neighbors in Park Slope.

Though clearly an assault, “they tried to say it was a girlfriend and boyfriend fighting,” neighbor Joe Barton told the Crime Report in June.

His wife, Gretchen, who had phoned 911, said the police “weren’t interested; not at all.”

“They just drove off without looking at the tape,” she added.

Law enforcement sources told the New York Post that the responding officers later told a 911 dispatcher that the complaint had been “unfounded.”

A few hours later, the victim phoned police. The report on her assault notes the existence of a surveillance video, sources said, but the police who interviewed her never went looking for it. Instead, her case was closed.

When the woman called back 10 days later to ask about the investigation, police apparently realized they had improperly closed the case. But Ray said that only after the video ran in the Daily News several weeks later did the Special Victims Unit ask to see the footage from his camera.

Gretchen Barton said investigators from the NYPD Internal Affairs Bureau told her in May they were looking into the case. “Something’s clearly not right,” she said.

As news of the attacks mounted, the wider community felt the same.

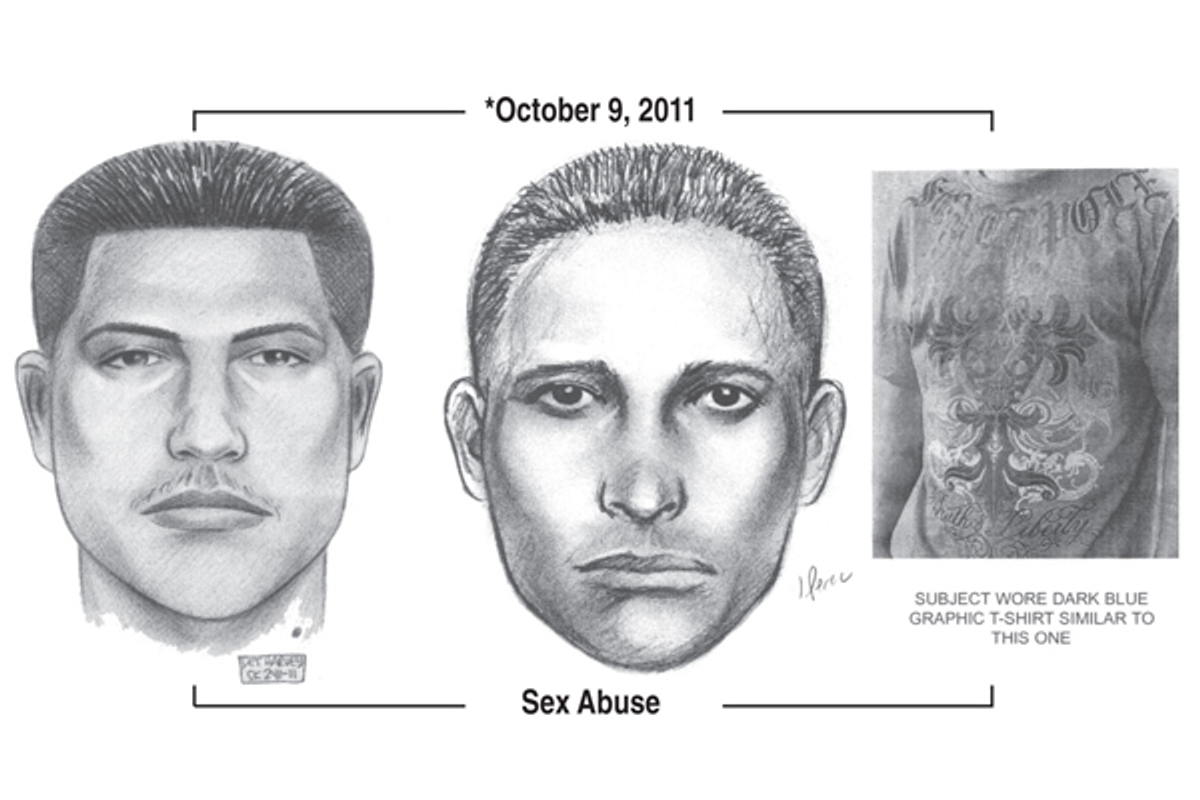

For weeks, news outlets and blogs reported on the Rapist, the Groper, the Monster, the Perv terrorizing the women of south Brooklyn. Police sketches posted throughout the neighborhood showed an array of generically Hispanic men in their 20s and 30s, described as short and wearing dark clothing.

Cyclists and walkers offered to escort women home from the subway. Locals organized a march to “take back our streets.” Feeling the pressure, police stepped up their presence. In the most affluent areas, they stood on every other corner.

Then on the evening of Oct. 11, the 72nd Precinct, where the majority of the incidents had taken place, held its monthly meeting. Cameras zoomed in on Precinct Commander Jesus Raul Pintos. In the last month, he said, four more women had been attacked. But the NYPD’s theory had changed.

“We’re not talking about a serial groper,” Pintos said. “It’s not some organized thing where there’s one guy.” How many “guys” might be going around, Pintos could not say.

A Hidden “Epidemic”

Even after the NYPD had given up the idea of a single attacker, the press and residents still talked about “catching the perp.” There was comfort there. To think of this as one man, or even a few, who terrorize the neighborhood made the threat tangible, but it also made it finite.

The truth about the Brooklyn attacks seemed more complicated. Asked if the spate of attacks could be gang-related, or the work of copycats, Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly said, “There may be some copycats. There also may be increased awareness of this and perhaps better reporting.”

Experts agreed.

“The problem of sexual harassment and groping in public spaces is epidemic,” said Suzanne Goldberg, director of Columbia University’s Center for Gender and Sexuality Law. “I think most women do not report women being groped on the street or in public transportation.”

“A value of increased media coverage is to empower women to report these incidents,” Goldberg explained. “The more reporting, the more chance that perpetrators will be caught, and that law enforcement will take more action.” Even so, she said, “It is very difficult for police to find the perpetrator and prosecute.”

By national standards, New York investigators appear to be doing better than most.

Experts believe about 400,000 rape kits sit untested nationwide, with dire consequences, as the Crime Report has explored. New York City, however, has tested every one since 2003. Officials believe this has led to an arrest rate of more than 70 percent.

Yet taking cases to court poses challenges. Research from the National Institute of Justice has shown that prosecutors can shy away from cases in which the victim has a previous sexual relationship with the perpetrator, cases that lack physical evidence, or instances in which the victim has been drinking.

Two of New York’s biggest news stories of the summer showed how bumpy the process can be.

In May, two police officers charged with raping a young, drunk woman in her home were acquitted of those charges. After the trial, Juror No. 8 published a 60-page account explaining how the 12 arrived at the verdict, which shocked much of the city. “We all felt they were guilty, but couldn’t prove it,” Patrick Kirkland, the juror, told CBS News.

The second is the case of Dominique Strauss-Kahn, former head of the International Monetary Fund. In May, a hotel maid accused him of forcing her to perform oral sex in his suite at the Sofitel Hotel.

The case began to unravel after prosecutors said the maid, for whom the traditional anonymity given to rape victims soon vanished, had lied throughout her accounts. The Manhattan district attorney decided the story told by Nafissatou Diallo, a 32-year-old immigrant from Guinea, was too tenuous for trial. In August, a judge dismissed the case.

Dismissals in assault cases are commonplace. In New York City, 2,629 felony and misdemeanor sexual assault cases went through the courts in 2010, according to the state Division of Criminal Justice Services. Less than 56 percent resulted in a conviction. More than 40 percent of cases were dismissed or not pursued by prosecutors.

The “Perp” Walks

In Brooklyn, police have struggled to build a strong case in the string of assaults. Three men have been arrested in connection with the 20 attacks. Charges were dismissed against the first man after police decided they had collared the wrong guy. A second walked free after a victim, who had originally picked him out of a lineup, recanted her identification. She said she just could not be sure.

If national statistics hold, thousands of assaults remain unreported in New York.

“The public just doesn't have an accurate assessment of the prevalence of crime in their communities,” said Carol Tracy, executive director of the Woman’s Law Project, who has been working to get widespread changes in the classification and investigation of sex crimes.

The narrative of the Brooklyn Groper has opened Brooklyn’s eyes to the prevalence of sex crimes.

But a yawning gap persists between the way we talk about sexual assault, and how it plays out in our communities.

As the tally of gropings climbed, certain numbers did not appear in the press. As of Oct. 16, 174 rapes were reported in Brooklyn South, the patrol borough made up of 13 precincts in the area. That number is up more than 58 percent since 2009. NYPD did not respond to requests to specify how many reported rapes were committed by strangers, or how it was addressing the increase.

The 72nd Precinct, where much of this story takes place, has 19 rapes on the books for 2011 -- a 90 percent increase over two years ago. To date, only one of those rapes has been tied to the assaults that have held the borough, and the press, in thrall.

Shares