WASHINGTON (AP) — The Federal Reserve sketched a bleaker outlook Wednesday for the economy, which it thinks will grow much more slowly and face higher unemployment than it had estimated in June.

The Fed now predicts the economy will grow at a scant 1.6 percent to 1.7 percent for 2011. For 2012, it thinks growth will range between 2.5 percent and 2.9 percent. Both forecasts are roughly a full percentage point lower than its June forecast.

The Fed sees unemployment of between 8.5 percent and 8.7 percent next year. In June, it had predicted unemployment would drop next year to as low as 7.8 percent. The rate is now 9.1 percent.

The Fed's gloomier outlook is similar to many private economists' forecasts. Bank of America Merrill Lynch, for example, expects only 1.8 percent economic growth this year and 2.1 percent in 2012.

Those growth rates are far too low to drive down unemployment.

Even so, the Fed said after its policy meeting that the economy had improved since nearly stalling in the spring. As a result, it's putting off any new actions so it can gauge the impact of steps it's already taken.

Fed policymakers made the announcement after a two-day meeting.

In a statement, the officials said consumers have stepped up spending. Still, they said the economy continues to face significant risks, including the debt crisis and risk of recession in Europe.

The Fed left open the possibility of taking further steps later to try to boost the sluggish economy. But it gave no hint as to what those moves might be.

"They're noting the better growth numbers but remain pretty cautious," said Michael Feroli, a former Fed economist now with JPMorgan Chase & Co. "They're not celebrating by any means, which probably is appropriate."

The vote was 9-1. Charles Evans, the president of the Chicago Federal Reserve Bank, dissented. The statement said Evans wanted to take stronger action to try to boost the economy.

The vote was a shift from the previous two Fed meetings, when three members had dissented for the opposite reason: They opposed the Fed's continued efforts to keep rates at super-lows, for fear it could ignite inflation. Those three members, known as inflation "hawks," dropped their opposition this time.

Some analysts said the shift didn't necessarily mean the Fed is any likelier to take any additional action soon to try to boost the economy.

"The view of the hawks is that once the decision has been made by the majority, it just causes confusion if they continue to vote to roll back action that has already been taken," said Paul Ashworth, chief U.S. economist at Capital Economics.

Some analysts said they expected the Fed to take further action to support the economy at coming meetings, given their expectation that growth will remain sub-par.

"Policymakers are keeping the door open because the unemployment rate remains high, and there are clear downside risks from the economic situation in Europe," said Sal Guatieri, senior economist at BMO Capital Markets.

After their September meeting, the policymakers said they would shuffle the Fed's investment portfolio to try to further reduce long-term interest rates. And in their previous meeting in August, they had said they plan to keep short-term rates near zero until at least mid-2013, unless the economy improved.

The Fed repeated the mid-2013 target in its statement Wednesday. It also said it was continuing its program to rebalance its portfolio to try to lower long-term rates.

The Fed has kept its key short-term interest rate at a record low since December 2008. This is the rate that banks charge on overnight loans. It serves as the benchmark for millions of business and consumer loans.

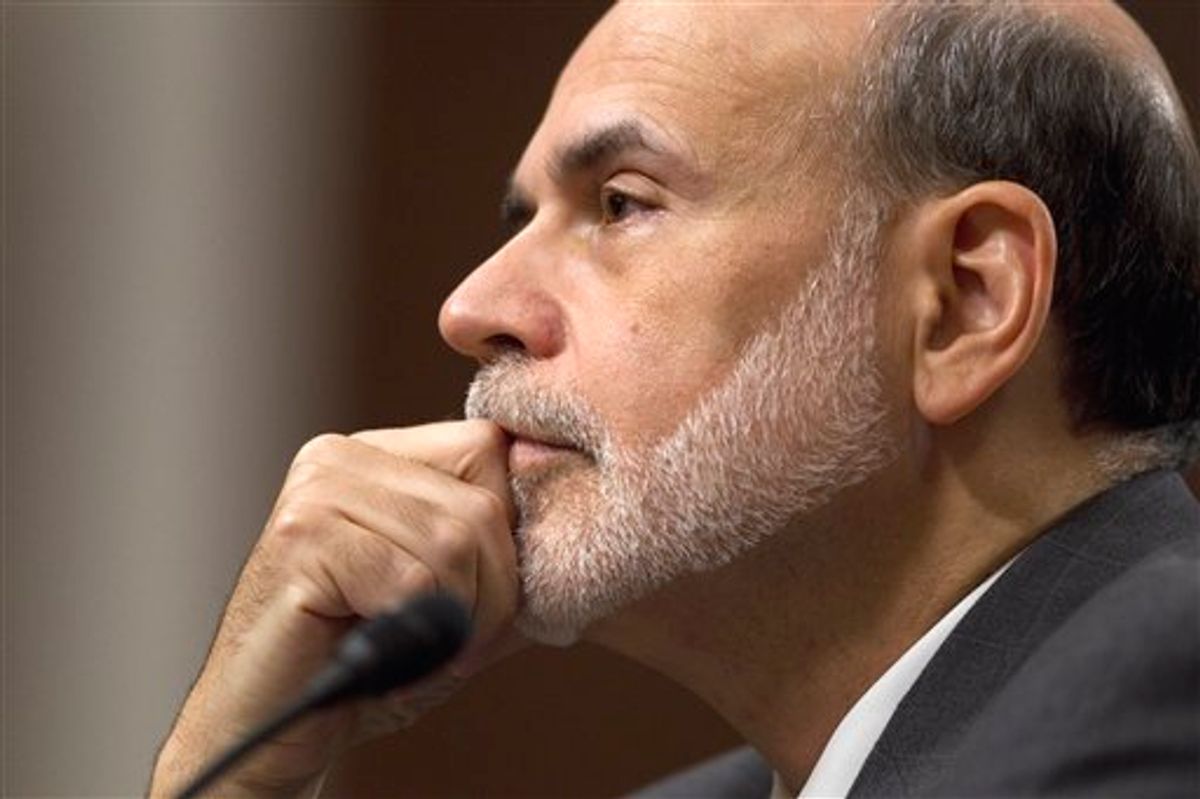

Later Wednesday, the Fed will also release its economic forecasts, and Chairman Ben Bernanke will hold a news conference.

The Fed noted that growth strengthened over the summer, in part because temporary factors that had weighed on the economy in the spring had eased. Consumers are able to spend a little more because gas prices have declined from their May peak of roughly $4 a gallon. And auto sales and production have picked up now that supply chains disrupted by the March earthquake in Japan are flowing more freely.

But the Fed said the job market remains weak. And it suggested that the troubles in Europe could hurt U.S. growth.

The debt crisis in Europe could force the Fed to lower its economic projections. The Greek prime minister's surprise move to call a referendum on the country's latest rescue plan sparked fears that the debt deal could unravel, that Greece could default on its debt and that the crisis could infect the global financial system.

Even if Europe dodges a financial catastrophe, many economists think it's headed for a recession that would affect the U.S. and global economies. The Fed expressed such concerns after its August meeting.

Still, the Fed remains deeply divided over what, if any, action to take next.

The actions taken in August and September were adopted on 7-3 votes, the most dissents in nearly 20 years.

Three regional bank presidents — Richard Fisher of Dallas, Charles Plosser of Philadelphia and Narayana Kocherlakota of Minneapolis — all voted no. They have expressed concerns that the Fed's policies could lead to high inflation later.

On the other hand, Vice Chair Janet Yellen, Governor Daniel Tarullo, Evans and New York Fed President William Dudley have said the economy is at risk and might need more support.

Two officials pushed for bolder action at the September meeting, according to minutes. The members discussed more bond-buying. Some said it should remain an option.

A brighter outlook for the economy has given the Fed more room to wait. The economy grew at an annual rate of 2.5 percent in the July-September period — the best quarterly performance in a year. That was largely because consumers increased their spending at triple the rate from the previous quarter.

The growth is strong enough to show that the economy isn't about to slide into recession. Still, growth would have to be nearly twice as high — consistently — to make a major dent in the unemployment rate, which has been stuck at 9.1 percent for three straight months.

Evans has proposed that the Fed set benchmarks for raising rates. For example, it could agree not to raise short-term rates until unemployment fell below 7 percent or the outlook for inflation exceeded 3 percent. The unemployment rate has hovered around 9 percent for more than two years, and the Fed's inflation outlook is under 2 percent.

___

AP Economics Writers Christopher S. Rugaber and Daniel Wagner contributed to this report.

Shares