There's no shortage of books promising to explain the most populous nation in the world to Western readers, fat, solemn tomes crammed with names, numbers, events and predictions. "China in Ten Words" by Yu Hua, on the other hand, is a slim volume, and a lot of it concerns Yu's childhood in a backwater town during the Cultural Revolution. You'll find a few statistics scattered over these pages, but far more of those peculiar modern yarns that reside in the netherland between gossip and news report. Nothing tells you more about a people than the stories they like to swap: the old peasant patriarch who could not countenance the price of a BMW 760Li until the dealer explained that it took two cows to supply the leather for each of its seats, the female Mao impersonator who spends hours perfecting her makeup and learning to walk in elevator shoes.

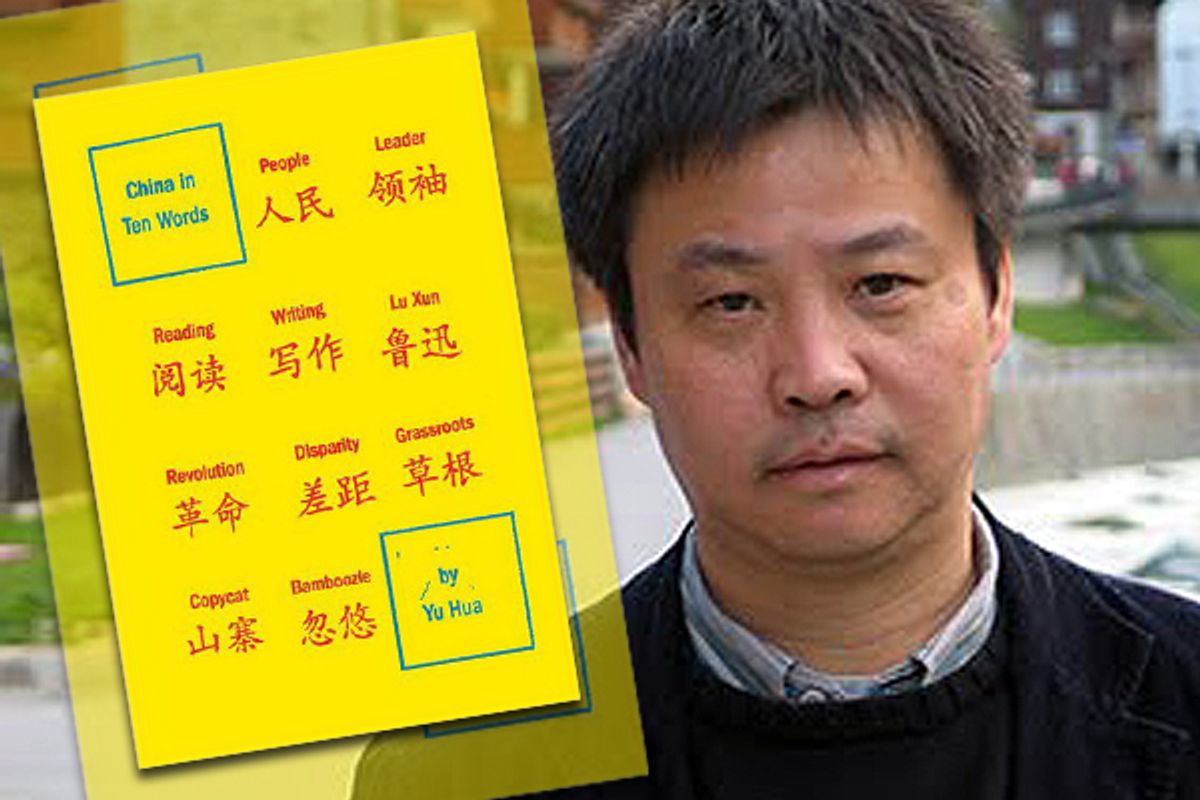

"Here," Yu writes of his homeland, "where everything is tinged with the mysterious logic of absurdist fiction, Kafka or Borges might feel quite at home." One of China's most celebrated novelists (he's best known in the U.S. for the novels "To Live" -- made into a film -- and "Brothers"), Yu has a fiction writer's nose for the perfect detail, the everyday stuff that conveys more understanding than a thousand Op-Eds. "China in Ten Words" is a series of linked essays, each of which considers a word whose meaning has evolved over the course of Yu's lifetime, as China transformed itself from a command economy to a market economy. Things have changed a lot, he explains, but not necessarily in the ways you might think.

Perhaps the most bewitching aspect of this book is how funny it is, especially in the first few (and most autobiographical) chapters. In China, Yu has been praised for his "plain narrative language" -- a product, he jokes, of his desultory education during the Cultural Revolution; he simply didn't learn very many Chinese characters. "Life is often this way," he writes: "you may start off with an advantage, only to box yourself in over time, or sometimes you may start with a handicap, only to find it carries you a long way." For a plain-writing man, Yu has an exquisite, cosmopolitan sense of irony; in Allen H. Barr's sensitive translation, he comes across as an Asian fusion of David Sedaris and Charles Kuralt.

In the chapter titled "Reading," he remembers his boyhood hunger for books; most of the local library's holdings had been burned by the Red Guard, who spared only 20 works of "so-called socialist revolutionary literature." Thinking of the university students who ate leaves during the Great Famine of 1958-62, Yu writes, "Just as the famished students stripped the campus trees bare, so I devoured every one of those grim, unappetizing novels." (The mock-Homeric metaphor is one of Yu's fortes.) One summer, he could be seen poring obsessively over "The Selected Works of Mao Zedong," which earned him the reputation of a political scholar; in truth, he'd discovered the footnotes to an otherwise tedious text; they summarized historical events and biographies, and were the closest things he could find to decent stories.

When he was older, a few battered, samizdat copies of real novels passed through his hands, with "a dozen or more pages missing from the beginning and the same number missing from the end," each one a "headless, tailless thing, without author or title, beginning or ending." The lack of resolutions, in particular, tormented him, and Yu traces the dawn of his own literary impulses to the hours he spent in bed at night, imagining how the stories might turn out. To this day, he occasionally picks up a classic and realizes it is one of those long-lost, tantalizing novels and now, finally, he can find out what happened.

Another fixture of Yu's early literary life were "big character posters," broadsides plastered on the public streets. These began as high-minded, if doctrinaire, political rhetoric, but over time they degenerated into ad hominem exposes aimed at rival factions, frequently accusations of sexual misconduct. Yu became expert at spinning the sketchy insinuations of adultery and other forms of hanky-panky into "more colorful, enhanced versions" for his friends. "For me," he observes drily, "the big-character posters functioned primarily as a form of erotica."

If there is one thing that Yu finds most endearing in his countrymen, it's this knack for turning the most unpromising material to the most unlikely uses. Whether he's recalling growing up in a ramshackle provincial hospital, napping on the morgue slab on hot days or sneaking into the operating room with his brother while his surgeon father was at work ("'Get out of here!' he would yell when he discovered us, and we would scamper away") or noting that nowadays Chinese economic life is "full of kings: the Paper Napkin King, the Socks King, the Cigarette Lighter King," Yu zeroes in on the incongruous. In the cracks between the expected and the actual is where his China thrives.

The later chapters of "China in Ten Words" explain two paradoxical concepts, translated as "copycat" and "bamboozle." The first signifies not just piracy and knockoffs, but also satires or spinoffs. For the Chinese, the term has "connotations of freedom from official control" and "an anarchist spirit." At times, the copycat can be more authentic than the original, as when a small mountain village -- inspired by the patriotism leading up to the Beijing Olympics but insufficiently influential to figure in the official torchbearer's route -- staged their own torch relay, in which every villager was allowed to participate. Video of the event became an Internet sensation.

To "bamboozle" is to con or to swindle, but with sufficient style and chutzpah to command admiration. A preposterous newspaper article about Bill Gates renting a Beijing penthouse for an astronomical rate was "able overnight to convert an obscure housing development into an apartment complex famous all over the country." No one is called to account for such lies, because "in China people just shrug it off as bamboozle," meaning, in this case, "both deception and hype" but also "a certain element of entertainment." According to Yu, the Chinese have a saying: "You don't have to pay tax on bullshit. That being so, why not bullshit to the max?"

Though he marvels at their resourcefulness and panache, Yu is not untroubled by his countrymen's blase acceptance of fraud as "performance art." His memories of the Cultural Revolution segue from nonsense to queasy horror as readily as Lewis Carroll's Queen of Hearts transitioned from croquet invitation to death sentence, but the god of the marketplace can be just as cruel. "So intense is the competition and so unbearable the pressure," he writes of the current moment, "that, for many Chinese, survival is like war itself."

The nagging question behind all this is whether they can survive their own survival. In one of his preternaturally apt anecdotes, Yu reports that some local governments have taken to raising money by selling "vanity" street numbers. Chinese folklore holds that the numbers 6 and 8 are auspicious, and for a fee you can change your address to No. 8888, even if your house actually stands between Nos. 12 and 13. What the homeowner gains in good luck, the community loses in people being able to find their way around its streets.

In the West, "China" has become a comedian's code word for the incomprehensible future, a monolithic economic juggernaut whose mention provokes nervous laughter. Yu's revelation -- that the Chinese often find their own society bewildering, self-contradictory and ridiculous -- ought to be unsettling, but instead it's reassuring. We know these people; like us, they're improvising into the future, with only the faintest idea of what they're doing, and with a propensity for scrambling the signposts even before they've figured out the way.

Shares