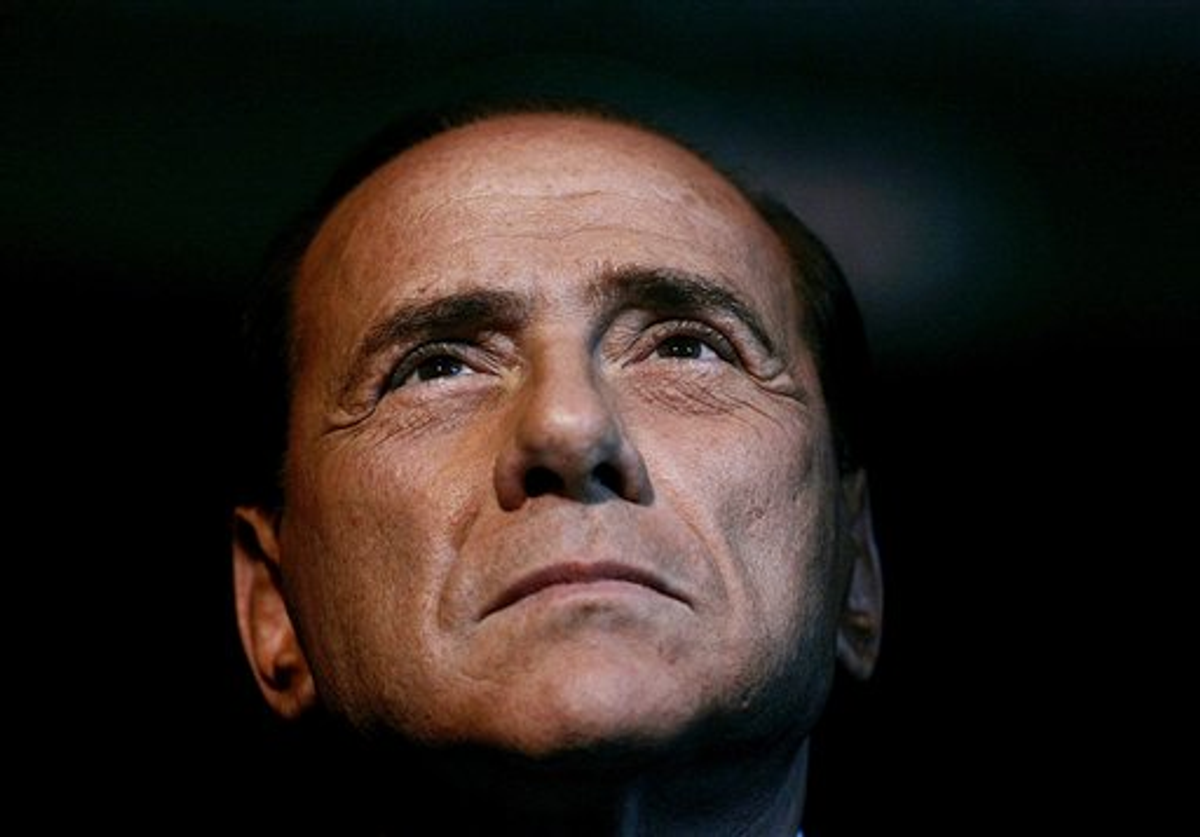

ROME, Italy – Despite Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi's announcement Tuesday that he will step down, it’s still anyone’s guess how long he will manage to hold on to his job. But one thing is clear: after 17 years in Italy’s political spotlight, Berlusconi’s often mesmerizing political drama has reached its last act. What follows may be a very painful chapter in Italy's history.

On Tuesday, the 75-year-old leader best known for verbal gaffes, “bunga bunga” sex parties, and a steady stream of legal troubles, lost a key parliamentary vote. After several hours of reflection and meeting with his children and close advisors, Berlusconi told Italian President Giorgio Napolitano he would relinquish his power after the latest Italian emergency austerity package is approved by parliament.

On Tuesday, the 75-year-old leader best known for verbal gaffes, “bunga bunga” sex parties, and a steady stream of legal troubles, lost a key parliamentary vote. After several hours of reflection and meeting with his children and close advisors, Berlusconi told Italian President Giorgio Napolitano he would relinquish his power after the latest Italian emergency austerity package is approved by parliament.

More than anything, Italy is in dire need of fiscal austerity: the country’s public debt has reached $2.6 trillion, the equivalent to 120 percent of the country’s gross domestic product.

In a dramatic development that increases the pressure on the euro zone, fears that Italy could default on its debt drove yields on the country's benchmark ten-year bonds over 7 percent on Wednesday. That's the threshold that sent Ireland, Portugal and Greece scurrying for bailout funds earlier this year.

The stakes are far higher with Italy, which has an economy nearly three times larger than Ireland, Portugal and Greece combined. If Italy goes bankrupt, it is unlikely that the euro currency would survive.

Analysts say that the Italian austerity package is far too small to do much good. And the fact that Berlusconi has tied his political fate to the passage of the package may assure that it will become bogged down in political bickering that may mean Berlusconi’s remaining tenure will be measured in weeks or perhaps months, rather than days.

Once he is gone, President Napolitano will have several options. He could ask some figure to try to cobble together a majority government among the sitting parliament, or he could call for new elections to shuffle the deck. In the meantime, Berlusconi could remain prime minister with restricted powers as an overseer to a caretaker government, or he could be replaced by an appointed figure who would help oversee fiscal and political reform plans before elections take place.

Two names that have been floated as possible appointees to head a temporary technical government are Angelino Alfano, the head of Berlusconi’s Polo di Liberta (People of Liberty) political party, and the highly respected Mario Monti, the former European Competition Commissioner who has in the past refused joining governments from both the left and right.

Whoever ends up filling Berlusconi’s shoes, he will face severe economic problems. Markets had mixed reactions once speculation began that Berlusconi could be on the way out. The Italian Stock Exchange in Milan closed in positive territory on Monday and Tuesday and was trading higher early Wednesday before plunging on the news that a key trading house was increasing margin requirements on the country's debt.

No matter what happens in the short term, Italy remains the sick man of Europe: youth unemployment surpassed 30 percent for the first time this summer; the country suffers from a bloated public sector in which most jobs are handed out based on personal connections rather than merit; there is a steady exodus of skilled and highly educated Italians who opt to work outside the country; the Italian Treasury suffers from massive levels of tax evasion; and the country has the most expensive pension system in the world in per-capita terms.

It is likely that the new leader will lack the gravitas to tackle these problems, at least at first. Berlusconi was skilled at cutting down rivals at the knees before they achieved support levels or visibility to challenge him, leaving a field of under-experienced and flawed candidates to fill the void Berlusconi leaves.

And it is best not to forget that Berlusconi will remain a key force in Italy. Being prime minister is, after all, his second vocation, and only one of his levers of power. His day job is as Europe’s richest media tycoon, where his holdings include three national television networks, a leading daily newspaper, a major news magazine, a large film production and distribution company, and Italy’s largest advertising media buyer.

Unless he has a say in who takes his place, he will likely use his media empire to make life difficult for Italy’s first post-Berlusconi leader.

Shares