My naked pelvis was 3 feet away from an 80-year-old grandfather wearing a sweater vest. Men who attend art classes must be the world’s primary consumers of sweater vests; it’s like they’re in Joseph Gordon Levitt costumes all the time. The muscle in my leg twitched as the old man squinted at me, stared at his drawing and then turned to the instructor. “I can’t get it," he said. "I just can’t quite do the lines of the elbow.”

No surprise there. These are the body parts 80-year-old men in life drawing sessions will admit they don't know how to draw: elbows, noses, foreheads, earlobes, shoulders, collarbone.

These are anatomical parts 80-year-old men will not admit they don’t know how to draw: everything else.

After a few weeks, this man, or any number like him, would come up to me on a break and tell me, very tentatively, that I reminded him of his dead wife, or an old girlfriend, or a nurse in Korea. The art classes I modeled for were largely populated by retired seniors -- probably because they spanned hours right in the middle of the workday -- so this interaction happened enough times that you would think I’d have worked out a response. The response is that there is no right answer. My inclination was always to say, “I bet you saw her naked a lot, buddy!” and then elbow him jovially in the ribs. I did not do that – mostly because you don’t know how sturdy 80-year-olds' ribs really are. Instead I tried to smile and be polite.

Though there were times when knowing what to say was tricky, like when one man shuffled over and informed me that I reminded him of a “good time girl named Samantha from the old Times Square.” I believe I replied that I was a fan of "Bewitched," and we both agreed that was a pretty good show.

But that was as sexual as nude modeling for art classes ever got. People who have never modeled seem to think the moment you drop your robe on a podium, art students immediately decide you are their muse and just start sending you earlobes by the dozen. That’s obviously untrue – in the entire time I spent modeling, I received maybe three earlobes, tops. Most of the classes had been so thoroughly instructed not to make the model feel uncomfortable that they’d avoid even looking at you during the five-minute breaks between poses, which made little sense, as it was the only time I wore a robe.

It’s not that I particularly loved being naked. For one thing, it gets rather chilly in those studios. And I probably wouldn’t lounge around my apartment without clothes. When I'm alone, I wear a snuggie, just like everyone else. But I loved the way being in that art studio naked seemed to reinforce that this place was not like the world outside. If you strip on the street, I imagine you’ll get hauled away to jail. If you do it at a party, well, I guess people will assume it’s that kind of party. I liked that in here, if nowhere else, I could be naked without anyone saying or doing anything. I loved the way everyone in that room had somehow reached some tacit agreement that my lying around on a couch naked all day, pausing only to eat a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, was the most natural thing in the world.

I was happy to sit still and ignore reality, too. Which was why I was 22 and modeling for art classes to begin with.

I had moved to New York with a liberal arts degree and a closet jammed with Lily Pulitzer dresses. My résumé was filled with summer internships at law firms. I had absolutely no idea what I was supposed to be doing with my life. I’d been deemed inept at writing -- for free -- for a New York-based beauty news website. (I didn’t include enough pictures of popular celebrity wedding hairstyles, which was an aspect of the writing process I hear Faulkner also struggled with.) I reckoned any dreams I had in the literary world were over. Meanwhile, I couldn’t think of anything else I was remotely qualified to do.

I made calls. I networked. I applied to Craigslist jobs and stood in the lobbies of office buildings watching people running in with coffee cups, looking frazzled and unhappy. I was terrified that if I made one misstep, I would be trapped forever in some sort of café-mocha-latte-balancing purgatorial state that Dante just “forgot” to mention.

It felt like I’d been running on a treadmill my whole life -- and then it just stopped. Maybe everyone feels this way during major life changes, but I floundered. I would stay up all night looking up facts about companies where I was applying only to forget every single one during my interview. I sent out letters and then discovered that I’d addressed them to the wrong person. Not only was I doing poorly, but I became convinced that, without a conga line of professors and family members pulling me along, I’d never be able to do anything well. I cried a lot. I always thought being a grown-up was going to be so easy – all Manolo Blahniks and ice cream for dinner, all the time. Looking back, that period was very brief, but it seemed like it could last forever.

One of the things that cheered me up, and also didn’t require leaving my apartment or spending any money, was looking at old art history books. I didn’t want to be an artist. I wanted to be inside a picture. In those paintings, everyone was so beautiful and so still. I loved Matisse’s “Luxe, Calme et Volupte” inspired by Baudelaire’s poem “L'Invitation au Voyage,” that says “there all is order and beauty, luxury, peace, and pleasure.” The people in that picture -- all pink and indigo, basking in one of those Don DeLillo sunsets -- they didn’t worry about whether they’d ever get health benefits. They didn’t panic over how to justify their existence to increasingly nervous parents. If there is a perfect opposite to “post-grad flailing panic,” it is that picture. It’s corny to say that I wanted to be a part of that world, but I did, I really did.

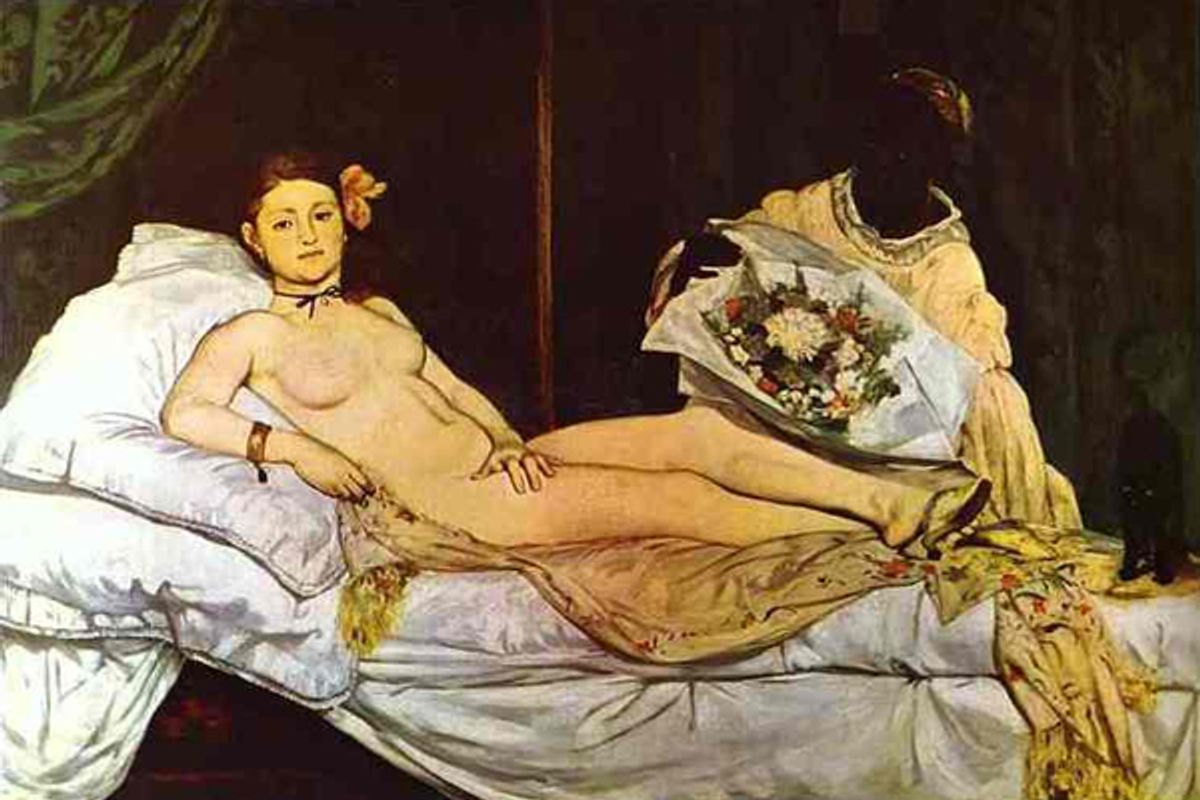

I loved Manet’s "Olympia," too, the way the model in the painting looked at you as though she had things all figured out. She looked as though she never worried over where her life was heading. She just lay on that bed, propped on pillows, rather indifferently allowing people to bring her massive bouquets of flowers. I imagined that she was a courtesan and probably died of TB. (It turns out she became a successful and admired artist in her own right.)

I wished I could disappear inside those paintings. I wanted to be calm and voluptuous, like the women in them, instead of worried all the time. When everything seemed like it could be a misstep, opting to do nothing seemed only logical. And better, surely, to wear nothing rather than a potential future I didn’t want and couldn't manage.

Besides, I already knew how to model. I’d done it for some casual classes in college. Twenty dollars an hour to sit and pose at one of the academies in New York might not have been a fortune, but the opportunity to duck out of the pressures of the real world and just be praised for reclining on a divan? Maybe with someone hovering behind me clutching a large bouquet of flowers? That seemed priceless.

So when, early into my first week of modeling, one of the instructors loudly intoned to the class, “This model -- she has interests, and is a person, and not bowl of fruit!” I wanted to reply, “No, for the time being, I’m cool being a pomegranate.”

And I was a good little pomegranate. For a while, anyway.

When I first started modeling I was determined to put Lisa del Giocondo to shame. The Mona Lisa? Sitting there and smiling lightly with your hands crossed? Yeah, maybe that’s cool if you’re a loser.

When the class began, I broke out every yoga position I knew. When the time came for a single 20-minute long pose I threw up my arms like the angel of victory. And there is an immense peacefulness to that – it is incredibly meditative to focus only on holding your body in place. I felt purposeful again. I wasn’t doing anything, particularly, other than being there, but the students did need me to be there. And when the class ended, everyone said thank you. It felt amazing to be good at something, even if the something in question wasn’t all that much.

However, what I learned after a few weeks was that the angel of victory must have had absolutely no feeling in her limbs. Holding your arms up for 20-minute sessions over and over? That hurts. I cramped everywhere. One of the retirees in class wanted to talk about his bad back? Oh, I could commiserate about bad backs. I could win that discussion.

I opted for more and more reclining poses. I became demanding over pillows. I subtly nudged myself into positions where I had a book in front of me, turning the pages with one finger. I didn’t just want to lie there. I wanted to read.

“You like Fragonard?” I would ask the instructor, desperately clutching my copy of Sloane Crosley's book "I Was Told There'd Be Cake," in what I approximated as the same pose as the girl in the artist's portrait "The Reader." “What’s that good Fragonard painting? You know, the one everyone wishes they could paint some variation of?” I managed to read my book for some poses -- until one instructor thought I meant Fragonard’s more famous painting, "The Swing," and wondered if I wanted a swing moved into the room.

When another instructor asked what music I’d like played -- a very generous offer on his part -- I initially tried to select tunes I thought would be fun for everyone. First I chose the Beatles. I didn’t want to offend. But over time, I became bolder. Frank Sinatra. Then, drunk on my own power: the Smiths. The Mountain Goats, but only the great songs. Choices got weird. Ruth Etting! Ivor Novello! The original 1961 cast recording of "Camelot"! (People were surprisingly OK with that one).

As time passed, I began to see models in art books not for their beauty, but for the poses they held. I flipped to a photo of “Olympia” and thought, “Oh, lady, way to choose a pose that is not as painful as it could be.” When I looked at “Luxe, Calme et Volupte,” all I could think was, “How long do you think that poor girl had to hold her arms over her head that way? I hope they had a phonograph.”

Being an art model began to feel less like getting to sleep in on a Saturday morning, and more like being sent to bed early as a punishment. It occurred to me that the paintings I loved seemed so peaceful because they captured only a moment in those subject’s lives. That a second afterward, Olympia got up and went to her lover or put her flowers in water or did whatever she did that day. The bathers in “Luxe, Calme et Volupte” got on their boat and sailed back to their real life. The moment captured in those pictures was beautiful, but fleeting. The day finally came when I thought, “Sitting here with my legs crossed for the next five hours is literally going to drive me insane.”

And so I branched out into jobs that required being mobile. Then ones that required a level of planning that would elude a pomegranate. And, eventually, I transitioned into a job I love, with health benefits, and an office I go to each morning, scurrying down the street, clutching a skinny caramel macchiato (they’re good).

But sometimes I miss those months when I seemed frozen in time. If they weren’t voluptuous, they were calm. Then I remember all the men who told me that I looked like whatever girl they had seen naked 50 years ago. These days, I think all they were really saying was they’d gone out into the world and lived. After a while, so did I.

Shares