To understand the distance that the Republican Party has traveled on criminal justice, observe the record of Texas’ longest-serving governor.

In 2001, just after Rick Perry assumed the job, he vetoed a bill that would have ended the practice of arresting those suspected of class C misdemeanors — fine-only crimes that don’t require jail time, such as traffic offenses.

But fast-forward to 2007. That year, he signed a law allowing police officers to issue citations instead of making arrests for certain class A and B misdemeanors, including marijuana possession. Perry’s reversal came about in part because the state faced a projected shortfall of 17,000 inmate beds.

In Texas and other red states, formerly law-and-order GOP lawmakers are taking the lead in reforming criminal justice systems.

That shift is the result of two curves sloping in opposite directions — a dramatic fall in crime rates and exploding state spending on corrections (the second-fastest-growing category of state spending behind Medicaid).

So should a Republican win the presidency, a return to get-tough approaches seems unlikely. Yet ill-targeted budget cuts or sensational crimes linked to reforms still could take policy in the other direction.

Conservative crosscurrents

At the federal level, changes in the GOP’s stance have shown up in Republican support for “smart-on-crime” legislation. That includes the Second Chance Act, passed in 2007 to offer services that could help prisoners reentering society, and last year’s Fair Sentencing Act, which reduced the disparity in prison terms for possession of crack and powder cocaine.

National conservative leaders have been outspoken for other reforms, too. In 2009, Grover Norquist and David Keene, who head the Americans for Tax Reform and the National Rifle Association respectively, testified before a House Judiciary Committee in opposition to mandatory minimum sentencing policies.

Last December, conservative reformers launched a new vehicle for their efforts -- Right on Crime, a statement of principles signed by leaders like Newt Gingrich, Jeb Bush, Bill Bennett and Ralph Reed.

It calls for victim-offender mediation where appropriate, substance abuse treatment for nonviolent drug offenders, geriatric release programs for certain older offenders and other changes. The initiative is designed to embolden politicians of both parties who are considering reform legislation, Pat Nolan, vice president of the conservative-leaning nonprofit Prison Fellowship and a signatory to the statement, told the Crime Report. (Right on Crime has no official spokesperson.)

But conservatives also have a history of being swayed by the concerns of prosecutors, who Nolan says often oppose reforms. That’s because harsher laws and mandatory sentencing guidelines give district attorneys more tools to force plea bargains.

Asked in April about alternative sentencing, for example, National District Attorneys Association board chair Jim Reams told the Washington Times, “The assumption is that these are all choir boys at the prison, and if we let them out, all will be well. And it doesn’t work that way. We’re getting exactly what we deserve when we do this: we’re getting more crime.”

To date, the Tea Party wing has sat out this tug of war and hasn’t taken a general position on criminal justice policy. “I've not heard the issue discussed much in the movement,” says Mark Meckler, national coordinator for the largest group, the Tea Party Patriots.

Nolan says there have been no formal discussions between the Right on Crime group and the Tea Party.

A GOP White House and reform

Should a Republican president take on criminal justice reform, he or she would be helped by state experiences so far.

Many legislators who are “alumni” of state reform efforts are moving up to national politics and will champion new national legislation based on what’s worked at home, says Nolan. That will create a more favorable climate for change in Congress.

One priority under a Republican administration would be limiting the number and reach of federal criminal laws.

Tackling such “over-criminalization” likely would be a target for a Republican president, says Tim Lynch, who directs a project on criminal justice at the libertarian Cato Institute in Washington. “I think you’d be less likely to see new federal criminal statutes come along with a conservative in the White House,” he says, citing a federal 2009 hate-crimes law and the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation as examples.

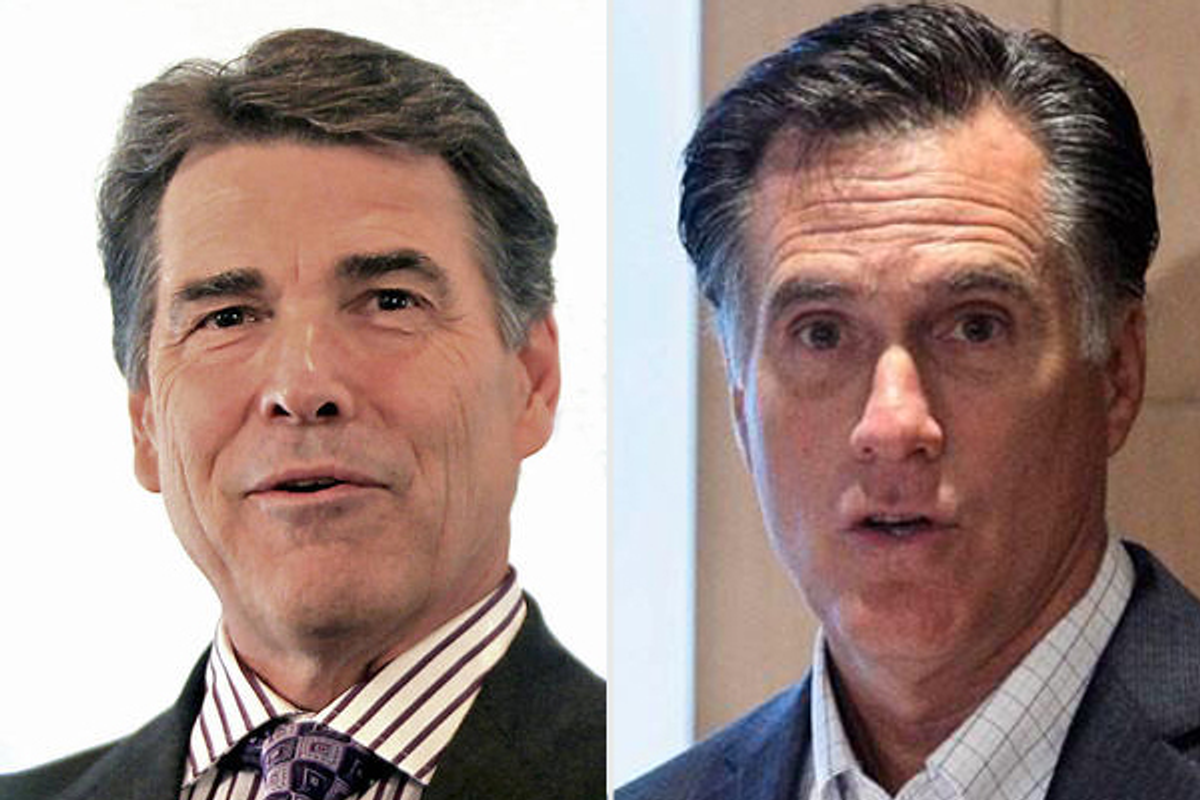

Whether a Republican president signed on to reform measures also would depend on which contender won. As former governors, Perry and Mitt Romney have legislative records that suggest they’re open to change. Perry’s death-penalty record (presiding over more executions than any governor in modern times) obscures reform-minded legislation he’s signed.

That includes a 2003 law mandating probation on the first offense for low-level drug offenders and 2007 legislation that gave incentives to probationers to complete substance abuse treatment.

Even so, one state advocate says Perry has been more a follower than a champion.

“Everything we’ve been able to get through has been because of the leadership of legislators on both sides of the aisle,” says Ana Yáñez-Correa, director of the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition. “Perry has not been an obstacle to the vast majority of those [laws], but he hasn’t been the person leading it either.”

During his four years as Massachusetts governor between 2003 and 2007, much of Romney’s energy on crime policy was focused on reinstating the death penalty for a narrow list of heinous crimes, while also establishing safeguards to protect the innocent. (That proposal never got through the Legislature.)

Romney also experimented with providing better reentry services for returning prisoners in major cities, according to his former secretary of public safety.

“I can’t really say how those turned out longitudinally, but the governor supported us in giving them a try,” Ed Flynn, now chief of the Milwaukee Police Department, told the Crime Report.

And Romney appointed a commission to reform the corrections system after the high-profile prison murder of a Catholic priest convicted of child sexual abuse; the group’s recommendations resulted in the firing of more than 100 guards for misconduct.

But during the 2008 presidential campaign, he also talked often of his get-tough credentials: As governor, he denied all 100 requests for commutations and 172 requests for pardons that crossed his desk.

The other leading candidates — Michele Bachmann and Herman Cain — have little or no paper trail on criminal justice. Bachmann has been predictably tough on social issues with a crime component — she opposed a 2009 anti-gay hate crimes bill — but she voted for the Second Chance Act. She also introduced a bill in the past three Congresses that would allow the FBI to share information about sex offenders with state and federal programs.

Cain has never held elective office, and his campaign did not respond to a request for comment on his position on crime policy. Georgia-based criminal defense lawyer Lee Sexton, a friend of Cain’s, says that though he doesn’t speak for the candidate, he anticipates Cain would take a look at issues like the over-incarceration of nonviolent offenders. But Sexton stresses that whatever his policy choices, Cain is an “advocate of the Constitution.”

Budget cutting

If a Republican president is to take the lead on a new approach, reform-minded conservatives think they have work to do.

“We recognize — those of us conservatives involved [in reform efforts] — that we’re key, and that if we’re going to have any reform, we’re going to have to provide the leadership and the cover for the political class to do that,” says Richard Viguerie, a well-known direct-mail conservative fundraiser and chairman of ConservativeHQ.com.

One Republican activist goes further: “Real reform will require Republican dominance,” asserts Eli Lehrer, vice president of the conservative Heartland Institute. “It will not happen under a Democratic administration.”

But under a GOP president, the possibility of a return to previous get-tough policies also is real. Though budget-cutting politics have worked in favor of changes like reducing prison populations, they also can do the opposite. In September, for example, the Senate Committee on Appropriations recommended eliminating funding for the Second Chance Act for fiscal year 2012, and the law has yet to be reauthorized after expiring last September.

For states considering investing in reentry programs, the loss of federal support could kill their interest.

And with a Republican in the White House, budget cuts at the U.S. Department of Justice would be more likely, says Lynch. Though noting that he can speak “only in the broadest strokes” at this stage, he thinks a Republican president would bring increased scrutiny of the department’s grants to state and local police departments, prosecutors’ offices and prisons.

Reform also has a long way to go among conservatives who actually hold power.

On Oct. 20, Senate Republicans defeated a bill to create a bipartisan commission that would conduct a complete review of the criminal justice system. Four Republicans voted with the Democrats, but it fell short of a filibuster-proof majority. Republican Sens. Kay Bailey Hutchison and John McCain argued that the proposal, sponsored by Virginia Democrat Jim Webb, would have trampled states’ rights.

“Even if a Republican were president and Republicans controlled both chambers, the environment isn’t conducive for [reform] yet,” says Viguerie, a Right on Crime signatory. “In the next 18 months to two years, that will change, but [conservative reformers] haven’t really engaged politically to bring along the leadership.”

Even with the setback on the Webb bill, in the short term there is at least one vehicle on which reformers can focus their efforts: a bipartisan, 18-member Senate Law Enforcement Caucus that formed in October. The group seeks to raise awareness and support in the Senate for effective state and local law enforcement initiatives, including more resources and dissemination of best practices.

Of course, 18 months is a lifetime in politics, and events outside the Beltway could radically change the political environment affecting criminal justice.

Conservatives like Nolan fear high-profile bureaucratic mistakes, for example, that could undermine their efforts.

“It’s our nightmare that somebody is released and does something horrible,” he says. “Any politician who supported something that took 6 months off of a sentence is subject to second guessing.”

“I think there’s a good answer to that,” Nolan continued, “which is that you can’t keep everybody locked up forever ... But that’s a sophisticated argument, and it’s easy to attack that person. Our fear is that as a result, all of our good bipartisan work could go up in smoke.”

Shares