Matt: Is there any other critic, dead or alive, who’s as ubiquitous as Pauline Kael?

Andrew: Absolutely not. As we’ll see, I have very mixed feelings about Kael and her legacy, but no other film critic has ever been remotely as popular or as influential. (One could argue that less famous writers like James Agee or Manny Farber are more “important,” in some sense, but that’s a different matter.) Kael’s influence is so pervasive it’s almost unconscious. When I was a younger critic and someone accused me of writing like Kael, I was enraged and responded that I’d never read her, which was almost literally true. When I did read her, I had to admit the guy had a point: I had absorbed some elements of her style and outlook without realizing it, as if through osmosis, because they were so ubiquitous in film criticism.

Matt: I’ve actually struggled with this myself. That prose style is so engaging — so powerful and seductive in some ways because it’s like a heightened version of everyday conversation with a really smart person — that it does sink into your mind, whether you’re a regular filmgoer of somebody who writes criticism for a living. Anybody who’s so inclined can actually track my own shifting feelings about Kael’s influence by looking at my past writing about her. I reviewed her 1994 compilation “For Keeps” for the Dallas Observer, my first employer, and it was pretty much a mash note. Seven years later, I wrote an obituary for her that was a lot tougher — respectful, ultimately, but skeptical of some of the very qualities I praised a few years earlier. This was probably because by that point I’d been living in New York for six years, a much richer moviegoing town with a lot more varied types of film criticism available in print, and I started to figure out that even though Kael was the most prominent and maybe influential voice in criticism, there was more than one way to write about movies. And television. And everything!

Andrew: Let’s talk about some of the distinctive and (perhaps) problematic qualities in Kael’s writing. As you say, her voice is both powerful and seductive. She worked very hard to discover and refine a style that was highly intelligent but also sounded very direct and American, and was not full of $50 academic words and intellectual pretension. And she was very clear about the fact that a critic’s role is to speak truth (as she sees it) to power, to be an oppositional cultural force, never to congratulate the powerful for being on top or the comfortable for having such good taste. I have some misgivings about the direction Kael went with that, ultimately, but it’s an important lesson, and one that too many people in our so-called profession ignore.

Matt: One of Kael’s finest qualities was that independent voice — independent not just of the normally parasitic relationship between print publications and the studios that advertise in them, but independent of the New Yorker itself, which until Kael came along, did not regularly publish prose as loose and lively as hers. Right now I’m rereading her 1983 review of “The Right Stuff,” which as much as I love that film, really nails Philip Kaufman’s odd mix of counterculture satire and very conventional, even square hero-worship. It’s got one of my favorite closing paragraphs: “If having ‘the right stuff’ is set up as the society’s highest standard, and if a person proves that he has it by his eagerness to be locked in a can and shot into space, the only thing that distinguishes human heroes from chimps is that the heroes volunteer for the job. And if they volunteer, as they do in this film, out of personal ambition and for profit, are they different from the chimp who might jump into the can eagerly, too, if he saw a really big banana there?”

Andrew: That’s fascinating, funny and perverse writing. It makes you laugh and offers a take on that movie that no one else would ever have thought of. A wonderful example. It’s also a good example — do I dare to say this? — of what I will suggest are Kael’s intellectual limitations. Of course there is a difference between a chimp and a human in the example she provides! The human goes into space knowing he is going into space, in pursuit of some grand, abstract vision, the idea of going to the moon or whatever, along with all the personal glory and fame and money and women and so on. The chimp is presumably just thinking about the banana. In that sense it’s a cheap equation: She is deliberately ignoring or contradicting Marx’s famous maxim that the worst house built by a person is still superior to the best house built by a beaver. One can argue with that, but you see what he means right away.

I realize I’m getting into a seemingly irrelevant tangent here, Matt, but my point is that I think Kael falls in love with her contrarianism sometimes, with her desire to defy what she sees as the conventional wisdom of the upper-bourgeois readers of the New Yorker. That leads her sometimes into brilliant insights and other times into dunderheaded dead ends.

Matt: Such as what? Everybody who reads her has a list of examples. Mine would include her generalized hostility toward Stanley Kubrick — especially “2001,” which I think she entirely misunderstood — and a sort of anti-intellectual upper-middle-class yahoo-ism, which was quite hostile toward a lot of the 1960s European art cinema without which a lot of the ’70s American films Kael adored would not have existed. And there was also a homophobic strain to a lot of her writing on films with gay characters and themes, which was by no means unique but certainly contrasts poorly with her very advanced, matter-of-fact writing about films with black and Hispanic characters.

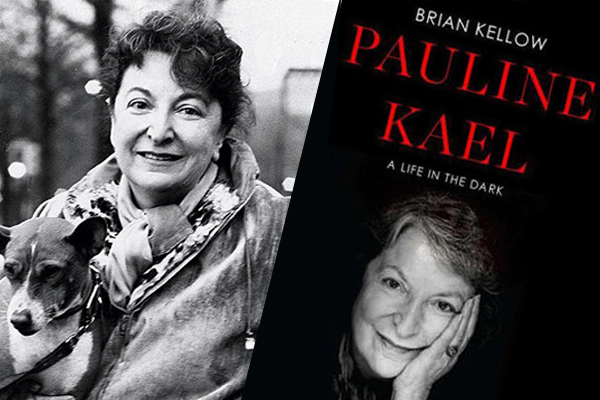

The new Pauline Kael biography by Brian Kellow gets into this a bit, and it’s not flattering to Kael at all. At one point he quotes Kael’s review of the 1968 film “The Sergeant,” starring Rod Steiger as a tormented military officer who develops a damaging crush on a private. She writes, “There is something ludicrous and sometimes poignant about many stories involving homosexuals. Inside the leather trappings and chains and emblems and Fascist insignia of homosexual ‘toughs’ — [check out those ironic quotes!] — there is so often hidden our old acquaintance the high-school sissy, searching the streets for the man he doesn’t believe he is. The incessant, compulsive cruising is the true, mad romantic’s endless quest for love.” You can feel her going for empathy and understanding in that passage, but it’s really condescending.

Andrew: That’s really pretty awful. One probably shouldn’t resort to biography in a case like this, but it may be instructive to remember that Kael lived for several years as a young woman with the poet and radical filmmaker James Broughton, who was primarily gay but fathered a child with her. It’s extremely tempting to reconsider her attitudes about homosexuality and her hostility to avant-garde or art cinema in that light!

Matt: The biography barely gets into that, by the way.

Andrew: “Anti-intellectual upper-middle-class yahoo-ism” is stronger than whatever I was going to use, but pretty well sums it up. You know, I can understand where she was coming from, as a girl from a modest and relatively rural California background, who often felt alienated by the phony-baloney tastes of the Eastern elite establishment. She believed passionately in movies as mass entertainment that could still be humane, and believed that the power of actors and even movie stars could transport us emotionally in a way no other craft could or would. It isn’t precisely my aesthetic, but I completely respect that.

But as you say, she couldn’t see why cinema that was more formal in its orientation, and wasn’t aiming for a mass audience, was important in a different way, and that the possibilities of the medium were not limited to the upper-middle Hollywood and off-Hollywood movies she loved best. She rejected most of the most ambitious areas of European art cinema, as you say — with the bizarre exception of early Godard. (She was a sucker for a certain strain of French movies, maybe because of the sexual frankness.) You mentioned her inability to get Kubrick, and you could extend that to Terrence Malick. I could be wrong about this, but I think she never even wrote about Andrei Tarkovsky, and may never have seen his films. (She certainly would not have enjoyed them!) And then there is the question of the directors who could do no wrong, in her eyes.

Matt: If you look back over her collected work, yeah, it is pretty light on foreign films after the late ’70s. She seemed to almost lose interest entirely in anything non-Hollywood after about 1982, with the exception of certain American independents that she championed. She wrote one of the best and least condescending reviews of Spike Lee’s first film “She’s Gotta Have It,” a great example of where her sexual frankness and her wannabe-boho fascination with images of blackness converged in a really distinctive, fun way. She was more comfortable writing about African-American characters and stories than almost any other prominent film critic of the time, except maybe Roger Ebert. That makes up for some of the exoticism that hampers other reviews — describing Louis Gossett Jr. in “An Officer and a Gentleman” as being like Woody Strode — a superior being or a representative of a more evolved race or something. But I like that she just puts that kind of stuff in reviews — “Did I say that out loud?”-type comments. So many major critics are much more careful, so obviously very worried about how they come off in print, as if they’re running for office. Kael didn’t care about any of that, for better or worse.

Andrew: Yeah, the uninhibited quality of her voice is something I largely admire, partly because anybody who’s written a lot of reviews understands how much work was required to make it sound artless. And yes, she was a fearless champion of what we might call American independent cinema, long before the term existed or the concept became trendy. (I’m guessing she disliked the label.)

And amid the criticisms that we might have, let’s remember that she was absolutely ruthless in attacking the greed and stupidity of Hollywood’s blockbuster mentality, especially because she believed the commercial enterprise of movies was capable of producing a beautiful and unique kind of alchemy. As the studios increasingly defaulted to formula from the late ’70s onward — or, let’s say, to a set of formulas Kael saw as a betrayal of Hollywood’s soul — I think she began to see that attacking the highbrow tastes of people on the Upper West Side was less and less relevant. Didn’t she remark at one point that had she known trash culture would become the only culture, she wouldn’t have defended it so vehemently?

Matt: Yes, she did say that. Quite a mea culpa, really.

You’re really not a fan of hers, are you? I mean, you defend her in the abstract, but I get the sense that you’re very distrustful of what her kind of accessible, personal criticism represents, even though you’ve learned a lot from it.

Andrew: I appreciate what she represents and her influence on the craft and form of film criticism, mine very much included, is almost oxygen-like. But I’m not really on her wavelength. Even when I agree with her about certain movies or directors I often don’t see them the same way, and don’t really get what she’s talking about. I’ve honestly never known what she means by “humanist” movies, and I don’t understand her passion for, say, Brian De Palma or James Toback. Such weird and ultimately minor choices! And the way she uses the first-person plural or the second-person plural, to implicitly include the reader in her highly eccentric emotional response — that drives me nuts. It’s manipulative and a little creepy, like she’s saying all right-thinking people will have the same opinion about a motion picture.

Matt: I used to do that all the time, using the royal “you” — then I started trying to break myself of it, and finally I started using it again without guilt, as an alternative to “one,” which is grammatically correct and more accurate but always sounds stuffy to me.

As recently as 10 years ago, there were certain critics who knew Kael or who were directly mentored by her who all got grouped under the heading of “Paulettes” — people like our former colleague Stephanie Zacharek, and Charles Taylor, Michael Sragow, David Edelstein, my former New York Press colleague Armond White, and David Denby, who inherited Kael’s chair at the New Yorker. That’s funny to me, because the reality of film criticism is that lot of critics are, to some extent, Paulettes, even if the critic never personally knew her. Her voice is just that strong. Even if you choose to define yourself against Kael, you’re acknowledging her influence. It’s like deciding to become a jazz trumpeter and not be influenced by Miles Davis, or becoming an actor and trying not to be influenced by Brando. She has that kind of effect, an elemental effect, transformative and deep. The most recent crop of young film critics definitely have a touch of her style or outlook. They could not avoid it if they wanted to. Reading them, you might also detect bits and pieces of other critics who had an impact of some sort: Manny Farber, James Agee, Molly Haskell, Roger Ebert, Andrew Sarris, Francois Truffaut, even the borderline stand-up comedy-type reviewers like Anthony Lane, and Outlaw Vern and his spiritual godfather, Joe Bob Briggs. They all meant something to writers who came later. They had an impact, though perhaps not on the level of Kael who has been absorbed into the collective subconscious.

But I wonder, Andrew, do you think that deep influence is an altogether good thing? Or is it a bad thing?

Andrew: Well, since I’ve been playing the role of the hater here a little bit, I’ll say that while Kael’s work is a mixed bag and I often find her judgments on individual films, directors and genres baffling, she made film criticism seem relevant and interesting to large numbers of people in a way nobody had before her. She made Roger Ebert possible, and I’m quite sure Roger would agree with that. In a general way, her influence has been highly positive, and what I mean by a general way is that anyone who tries to write about movies in a direct and colloquial voice but also with erudition and style, anyone who seeks to combine personal observations and social or political criticism in a movie review, anyone who is working to situate this peculiar and seductive art form in relation to the world and to human life owes an enormous debt to Pauline Kael.

Now, here’s the downside, Matt: I think when it comes to the highly specific vision of cinema and aesthetics applied by Kael and some (not all) of the admirers you mention, her influence is way more problematic. She wrote so often about valuing beauty and pleasure in the movies — who can argue with that? Well, I can, when beauty and pleasure are defined so narrowly as to refer almost entirely to the kinds of well-made, sophisticated entertainments built around attractive actors playing likable characters, which was what she liked best. I’ve always felt that Kael did not approve of people who found beauty or pleasure in radically different kinds of films — she never used the word “film” of course, as she found it pretentious — and suspected that we were lying about it or fooling ourselves or mistaking suffering for pleasure.

As we’ve discussed, her definition excludes all kinds of things, from European art cinema to horror movies to a lot of crime films and other genre movies. What troubles me about her legacy is the anti-intellectual component you have mentioned, the idea that Kael provides cover for the persistent critical devaluation of movies that challenge her definition of “movies” because they do not set out to please or entertain millions of people, and may be unsettling or incomplete or unfriendly on purpose.

Now it would be ludicrous to suggest that Hou Hsiao-hsien or Alexander Sokurov or Kelly Reichardt or whoever you want to pick from world cinema remains totally obscure because of Pauline Kael’s ghost. But I see her populism — which she meant as a rebuke to the wealthy and powerful — increasingly employed after her death as a weapon of reverse snobbery that makes common cause between critics, moviegoers and major media corporations, a weapon used to support a very limited and mainstream vision of cinema and drive all others ever further into the margins.

Convince me that I’m wrong.

Matt: I don’t think you’re entirely wrong. Kael said near the end of her life that, in effect, that the war described in her piece “Trash, Art and the Movies” ended at some point, and trash won, and that maybe she felt guilty that trash won, and wondered if she’d played a part in that victory. I doubt she would have praised a lot of the big, loud comic book movies that dominate box office charts today — she was negative on the original “Star Wars” films and very mixed on the original Tim Burton “Batman,” which feels quite old-fashioned, even classical, compared to comparable movies today: “The Dark Knight,” “Inception,” “Avatar” and the like. And I am not sure that her definition of a good film necessarily “excludes all kinds of things,” as you claim.

But you’re right that she naturally gravitated toward certain films and filmmakers. That was her nature. I gravitate toward certain kinds of films and filmmakers. You do, too. All critics do. But I don’t know anyone who is a remotely serious movie watcher who only reads one critic. Brian Kellow’s biography gets into this quite a bit. Kael liked to feel overwhelmed by movies. That naturally meant that she clicked with films that were more emotional and visceral than cerebral or analytical. She detested almost everything that smacked of academia, abstraction or agitprop, unless those qualities were subordinated to what the Kellow biography calls “kineticism.” She loved Sam Peckinpah, Robert Altman, Steven Spielberg and early Martin Scorsese, though she felt Scorsese became too arty and careerist too early and lost his way, which is critic code for “became interested in things that I don’t care about.” Her big complaint about “Raging Bull” was that it was “aestheticized pulp” and that it therefore lacked vitality. Vitality was everything to her, so important that it led her to distrust any movie that set out primarily to make one think and reflect.

The titles of a lot of her collections spell this out: “Reeling,” “When the Lights Go Down,” “Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang,” “Taking It All In.” They’re blatantly sexual, teasing. They’re a caricature of what macho guys claim that women “need” — i.e., to get laid. It’s no huge shock that Camille Paglia worships Kael and does her own version of the Dionysius-goes-to-the-

But Andrew, I think it’s really important to point out that this is what all critics do, even if they pretend they aren’t doing it. There is no correct way to review a movie as long as the writer has a moral compass and a firm grasp of film history and aesthetics — which Kael definitely had — and is honest. I wrote a piece for New York Press about Steven Spielberg a number of years ago in which I compared the directors I liked to friends, in the sense that most healthy adults have more than one friend, because we don’t get everything we need from just one friend, humans being so complex and imperfect: “We have friends who are great at giving advice, but whom we wouldn’t trust to feed our cats when we’re out of town. We have friends who’ve deceived or betrayed us, but who are so resourceful and clever that we’d like to have them beside us in an unfamiliar city if our heart suddenly gave out. This same attitude can apply to movies — and moviemakers.”

That attitude can apply to critics, too. Kael was a great friend, even though I never personally knew her. I found her infuriating and bizarre and inconsistent a lot of the time, and there was a period of a few years when I was just kind of tired of her and didn’t want to be around her. I needed some space, I guess. Then I went back to her and appreciated her in a new way, and was able to reconcile my youthful worship of her with what I had learned from reading other critics, past and present. Reading Kael made me feel as though I was sitting across from her at a coffee shop or in a bar, listening to her talk about this film or that filmmaker, or about the wider world beyond the screen. Very few critics have her talent for intimacy and directness. She was an amazing person who enlightened, provoked and changed me. I miss her terribly.

Andrew: That’s great! You tell me I’m wrong while denying you’re doing so, a very Kaelian tactic! Well, a film-critic tactic anyway.