Once or twice a year, the most peculiar mail-order catalog ever published was stuffed into canvas bags and thrown off mail trains across the United States. Between its covers were the nuttiest, most bizarre inventions and prank devices ever offered for sale.

Had you been a high-ranking clerk of a fraternal lodge at the end of the nineteenth century or early twentieth century, you would have retrieved from the post office one of these little catalogs every now and then. Published by the DeMoulin Brothers Company of Greenville, Illinois, in limited numbers to a very specific readership from 1896 to 1930, these catalogs of fraternal initiation devices and regalia were inaccessible to the public—practically unknown. If the catalogs were as scarce as hens’ teeth then, they are as scarce as goats’ feathers now.

“Men need fun and entertainment. They are going to get it somewhere,” boldly asserted one of the DeMoulin catalogs. With regard to fraternal brethren, that was often the case. Life and health insurance benefits were the main reasons men joined the popular fraternal groups of the day, but fraternizing and fun was also paramount. If there wasn’t enough of that at their local lodge, they would join another lodge, or find other forms of entertainment—perhaps less wholesome.

In short, a lodge without interesting entertainment wasn’t worth “a hill of beans”; it was in danger of being called “sleepy” or “puny” and then “dead.” As population centers and wayward burgs popped up on the prairie, ridge, and shore, so did lodges of fraternal orders like the Odd Fellows, Masons, Knights of Pythias, Woodmen, and so forth. These lodges were central to the economic and social well-being of their communities. But their success depended on membership: a packed hall with new members wanting to get in. Thus, it made sense for lodges to offer something to keep members looking forward to meetings.

In 1892, when fraternal membership began to surge, competition among lodges to attract and keep members intensified. It didn’t take long for Ed DeMoulin to realize this. A witty, grown-up whiz kid and inventor, he set to work to “amp up the action” at his local lodge in Greenville. In a matter of weeks, Ed’s Moulten Lead Test made a successful debut with the brethren of the Modern Woodmen of America.

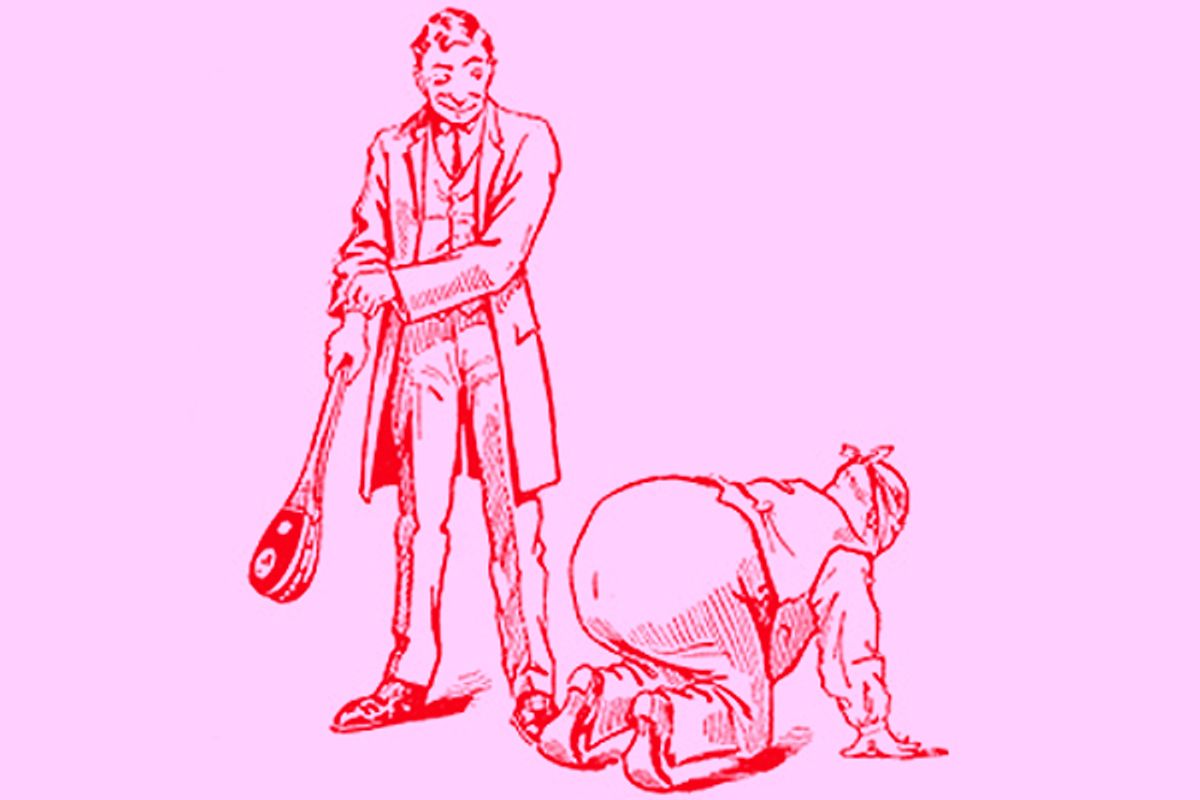

Thus, at the intersection of two historic eras—the Age of Invention and the Golden Age of Fraternity—the DeMoulin Brothers Company was born. Within a couple of years, members of Ed’s lodge were in the habit of gleefully witnessing new candidates initiated with Ed’s peculiar inventions—the Roller Coaster Goat, the Saw Mill, or the dreaded Branding Iron. In 1894, the Greenville Advocate wrote, “Ed DeMoulin is sure enough an inventive genius ... Go in, Ed, there’s millions in it.” So he did. Ed was fairly typical for the time. The U.S. patent office was registering an average of thirty-five thousand patents per year. But patents for prank devices were an anomaly during this era of practical inventions for farm, home, and business.

Following the example set by Aaron Montgomery Ward in 1872, Ed and his brother Ulysses used the mail-order concept to drive their business. In 1895, they mailed their first catalog. It was a huge hit. Before long, the DeMoulins’ catalogs were mailed regularly to lodges of many different orders all across the country. Adorned with beautiful covers, the catalogs were welcomed by high-ranking officials wanting to “heat up” their lodges. Orders for eccentrically wheeled mechanical goats and electric shocking and exploding contraptions flooded the DeMoulins’ front offices. Goods, boxed in padlocked wooden crates and loaded onto train cars, were shipped to nearly every state.

Today if you happen to be in the market for an exploding pie table or a Human Centipede—a large four-passenger harnessed affair built of canvas and wired for a “hot” ride—or other peculiar invention, you’re a bit late. The best I can do is take you back a hundred years via twelve specially selected DeMoulin Brothers’ catalogs and show you what your hard-earned dollars could have purchased.

What is it, though, that makes the DeMoulin catalogs so precious and outrageous? I suppose it is our temporal distance from them, our general unfamiliarity with the subject matter. Their pages serve as a sort of spyglass to gaze upon middle-class America at the turn of the century—and a secret segment of it to boot.

Julia Suits is a New Yorker cartoonist and freelance illustrator.

From "THE EXTRAORDINARY CATALOG OF PECULIAR INVENTIONS" by Julia Suits. Published by arrangement with Perigee, a member of Penguin Group (USA), Inc. Copyright (c) Julia Suits, 2011.

Shares